* In the postwar period, Great Britain built not one but three long-range jet bombers -- the "Valiant", "Victor", and "Vulcan" -- as the backbone of that nation's nuclear deterrence force. The first of these "V-bombers" was the Vickers Valiant, which served through most of the 1950s and into the early 1960s. This document provides a history and description of the Valiant. A list of illustration credits is provided at the end.

* The British Royal Air Force's (RAF) Bomber Command left World War 2 with a policy of using heavy four-piston-engined bombers for massed raids, and remained committed to this policy in the immediate postwar period, adopting the Avro Lincoln, an improved version of the WW2 Lancaster, as their standard bomber. The development of jet aircraft and nuclear weapons soon made this policy obsolete. The future appeared to belong to jet bombers that could fly by themselves at high altitude and speed, without defensive armament, to perform a nuclear strike on a target. To be sure, even at the time there were those who could see that at some time in the future guided missiles would make such aircraft vulnerable, but development of such missiles was proving difficult, and fast and high-flying bombers were likely to serve for years before there was a need for something better.

In any case, massed bombers were unnecessary if a single bomber could destroy an entire city or military installation with a single bomb. It would have to be a large bomber, since the first generation of nuclear weapons were big and heavy. Such a large and advanced bomber would be expensive on a unit basis, but thanks to the awesome power of the "nuke", such aircraft wouldn't need to be built in large quantities. Britain had been economically bled dry by the war, and the potential cost savings were attractive.

The arrival of the Cold War also emphasized to British military planners the need to modernize British forces. Furthermore, Britain's up-and-down relationship with the USA, particularly in the immediate postwar years when American isolationism staged a short-lived comeback, led the British to feel they needed their own strategic nuclear strike force.

After considering various specifications for such an advanced jet bomber in late 1946, in January 1947 the British Air Ministry issued a request for an advanced jet bomber that would be at least the equal of anything the US or the USSR had. The request went to most of England's major aircraft manufacturers.

The request followed the guidelines of the earlier specification "B.35/46", which proposed a "medium-range bomber landplane, capable of carrying one 10,000 pound [4,535 kilogram] bomb to a target 1,500 nautical miles [2,775 kilometers] from a base which may be anywhere in the world." The request also indicated that the fully loaded weight of the aircraft not exceed 45,350 kilograms (100,000 pounds), though that would be adjusted upward in practice; that the bomber have a cruise speed of 925 KPH (500 knots); and that it have a service ceiling of 15,240 meters (50,000 feet).

* Since the requirements for B.35/46 were stiff, the Air Ministry also issued "B.14/46", a requirement for a more conservative jet bomber that would provide "insurance" in case the advanced B.35/46 effort ran into trouble. In August 1947, a contract was awarded to Short Brothers for the "SA.4" four-engine jet bomber, with the contract specifying construction of two flying prototypes and a static-test machine.

The Shorts SA.4 was, by intent, a conservative design, basically a jet-powered version of a World War II style bomber with conventional tail assembly and straight wings, though the wings did have leading-edge sweep. The only particularly unusual feature of the SA.4 was that the four Rolls-Royce Avon engines were fitted in nacelles mounted in the midwing, with two engines in each nacelle mounted in a top-and-bottom fashion.

The "Sperrin", as it was called, was to have a crew of five, including pilot, copilot, bombardier, navigator, and radio operator, in pressurized accommodations. Only the pilot had an ejection seat. The Sperrin had no defensive armament. It was to carry radios, navigation avionics, and bombing radar, and space was set aside for defensive electronic countermeasures.

The Sperrin was of conventional monocoque construction and built largely of aircraft aluminum alloys. It featured tricycle undercarriage, with twin-wheel nose gear retracting backward and four-wheel main gear, arranged as 2x2 bogies, retracting from the wings towards the fuselage. A dual-parachute brake chute system was also fitted.

SHORT SA.4 SPERRIN: _____________________ _________________ _______________________ spec metric english _____________________ _________________ _______________________ wingspan 33.2 meters 109 feet wing area 176.2 sq_meters 1,897 sq_feet length 31.14 meters 102 feet 2 inches height 8.69 meters 28 feet 6 inches empty weight 32,660 kilograms 72,000 pounds MTO weight 52,165 kilograms 115,000 pounds max speed at altitude 912 KPH 567 MPH / 492 KT service ceiling 13,715 meters 45,000 feet range 5,150 kilometers 3,200 MI / 2,780 NMI _____________________ _________________ _______________________

The first prototype performed its initial flight on 10 August 1951, with Shorts chief test pilot Tom Brooke-Smith at the controls. It was fitted with Avon RA.2 turbojets with 26.6 kN (2,720 kgp / 6,000 lbf) thrust each. In March 1950, well before the initial flight, the Air Ministry had decided that the Sperrin wouldn't be put into production, but work on the two prototypes was allowed to continue. The second prototype performed its first flight on 12 August 1952. It was fitted with Avon RA.3 turbojets with 28.1 kN (2,950 kgp / 6,500 lbf) thrust each.

The two Sperrin prototypes were used in a variety of trials through the 1950s, including tests for:

Both Sperrin prototypes were scrapped in the late 1950s. Shorts also proposed a design based on the SA.4 for the more advanced B.35/46 specification, the "SB.1", featuring a fuselage like that of the SA.4 but with a "tailless" configuration, using the company's "aero-isoclinic" scheme. The outer sections of the wings were pivoted, allowing them to maintain the same incidence even as the wing flexed. The pivoted wingtips acted as both elevators, rotating together to control pitch, and ailerons, rotating in reverse direction to control roll. The SB.1 featured the engine arrangement of the SA.4, with twin Avons in nacelles arranged top and bottom of the wing, but with a fifth Avon added in the rear of the fuselage, with an intake on top.

The SB.1 was too daring for the Air Ministry, though the aero-isoclinic wing was tested on a small demonstrator, the "SB.4 Sherpa", in the early 1950s, with surprisingly good results. However, the aero-isoclinic configuration didn't really seem to have any major advantages over more conventional configurations, and that line of investigation proved a dead end. The Sherpa name would be recycled later for the Shorts 330 / C-23 light twin-engine light transport.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Sperrin was never anything more than a footnote to Britain's strategic bomber development effort. Other work would achieve much more significant and impressive results.

Handley-Page and Avro came up with very advanced designs for the bomber competition, which would become the Victor and the Vulcan respectively, and the Air Staff decided to award contracts to both companies, again as a form of insurance.

While Vickers-Armstrong's submission was originally rejected as too conservative, Vickers' chief designer George Edwards energetically lobbied the Air Ministry and made changes to meet their concerns. Edwards managed to sell the Vickers design to the Air Ministry on the basis that it would be available much sooner than the competition, going so far as to promise delivery of a prototype in 1951 and production aircraft in 1953. The Vickers bomber would be useful as a "stopgap" until the more advanced bombers were available -- apparently, the Air Ministry didn't think there could be too much insurance.

Although the idea of developing, much less fielding as turned out to be the case, three entirely different large aircraft in response to a single request is unthinkable now, aircraft were less sophisticated in those days, development was not generally so troublesome and certainly much less expensive. One aviation writer observed, probably with a certain amount of exaggeration, that it cost less to develop a combat aircraft at the dawn of the jet age than it would to produce the manuals for a modern counterpart.

In April 1948, the Air Staff issued a specification with the designation "B.9/48" written around the Vickers design, which was given the company designation of "Type 660". Two prototypes of the aircraft were ordered in February 1949. The first was to be fitted with four Rolls-Royce RA.3 Avon axial-flow turbojet engines, while the second was to be fitted with four Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire turbojets and given the company designation of "Type 667".

The Type 660 looked very promising and led to the Air Ministry's decision to not put the Sperrin into production. The first Type 660 prototype, gleaming in natural-metal finish, took to the air on 18 May 1951, as George Edwards had promised, and in fact beat the first Shorts Sperrin into the air by three months. It had only been 27 months since issue of the contract. The pilot was Jeff "Mutt" Summers, who had also been the original test pilot on the Supermarine Spitfire and wanted to add another "first" to his record before he retired. His co-pilot on the first flight was Gabe "Jock" Bryce, who replaced Summers after he retired.

The Vickers Type 660 was given the official name of "Valiant" the next month, recycling the name from the Vickers Type 131 general-purpose biplane of 1931. RAF bombers had been traditionally named after cities, for example "Lancaster", "Halifax", and "Canberra", but the new aircraft technology seemed to suggest a break from tradition, and the name "Valiant" was selected by a survey of Vickers employees.

The first Valiant prototype was lost due to an in-flight engine fire in January 1952, all the crew escaping safely except for the co-pilot, who struck the tail after ejecting and was killed. After modifications to the fuel system to eliminate the fire hazard, the second prototype first flew on 11 April 1952. It was fitted with RA.7 Avon engines with 33.4 kN (3,400 kgp / 7,500 lbf) thrust each, instead of the Sapphires originally planned. It originally flew in natural metal finish but was later given an overall silver paint job. The loss of the initial prototype did not seriously compromise schedule, since the accident occurred so late in the flight test program.

An initial order for a first production batch of "Valiant Bomber Mark 1 (B.1)" aircraft had already been placed in January 1951. The first production aircraft flew in December 1953, again more or less on the schedule Edwards had promised, and was delivered to the RAF in January 1955. Britain's "V-bomber" force, as it had been nicknamed in October 1952, was now in operation. The Victor and Vulcan would follow.

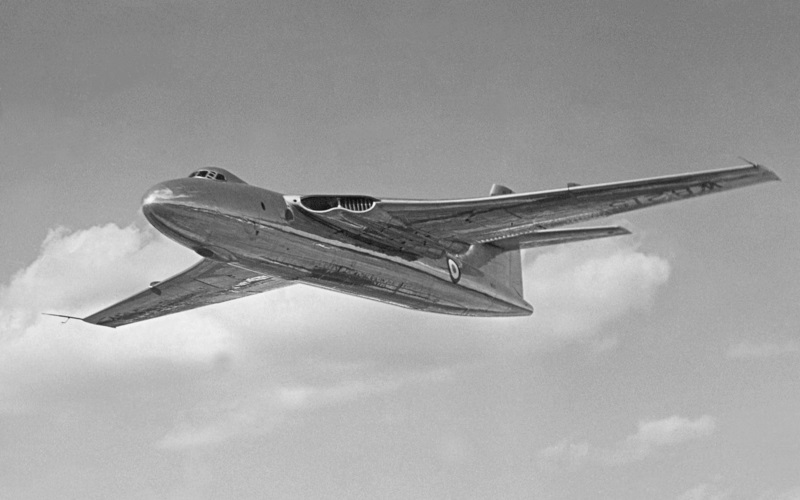

BACK_TO_TOP* The Valiant prototype was a relatively conservative and conventional design, with a shoulder-mounted wing and twin Avon RA.3 turbojets, with 28.9 kN (2,950 kgp / 6,500 lbf) thrust each, in each wingroot for a total of four engines. The engine bays were designed to permit the use of Sapphire engines as a backup plan. The overall impression of the design was of a plain and clean aircraft, appealing in its simplicity as were many early jet aircraft. George Edwards described it appropriately as an "unfunny" machine.

The wing's good size allowed it to have a ratio of wing thickness to chord of 12% and still accommodate the Avon engines within the wing roots. This engine fit contributed to the aircraft's aerodynamic cleanliness, at the expense of making engine access for maintenance and repair more troublesome; and increasing the risk of "fratricide", with the failure of one engine possibly contributing to the failure of its partner.

The wing had a "compound sweep" configuration, devised by Vickers aerodynamicist Elfyn Richards, with a large 45-degree angle of sweepback in the inner third of the wings and a shallow angle of about 24 degrees sweep outboard. The compound sweep was a good compromise between aerodynamic efficiency and aircraft balance. The wing featured large flaps, scalloped out around the engine exhausts, for better take-off and landing performance, and had airbrakes above the wings.

The engine inlets were long rectangular slots in the first prototype, but following Valiants featured double-oval ("spectacle") shaped inlets to permit greater airflow for more powerful Avon engine variants. The jet exhausts emerged from fairings above the trailing edge of the wings. The tail was sweptback, and the tailplane was mounted well up the tailfin to keep it out of the engine exhaust and so improve controllability.

The wing loading was relatively low, reducing take-off run and increasing range, and the Valiant was also fitted with double slotted flaps to shorten take-offs. The aircraft featured tricycle landing gear, with twin-wheel nosegear retracting backward, and tandem-wheel main gear retracting outward into the wing. Most of the aircraft's systems were electric, an innovative scheme at the time, with the power system based on 112 volts DC. The brakes and steering gear were hydraulic, but the hydraulic pumps were electrically driven.

The Valiant was built around a massive "backbone" beam that supported the wing spars and the weight of bombs in the long bomb bay. The crew, housed in a pressurized "egg", consisted of pilot, copilot, two navigators, and an electronics operator. The crew got in and out of the cockpit through an upward-hinged oval door on the left side. Only the pilot and copilot had ejection seats, which fired upward; the other three crew members had to jump out of the bomber on their own. The Victor and Vulcan had the same general crew and escape system arrangement.

The Air Ministry had originally envisioned that the entire nose of all the V-bombers would be discarded as an escape system, but this proved impractical -- trying to paradrop such a heavy item and not killing the crew on impact was too difficult. An ejection system was in fact designed later for the other three crew members: they would sit side-by-side, facing backwards, with the center crewman ejecting first through a roof hatch, then each of the other seats shunted to that position and ejected in turn. Experiments were conducted in 1960 using a Valiant and firing a single seat as a demonstration, but that was as far as it went. The scheme wasn't implemented, since it would have required major alterations to the aircraft.

In hindsight, the good safety record of the Valiant and the other V-bombers made it clear this would not have been a good use of money; the pilot and co-pilot would be the last out in any case, not ejecting until the other crew had escaped, and since the ejection seats of the era didn't have low-altitude capability, they wouldn't make much difference in a low-level accident.

The Valiant B.1 could carry a single 4,500-kilogram (10,000-pound) nuclear weapon or up to 21 450-kilogram (1,000-pound) bombs in its bomb bay. Landing gear clearance was on the short side, so the bomb bay doors retracted up into the fuselage to facilitate bomb loading. Large external tanks, one carried under each wing and with a capacity of 7,500 liters (1,979 US gallons), could be fitted to extend range. There was work done on pods that could be fitted in place of the tanks to carry additional bombs, but that effort was canceled. The aircraft had no defensive armament, though a tail turret had been considered.

The B.1 was fitted with a sophisticated (for the time) "Navigation / Bombing System (NBS)", built around the H2S Mark 9a Yellow Aster radar. Development of the NBS was protracted, and many Valiants weren't fitted with it until well after they had gone into service. The navigation system also included a Green Satin Doppler navigation radar and a Gee-H radio location system. There was a blister under the nose to allow the bombardier to lie prone and pinpoint a target through an optical sight.

Initial Valiant production aircraft featured four Rolls-Royce Avon 201 turbojet engines, with 42.3 kN (4,310 kgp / 9,500 lbf) thrust each. Trials were performed with De Havilland Super Sprite liquid rocket booster engines, one attached under each engine pair, with the boosters dropped by parachute after take-off. The rocket boosters were actually qualified for service but never used, since the Avon RA.24 engines turned out to provide all the take-off power needed.

___________________________________________________________________

VICKERS VALIANT B.1:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

34.8 meters (114 feet 4 inches)

wing area:

219.43 sq_meters (2,362 sq_feet)

length:

33.0 meters (108 feet 3 inches)

height:

9.8 meters (32 feet 2 inches)

empty weight:

34,400 kilograms (75,880 pounds)

max loaded weight:

79,400 kilograms (175,000 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

912 KPH (567 MPH / 493 KT)

service ceiling:

16,460 meters (54,000 feet)

range with tanks:

7,245 kilometers (4,500 MI / 3,915 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

* All Valiant production ended in August 1957. Including three prototypes, a total of 107 Valiants was built, including:

Eight Valiants, including one used for trials, were modified for the "radio countermeasures (RCM)" role, where RCM was what is now called "electronic countermeasures (ECM)". These aircraft were ultimately fitted with AN/APT-16A and AN/ALT-7 jamming transmitters; Airborne Cigar and Carpet jammers; AN/APR-4 and AN/APR-9 signals intercept receivers; and chaff dispensers.

Originally, Valiants were finished in silver, but once equipped with nuclear weapons they were painted in "anti-flash" white to reflect the glare of a nuclear blast. However, the RAF roundels were left in solid red-white-blue. It was later realized that the insignia might be permanently burned into an aircraft by a blast; in the other V-bombers, the roundel became faded pink-white-violet, but the faded insignia was not generally applied to the Valiant fleet. Some sources claim that it was applied to some of the Valiants used in nuclear test drops.

* Of the three prototypes, one was for an advanced variant, the "Valiant B.2", with this prototype known as the "Black Bomber" since it was painted gloss black. It was intended as a "pathfinder", penetrating to a target area at low level and marking it with flares for a follow-up strike by other bombers. The Air Ministry ordered 17 B.2s, including two prototypes and 15 operational aircraft, in April 1952. Only one was actually completed, flying for the first time in September 1953.

For center of gravity reasons, the B.2 featured a fuselage stretch forward of the wings for a total length of 34.8 meters (114 feet), in contrast to a length of 33 meters (108 feet 3 inches) for the Valiant B.1. Since the B.2 was intended for low-level operations, the wing was strengthened, which required rethinking the main landing gear. The B.2's main landing gear, featuring four wheels instead of two, retracted backwards into fairings called "speed pods" in the wings. This arrangement was similar to that used in a number of Soviet Tupolev aircraft, such as the Tu-16 "Badger".

The Air Ministry eventually realized that target marking was an outdated concept. Although the Valiant B.2's low-level capabilities would later prove to be highly desireable, the B.2 program was canceled in 1955. The B.2 prototype was used for tests for a few years, including evaluation of the tanker system, then incrementally destroyed in the humiliating role of "ballistic target" for ground gunnery.

* Vickers proposed a "Valiant B.3" in 1952, featuring a new wing with greater sweepback and better performance, but the RAF was focusing on the other V-bombers and the Mark 3 never happened. Vickers also considered an air transport / tanker version of the Valiant, with a low mounted wing, wingspan increased to 42.7 meters (140 feet) from 34.8 meters (114 feet 4 inches), fuselage lengthened to 44.5 meters (146 feet), and more powerful Rolls-Royce Conway engines. It looked something like a de Havilland Comet airliner with Valiant wings, but was to be larger and faster than the Comet.

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) ordered construction of a prototype of the "Vickers Type 1000 (V.1000)", as it was designated, in October 1952, with construction beginning in February 1953. The V.1000 was to be built in two versions, the "V.1001" for the RAF and the "V.1002" or "VC-7" for civilian use. In June 1954, the MoS ordered six production V.1001s, to be fitted with 120 rearward-facing passenger seats, and the British Overseas Aircraft Corporation (BOAC) was interested in the VC.7 version.

However, the government canceled the V.1001 order on 11 November 1955. There was apparently some notion in the government that BOAC would keep the project alive anyway, but BOAC was unwilling. Vickers gave up the project at the end of November and scrapped the V.1000 prototype, only a few months before its scheduled first flight. Some of the thinking that went into the V.1000 did emerge eventually in the Vickers VC.10 airliner / tanker, a fine and elegant aircraft that provided long and useful service, but was only built in modest numbers.

BACK_TO_TOP* Since the Valiant was an entirely new class of aircraft for the RAF, the 232 Operational Conversion Unit was established at RAF Gaydon to help get the bomber into service. The first operational RAF unit to be equipped with the Valiant was 138 Squadron, also at RAF Gaydon at first, though it later moved to RAF Wittering. At its peak, the Valiant equipped eight operational squadrons, including one PR squadron (Number 543) and seven "Main Bomber Force (MBF)" squadrons (Numbers 7, 49, 90, 138, 148, 207, & 214). It partly equipped an RCM squadron (Number 18), which also operated the English Electric Canberra and other aircraft.

The Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to see real combat, during the Anglo-French-Israeli Suez intervention in October and November 1956. Under Operation MUSKETEER, as the operation was named in honor of its three-party nature, Valiants operating from the airfield at Luqa on Malta pounded Egyptian targets with high-explosive bombs. It was the last time any of the V-bombers flew an actual strike mission, until Avro Vulcans pounded targets in the Falkland Islands during the Falklands Crisis in 1982.

Although Egyptians did not oppose the attacks and there were no Valiant combat losses, the results of the raids were disappointing. Their primary targets were seven Egyptian airfields, and though the Valiants dropped a total of 856 tonnes (942 tons) of bombs, only three of the seven airfields were seriously damaged. The Valiant had just entered operational service and the crews were inexperienced with the type -- some sources claim these machines still hadn't been fitted with radar -- which explains the poor results. The Valiant wouldn't get a chance to prove it could do better either, since it never dropped a bomb in anger again.

A Valiant B.1 of Number 49 Squadron was the first RAF aircraft to drop a British operational atomic bomb, performing a test drop of a downrated "Blue Danube" weapon on Maralinga, South Australia, on 11 October 1956. A few months later, a 49 Squadron Valiant B(K).1 dropped the first British hydrogen bomb, the "Green Granite Small", over the Pacific as part of Operation GRAPPLE. The blast was impressive but not a complete success, the measured yield being less than a third of the maximum expected. The British still had a bit more work to do on their fusion weapons.

The GRAPPLE series of tests continued into 1958, and the first really satisfactory drop occurred in April 1958, with a Green Granite Large bomb exploding with ten times the yield of the original Green Granite Small. Further tests followed, but were finally terminated in November 1958, when the British government decided they would perform no more nuclear test blasts, eventually renouncing them completely. The Valiant, incidentally, was the only one of the V-bomber fleet to ever drop live nuclear weapons.

The Valiants of the MBF carried either British-built weapons such as the Blue Danube, its improved "Yellow Sun" replacement, and the "Red Beard" tactical nuclear weapon, or US-supplied weapons under a "dual-key" arrangement -- though that arrangement made use of the American weapons very clumsy. From the late 1950s, Valiants were increasingly fitted with nose refueling probes, with the new Valiant tanker force greatly extending the operation range of the fleet.

Some sources claim the Valiant carried the Blue Steel nuclear-tipped standoff missile that was carried by the Victor and Vulcan, but in fact the Valiant was only used to test various powered and unpowered models and prototypes of the weapon. Blue Steel didn't go into service until 1963, after the Valiant had been retired from the strategic bombing role. Once the other V-bombers were in full service, in 1962 the Valiant MBF force was dissolved, with three of the squadrons (Numbers 47, 148, & 207) re-roled to support NATO in "Tactical Bomber Force (TBF)" operations, operating at low level to deal with ever-improving Soviet defenses. Two squadrons (Numbers 90 & 214) were re-roled to Valiant tanker operations, while Number 543 Squadron continued in the strategic photo-reconnaissance role.

The Valiant TBF was under overall control of USAF SAC Europe, and the Valiants carried two US-provided nuclear weapons each -- originally Mark 28s, quickly transitioning to the Mark 43, a parachute-retarded weapon designed specifically for low-level drop. Since these Valiants were under American command, use of the American munitions was not the problem that it had been for the strategic role. The Valiants were given a new camouflage paint job, with a disruptive pattern of gray and green above, the white retained below.

They only flew in the new color scheme for a short time, since low-level operations proved too much for the Valiant. Following a series of accidents, inspections showed that the main wing spars of the Valiants in operation were suffering from excessive fatigue. There was hope that the tankers, which didn't generally operate at low level, might be in better condition, but that didn't prove to be the case. Replacing the wing spars was deemed too expensive for an aircraft that was going out of service in 1968 anyway, and had been built as an interim solution to begin with. The Valiant force was grounded, to be removed from service in 1965.

Although the Valiant tanker had left something to be desired -- with only a single refueling point, a relatively limited fuel capacity of 20,400 kilograms (45,000 pounds), and inadequate performance at high weights -- the grounding of the Valiants put the RAF in a bind, forcing the acceleration of work to convert Victors into tankers.

One Valiant was re-sparred before the decision was made to ground the fleet, and this aircraft was used in trials for a few years. It performed its last flight in June 1968, as part of an airshow tribute to the 50th anniversary of the RAF.

* The Valiant was a competent and effective aircraft, and was particularly noteworthy for the speed with which it was designed and introduced, with remarkably few changes between the initial prototype and production machines. In fact, some aviation observers suggest that if the Valiant B.2 had been adopted the Victor and Vulcan would have been redundant, and Britain could have had every bit as effective a V-bomber force at lower cost -- though one that wouldn't have been nearly as distinguished.

Only one complete Valiant survives today, on static display at the RAF Museum at Cosford. It was the first of the Valiants to drop an H-bomb under GRAPPLE, and was felt to have special significance.

BACK_TO_TOP* One Valiant was used in trials in 1963 and 1964 for the Rolls-Royce Pegasus vectored-thrust turbofan, which would ultimately power the Harrier jump-jet. The engine was crammed into the bomb bay and protruded below the fuselage, providing minimal ground clearance. 50 test flights were performed.

Vickers designers considered a few exotic derivatives of the Valiant. A "low-level Valiant" design featured a fuselage stretch, short wings, and additional fuel carriage. A "supersonic Valiant" design featured a highly swept wing, four afterburning Conway turbojets, a swept tee tail, and improved streamlining. The supersonic Valiant would have had a maximum speed of Mach 1.4, but these two designs were simply casual proposals. They never went beyond concept sketches and rough design calculations.

* While Vickers worked on the Valiant, the company was also considering a much more advanced design that could have resulted in yet another "V-bomber". In the early 1950s, the company's Barnes Wallis, who had developed the well-known "dambuster" bomb during World War II, was considering the possibility of "variable geometry" AKA "swing wings". Wallis came up with a general design that featured a fuselage in the shape of a slender triangle, with long wings on the back vertices that could be pivoted forward and aft. There were twin engines, top and bottom, near each wingtip, that pivoted along with the wing to remain pointing forward. Large models of the "Swallow", as it was named, with an extended span of 9.1 meters (30 feet), were tested in a wind tunnel, while flying models were tested using rocket boosters for propulsion.

Wallis wanted to move on to a piloted development aircraft, the "Research Swallow", which was to have a span of 22.9 meters (75 feet) with wings extended and 9.35 meters (31 feet) when fully swept; it was to be powered by four Bristol afterburning turbojets, giving it a top speed in excess of Mach 2. The Research Swallow was seen as the basis for a one or two seat combat aircraft, most prominently an interceptor armed with air-to-air missiles. Wallis envisioned a range of larger versions, such as a Swallow "V-bomber" and a supersonic transport.

Alas, the late 1950s were a dismal time for the British aviation industry, with many promising development programs shut down. The Research Swallow was never built; there were discussions with the Americans on further consideration of the design, with the US National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) performing advanced studies on the concept. By mid-1959, NASA had concluded that the Swallow itself was aerodynamically dubious -- but the variable geometry concept was seen as very promising, with further work in the USA leading to the world's first operational variable geometry aircraft, the General Dynamics F-111.

BACK_TO_TOP* Some years back, after the release of the initial version of this document, I was contacted by an Australian who told me he had been a test copilot on a Valiant when the wing spar broke. The wing didn't tear off, and the aircraft managed to get back down to the ground in one piece. Some more time after that, I was contacted by a genial Briton living in the US who had also flown the Valiant. It turned out he was the pilot on the same flight where the wing spar broke. "It's a small world, but I wouldn't want to paint it."

* Sources include:

Some comments were also obtained from Damien Burke's THUNDER & LIGHTNINGS page in the UK.

* Illustrations details:

* Revision history:

v1.0 / 01 sep 00 v1.1.0 / 01 apr 03 / Review & polish. v1.1.1 / 01 apr 05 / Review & polish. v1.2.0 / 01 feb 06 / Added unbuilt variants. v2.0.0 / 01 feb 07 / General upgrade. v2.0.1 / 01 feb 09 / Review & polish. v2.1.0 / 01 dec 10 / Comments on Swallow. v2.1.1 / 01 nov 12 / Review & polish. v2.1.2 / 01 oct 14 / Review & polish. v2.1.3 / 01 sep 16 / Review & polish. v2.1.4 / 01 aug 18 / Review & polish. v2.2.0 / 01 sep 20 / Illustrations update. v2.3.0 / 01 dec 21 / Review & polish. v2.3.1 / 01 nov 23 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP