* Using the A-12 as a basis, Lockheed developed a more capable successor for the US Air Force, which emerged as the "SR-71 Blackbird" AKA "Habu". It had a much longer career, proving a useful asset up to its -- some thought premature -- retirement. Lockheed also developed a Mach 3 drone, the "D-21", based on SR-71 technology, but it never saw real operational service.

* While the CIA was trying to get the A-12 up to speed, the USAF was working on a competitor. In 1962, Kelly Johnson had offered proposals to the Air Force for a version of the A-12 modified to Air Force requirements, with the designation of "R-12". He also pushed a "reconnaissance-strike" version of the same aircraft, designated the "RS-12".

An initial contract for the R-12 was awarded to Lockheed in 1963, with the aircraft given the USAF designation of "SR-71", where "SR" stood for "strategic reconnaissance". The USAF never bit on the strike concept. President Lyndon Johnson announced the program to the world in 1964. There is some confused and confusing story that the machine was supposed to be designated the "RS-71", but Johnson got the designation wrong. The matter is too trivial to investigate.

Initial flight of the SR-71 was on 22 December 1964, with test pilot Bob Gilliland at the controls. The type would be given the official name of "Blackbird". Initial deployment was in 1965, to the new 4200th -- later the 9th -- Strategic Reconnaissance Wing at Beale Air Force Base in California. Beale would become the SR-71's permanent home, though there would be deployments elsewhere. The SR-71s were flown by two of the 9th SRW's squadrons: the 1st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron and the 99th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron. The 99th SRS would give up its SR-71s in 1971, with the 1st SRS continuing to fly the Blackbird.

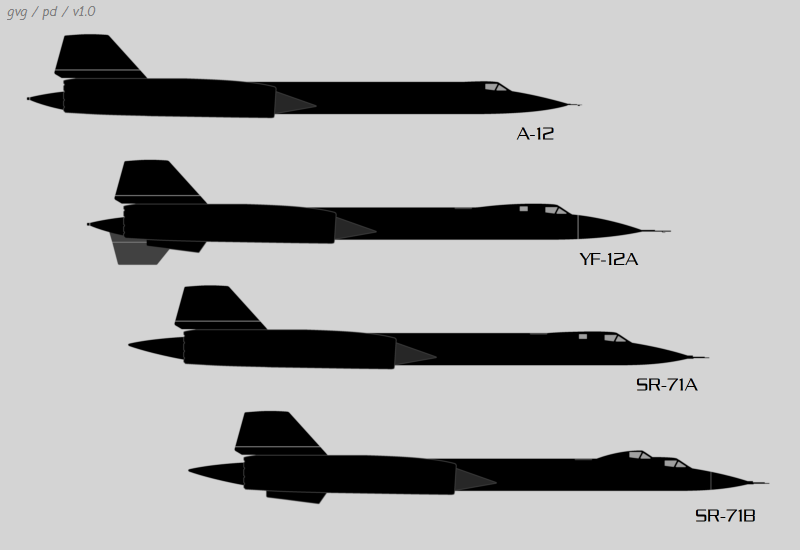

* To a novice, the A-12 and SR-71 looked much alike, but their forward fuselages were distinctly different: the A-12 was a single-seater, while the SR-71 was a two-seater like the YF-12A, with the second seat occupied by a "reconnaissance systems operator (RSO)". The SR-71 was also about 1.9 meters (6 feet) longer -- not just because of the modified forward fuselage, but also because it had a tailcone -- and had a loaded weight about 6,800 kilograms (15,000 pounds) greater.

The greater weight was in part because the SR-71 had more fuel capacity, with tanks in the wings inboard of the engines, total capacity being raised to 46,254 liters (12,219 US gallons). With the greater weight, the SR-71 was marginally slower than the A-12. The nose chines were more elliptical, and the nose was replaceable, variations including:

The SR-71 didn't have a Q-bay, instead having a set of ten separate bays for reconnaissance gear and electronics -- two small bays associated with the cockpit, and four bays on each side of the fuselage, running back to the wings.

The SR-71's payload bay arrangement was much more flexible than that of the A-12, but the SR-71 couldn't carry payloads as bulky as those of the A-12. Cameras included "objective operational cameras (OOC)" for survey work, and "technical objective cameras (TEOC)" for close-up work. The TEOC cameras had to have "folded optics" to fit into the bays; the A-12, less cramped for space, had superior cameras early on, though the SR-71's cameras were progressively improved.

Unlike the A-12, the SR-71 carried other payloads besides cameras; no doubt, the diversity of payloads is why the SR-71 included an RSO. Along with the SLAR / ASARS payload in the nose, the SR-71 could carry signals intelligence (SIGINT) payloads of various sorts. They were typically electronic intelligence (ELINT) systems, used to characterize radar emitters and such, since the high speed of the Blackbird made communications intelligence (COMINT) gathering impractical. COMINT was better performed by slower aircraft with long endurance.

_____________________________________________________________________

LOCKHEED SR-71 BLACKBIRD:

_____________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

16.94 meters (55 feet 7 inches)

wing area:

166.8 sq_meters (1,795 sq_feet)

length:

32.74 meters (107 feet 5 inches)

height:

5.64 meters (18 feet 6 inches)

empty weight:

30,615 kilograms (67,500 pounds)

MTO weight:

52,255 kilograms (140,000 pounds)

maximum speed:

3,555 KPH (2,210 MPH / 1,920 KT)

service ceiling:

> 25,900 meters (> 85,000 feet)

range:

5,230 kilometers (3,250 miles / 2,825 NMI)

_____________________________________________________________________

Cockpit layout had some broad similarities to that of the A-12, but also major differences. The front cockpit didn't have a driftsight, but did have a periscope that could be used to check for engine fires, or to see if the Blackbird was leaving a contrail. The rear cockpit did have a "viewscope" that was much like the driftsight, allowing the RSO to check below the aircraft. It was eventually upgraded from a periscope to a camera.

Another eventual addition was an artificial horizon, to tell the pilot what the aircraft orientation was, which could be a particular problem in the dark. The artificial horizon was displayed as a line of laser light across the dashboard; if the nose went down, the horizon line went up, and the reverse, while the line tilted when the aircraft did. The RSO, incidentally, did not have rear-cockpit flight controls. However, the RSO was also the navigator, and could plot a course for the autopilot system. On the other side of the same coin, the pilot didn't have direct access to the navigation system. In addition, the RSO supervised the defensive countermeasures systems. The aircrew wore updated David Clark S-1030 pressure suits.

Kelly Johnson persisted in trying to sell the Air Force on a strike version of the SR-71, leading to a proposal designated the "B-71". Sketches show it to have weapons bays for four AGM-69 "Short Range Attack Missiles (SRAM)", which were small solid-fuel nuclear-tipped missiles. The B-71 never happened.

32 SR-71s were built, including 29 operational SR-71As and three trainers, with the last machine off the production line delivered in 1967. Two of the trainers were designated "SR-71B"; after one of them was lost in 1968, the YF-12A that was badly damaged in a landing accident in 1966 was hybridized with a static-test airframe to become the sole "SR-71C", to be known as "The Bastard". It was apparently not all that robust and was disliked.

The trainers, incidentally, not only had a piggyback cockpit arrangement, they also had a fixed ventral fin under the rear of each engine nacelle, as per the YF-12A -- though not the folding centerline ventral fin. Pilots also flew the Northrop T-38 Talon supersonic trainer to maintain their flight proficiency, the T-38 having subsonic handling surprisingly similar to that of the SR-71.

BACK_TO_TOP* In 1968 the SR-71, having replaced the A-12 at Kadena, began overflights of North Vietnam, the first on 21 March 1968. The Blackbird proved very useful in helping deal with the siege of Khe Sanh in 1968, providing high-resolution images of the battleground. The SR-71s would continue the overflights at a rate of about one per week for two years. It typically took about a week to turn the S-71 around for a new flight.

The deployments to Kadena were codenamed GLOWING HEAT, with North Vietnam overflights being codenamed GIANT SCALE; the entire SR-71 effort was codenamed SENIOR CROWN. In 1970, the pace picked up to two sorties a week, to reach several times a week in the last phases of the war. The North Vietnamese fired at least 800 SAMs at SR-71s, and never scratched them -- though two were lost to mechanical failures in the course of GLOWING HEAT.

Following the loss of one of the NASA YF-12As in 1971, an SR-71 was loaned to NASA, being redesignated "YF-12C", it appears as a security measure. The YF-12C flew for NASA until 1978, to then be retired to the Pima Air Museum in Arizona, in Tucson.

The SR-71 kept busy during the 1973 Mideast war, performing nine overflights of the war zone. They had to be conducted from Griffiss AFB in New York state, not Mildenhall in the UK, since the British government didn't want to be seen as in support of the missions. The Blackbirds also had to fly over the Straits of Gibraltar, since European countries didn't want them in their airspace. In 1978, two SR-71 sorties were performed over Cuba, to determine if the Soviets had supplied the Cubans with nuclear-capable MiG-23 strike fighters. They turned out to be MiG-23 interceptors.

In the 1970s, the SR-71 set a number of flight records. On 1 September 1974, an SR-71 piloted by Major James Sullivan and RSO Major Noel Widdifield flew from New York City to London in a staggering 1 hour 55 minutes, at an average speed of 2,909.2 KPH (1,806 MPH). On 13 September, the same machine flew from London to Los Angeles in 3 hours 40 minutes, with an average speed of 2,311.3 KPH (1,435.6 MPH).

On 26 July 1976, pilot Captain Robert Helt and RSO Major Larry Elliot set an absolute altitude record for sustained flight -- as opposed to a zoom climb -- of 25,929 meters (85,069 feet). That same day, pilot Captain Eldon Joersz and RSO Major George Morgan set a short-range dash speed record of 3,529.6 KPH (2,193.2 MPH).

Although Beale AFB was the main home of the SR-71, as mentioned, it operated out of Kadena on Okinawa, with what was ultimately designated "Detachment 1". There, the locals called the sinister-looking machine the "Habu", after a resident poisonous snake; that became the SR-71's nickname, in contrast to its official name of "Blackbird". It also flew out of Mildenhall, with "Detachment 4", while the Habus occasionally operated from other air bases as well, such as Eielson AFB in Alaska.

In the 1970s, interest in adding rear-aspect countermeasures systems to the SR-71 led to the idea of adding an extension to the tail to permit more payload volume. One SR-71A was modified with the "Big Tail" extension, to become the "SR-71(BT)", with its initial flight in the new configuration on 20 December 1974.

The extension was phallic in appearance, likely provoking rude jokes; it was 4.19 meters (13 feet 9 inches) long, and had a volume of 1.39 cubic meters (49 cubic feet). It carried a countermeasures system and an optical bar camera, with other variations in payloads fitted as well. It could shift 8.5 degrees up for take-off, to prevent tail strikes, and back down again on landing, to permit use of the drag chute. While the Big Tail scheme was judged successful, no other SR-71 was fitted with it. Indeed, after the Big Tail evaluation program was complete, the SR-71(BT) was parked, to be ignominiously used as a spares hulk.

* In the 1980s, the SR-71 fleet was refitted with a new digital automatic flight control system, to replace the old analog FCS. Ironically, while A-12s had at least occasionally sports USAF markings, by that time, the markings on SR-71s had been reduced to a discreet minimum. They still kept busy in that decade -- early on, monitoring events in Poland, with a particularly prominent mission being post-strike reconnaissance for Operation EL DORADO CANYON, the 1986 strike on Libya.

However, the SR-71 was not regarded as a significant asset by all Air Force brass, and the Blackbird's adversaries thought the money used to fly SR-71s could be spent elsewhere. Ironically, although the USAF took over the strategic air reconnaissance effort from the CIA, there were Air Force brass who didn't feel the service should be performing that mission. Tactical reconnaissance could be performed by the U-2 -- which had a real-time datalink, while the SR-71 did not. The SR-71 was also expensive to maintain and fly; in addition, it was really only significantly more useful than the U-2 for overflying protected airspace, with improvements in adversary air defenses making it ever more vulnerable.

In any case, the 1st SRS was shut down in 1990, with some of the aircraft sent to museums, others being parked at the "boneyard" at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona, being kept in recoverable storage. One of the SR-71s ended up with the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, this aircraft being flown on 6 March 1990 by pilot Lieutenant Colonel Raymond Yeilding and RSO Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Vida from Los Angeles to Washington DC in 64 minutes, average speed 3,541.7 KPH (2,144.8 MPH).

NASA continued to fly an SR-71A and an SR-71B after the 1st SRS was shut down. The agency also obtained a third SR-71A, but only used it for ground tests. Blackbird advocates in Congress went so far as to mandate in 1995 that the Air Force put the SR-71 back into service, and by 1 January 1997 they were declared operational once more. It was a minimal operation, with one SR-71A pulled out of mothballs, the SR-71A used by NASA for ground tests, and the SR-71B flown by NASA also used to train USAF pilots. They all flew out of Edwards AFB, leveraging off the NASA presence there. They were updated with a datalink system.

The exercise didn't amount to much, and on 27 April 1998, the Air Force announced that it was to be terminated. The very last flight of an SR-71, for NASA, was in 1999. Of the 32 SR-71s built, a dozen were lost, with one aircrew killed; all but one of the accidents were in 1967 to 1972. Many of the SR-71s are now on public display in museums, where the big and unique aircraft makes for an impressive exhibit. The SR-71(BT) is at the USAF Armaments Museum at Eglin AFB in Florida.

* Rumors have long persisted that the reason the SR-71 was retired was to make way for a secret successor. Actually, investigations for a successor had been conducted since before the aircraft went into operation. A study codenamed ISINGLASS was performed by General Dynamics in 1964 for an aircraft capable of Mach 4 or Mach 5, but the design was still judged too vulnerable to Soviet air defenses. In 1965, McDonnell Aircraft performed a study codenamed RHEINBERRY that envisioned a rocket spaceplane launched by a B-52 that skimmed the top of the atmosphere. It would have been capable of Mach 20, but the shock wave produced would have badly degraded reconnaissance imagery. There was no sense in trying to stay in the atmosphere at such speeds; a true spacecraft made much more sense.

No doubt some aerial reconnaissance assets have been developed that remain secret, but if so, nobody has any real clues as to what they are. Secret aircraft generally don't remain secret indefinitely, and the rumors for Aurora went on for so long, without any data emerging on the machine, that the story faded away. In 2013, Lockheed Martin -- the current incarnation of Lockheed -- announced investigation of a Mach-6 "SR-72" reconnaissance platform, but the announcement made it clear that full development of the machine wouldn't happen in the near future. It never did. Space-based surveillance would be the future.

BACK_TO_TOP* As a footnote to the Blackbird story, from the early 1960s Lockheed's Skunk Works proposed a drone derivative of the A-12. Kelly Johnson thought the A-12 would be too big and complicated to make a useful drone itself, but felt that the design and technology could be leveraged into a smaller ramjet drone that could perform the same mission. The drone could be launched by the A-12, it being one of the few aircraft fast enough to allow the drone's ramjet engine to light up properly. The ideas congealed into a formal study for a high-speed, high-altitude drone begun in October 1962. The US National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) backed the idea, with funding scraped up for initial development. The drone itself was given the preliminary designation of "Q-12", and was a very deep secret.

Kelly Johnson wanted to power the Q-12 with a ramjet built by Marquardt for the Boeing BOMARC long-range SAM. Marquardt's plant was close to Lockheed's, helping ensure security, and the two companies had collaborated on several programs in the past. Conversations with Marquardt engineers indicated the BOMARC ramjet could be used -- though the engine, ultimately designated the "RJ43-MA-11", needed some work, since it wasn't designed to burn for much longer than it took a BOMARC to hit a target a few hundred kilometers away. The Q-12's engine had to operate for at least an hour and a half, much longer than any ramjet built to that time.

In order to reduce weight and cost, the Q-12 was not designed to be recoverable. Instead, it would eject its nose section, containing the camera payload and the expensive guidance system. The nose section would descend by parachute for recovery.

A mockup of the Q-12 was ready by 7 December 1962. Radar tests indicated that it had an extremely low RCS, while wind tunnel tests also indicated the design was on the right track. The CIA was not enthusiastic about the Q-12 at first, mostly because the agency was overextended at the time with U-2 missions, getting the A-12 up to speed, and covert operations in Southeast Asia. In contrast, the Air Force was interested in the Q-12 as both a reconnaissance platform and a cruise missile, and the CIA finally decided to work with the USAF to develop the new drone. Lockheed was awarded a contract in March 1963 for full-scale development of the Q-12.

The major initial problem confronted by the design engineers was launch of the Q-12 from the A-12 mother ship. The Q-12 was to be carried on the back of the A-12, with an uncomfortably small amount of clearance between the A-12's fins. The potential for disaster during separation of the drone from the mother ship was obvious.

* The design was finalized in October 1963, and the designations were changed. The drone was now known as the "D-21", while the A-12 launch aircraft was known as the "M-21" -- "M" stood for "Mother" and "D" stood for "Daughter". The project now had the codename "Tagboard".

The production drone, the "D-21A", looked like a stovepipe with a cone in its inlet, with a tailfin, and wings running the length of the stovepipe that gave the drone something of the look of a sweptback manta ray. It was mostly made of titanium, with some elements made from radar-absorbing plastic composites.

___________________________________________________________________

LOCKHEED D-21A:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

5.8 meters (19 feet)

length:

13 meters (42 feet 10 inches)

launch weight:

5,000 kilograms (11,000 pounds)

maximum speed:

4,300 KPH (2,700 MPH / 2,300 KT)

service ceiling:

29,000 meters (95,000 feet)

range:

> 5,550 KM (> 3,450 MI / 3,000 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The reconnaissance payload and guidance systems were carried in a Q-bay about 1.9 meters (six feet) long. These systems were built into a module that plugged neatly into the bay, and was known as a "hatch". As per the original design concept, the hatch would be ejected at the end of the mission, and the drone would then blow itself up with a self-destruct charge. The hatch would be snagged out of the air by a C-130 Hercules -- a technique that had been refined by the Air Force to recover film canisters from reconnaissance satellites.

The M-21 was a two-seat version of the A-12, with a pylon on the fuselage centerline between the tailfins to carry the drone in a nose-up attitude. A periscope allowed the back-seater, or "Launch Control Officer (LCO)", to keep an eye on the D-21. Two M-21s were built new -- they were not modifications of existing A-12s -- along with an initial batch of seven D-21s for test flights.

The first flight of the M-21 and D-21 combination was on 22 December 1964. The D-21 remained attached to the M-21 throughout the flight, since it was simply to study aerodynamics and other systems issues. Refining the scheme until it was ready for an actual release proved troublesome, and the first launch was not until 5 March 1966. The release was successful, though the drone hovered above the back of the M-21 for a few seconds, which seemed to one of the flight crew like "two hours". Kelly Johnson called it "the most dangerous maneuver we have ever been involved in, in any airplane I have ever worked on." The D-21 itself crashed after a flight of a few hundred kilometers.

That was still not too bad for the first flight of such an advanced machine, but the CIA and the Air Force remained unenthusiastic about the program. Kelly Johnson conferred with Air Force officials to see what he could do to tune the project more closely to the service's needs. Among other things, Johnson suggested launching the D-21 from a B-52 bomber and using a solid rocket booster to get the drone up to speed.

A second successful launch took place on 27 April 1966, with the D-21 reaching its operational altitude of 27,400 meters (90,000 feet) and speed of Mach 3.3, though it was lost due to a system failure after a flight of over 2,200 kilometers (1,190 NMI). This was regarded as very satisfactory progress. The successful tests sharpened the interest of the program's government backers, and by the end of the month a contract for 15 more D-21s had been placed.

A third successful flight took place on 16 June 1966, with the D-21 flying through its complete mission, though the hatch wasn't released due to an electronics failure. However, a launch attempt on 30 July ended in disaster. The D-21 collided with the M-21 on release, destroying both aircraft. The two crewmen ejected and landed at sea. The pilot, Bill Park, survived, but the LCO, Ray Torick, drowned when his pressure suit leaked.

* All the fears about launching the D-21 from an A-12 had been proven justified, and Kelly Johnson immediately canceled any more launches from the M-21. However, he felt that the B-52 launch scheme was still practical, and the D-21 program remained alive and well, being re-codenamed SENIOR BOWL.

Adapting the D-21 for launch from a B-52 was not trivial. The drones had to be broken down, modified, and reassembled to allow fitting the attachment points on top to link the drone to the B-52's pylon and the points on the bottom to link the drone to its solid-rocket booster. The modified drone was designated the "D-21B". The booster was hefty, a solid-fuel rocket with a length of 13.5 meters (44 feet 4 inches) and a weight of 6.025 tonnes (13,290 pounds), making it longer and heavier than the drone itself. The booster had a single small tailfin on the bottom to ensure that it flew straight. The tailfin folded to ensure ground clearance. The booster had a burn time of about a minute and a half, and a thrust of 121.4 kN (12,380 kgp / 27,300 lbf).

Two B-52Hs were modified to launch the D-21Bs. They were fitted with very large underwing pylons to carry the drones, replacing the smaller pylons used for the B-52's Hound Dog cruise missiles. Two independent LCO stations were added at the rear of the bomber's flight deck, along with command and telemetry systems; a stellar navigation system to ensure that the drones were launched from well-defined coordinates to reduce flight guidance error; and a temperature control system to keep the drones at a stable temperature before launch.

First attempted launch of a D-21B was on 28 September 1967, but the drone accidentally fell off the B-52's pylon; its booster lit, with the D-21B going straight into the ground. Kelly Johnson called the incident "very embarrassing." Three more launches were performed from November 1967 through January 1968. None were completely successful, so Johnson ordered his team to conduct a thorough review before renewing launch attempts. The next launch was on 30 April 1968, and was also a failure. The Lockheed engineers went back to the drawing board once more, and on 16 June 1968 they were rewarded with a completely successful flight. The D-21B flew a test mission at the specified altitude and course over its full range, with the hatch recovered successfully, though it didn't have a camera payload.

The troubles were not over yet, however. The next two launches were failures, followed by another successful flight in December. A launch near Hawaii in February 1969 to simulate an actual operational flight was a failure as well, but the next two flights, in May and July, were both successes.

The D-21B now appeared ready for operational flights. The first operational mission, part of a program designated "Senior Bowl", was on 9 November 1969, with a D-21B sent to observe Lop Nur. The Chinese never spotted the stealthy drone, but it disappeared and was not recovered. Once again, the Lockheed engineers went back to the drawing board. Another test flight was conducted on 20 February 1970 and was successful.

The next operational mission was not until near the end of the year, 16 December 1970; the D-21B made it all the way to Lop Nur and back to the recovery point, but though the hatch was dropped as planned, it did not deploy its parachute, and was destroyed on impact. The third operational flight, on 4 March 1971, was even more frustrating. Once again, the D-21B made it all the way to Lop Nur and back again, and properly discarded the hatch. The hatch actually deployed its parachute, but the midair recovery failed, and a destroyer that tried to pick the hatch out of the sea simply ran it down. The hatch sank and was lost.

The fourth, and as it turned out last, flight of the D-21B was on 20 March 1971. It was lost over China on the outbound leg, apparently having been shot down. In July, the D-21B program was canceled. Although the program had suffered from more than its fair share of bugs, it appears the main reasons for the cancellation were Nixon's rapprochement with China and operational introduction of the KH-9 / Big Bird reconnaissance satellite.

* When Ben Rich, Kelly Johnson's successor at the Skunk Works, visited Russia in the 1990s after the fall of the USSR, a contact gave him a package that contained parts of the D-21 that had disappeared on the first operational flight. It had crashed in Siberia. The Soviets had apparently been puzzled as to what it was, but it appears that they also obtained the wreckage of the D-21 lost on the fourth operational flight. The Tupolev design bureau reverse-engineered the wreck and came up with plans for a Soviet copy, named the "Voron (Raven)", but it was never built.

38 D-21s were built, with 21 expended. The other 17 were put in mothballs at the Davis-Monthan AFB boneyard near Tucson, Arizona. Since the base is more or less open to the public, the exotic D-21s were eventually spotted and photographed, leading to wild speculations as to their nature that were inflamed by misinformation generated by the Air Force; for example, they were described as test machines used in development of the A-12 / SR-71. The full details didn't come out until 1993, when an author named Jay Miller published a book titled LOCKHEED'S SKUNK WORKS: THE FIRST 50 YEARS that gave a reasonably complete account of the D-21 project. The mothballed drones were passed off to NASA, which took four, and to a number of air museums.

In the late 1990s, NASA considered using their D-21s to test a hybrid "rocket-based combined cycle (RBCC)" engine, which operates as a ramjet or rocket, depending on its flight regime. However, this idea was abandoned, with NASA preferring to use a derivative of the agency's X-43A hypersonic test vehicle for the experiments.

The Seattle Museum of Flight was one of the museums that received a D-21. The museum also had the surviving M-21, and museum volunteers built a pylon to allow mounting a D-21 on its back. The combination is the central exhibit in the main display area, and is one of the most impressive sights in any air museum.

BACK_TO_TOP* Sources include:

* Illustrations details:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 sep 19 v2.0.0 / 01 oct 19 / General clean-up, went to two chapters. v2.0.1 / 01 aug 20 / Cleanup for ebook release. v2.0.2 / 01 apr 22 / Review & polish. v2.0.3 / 01 mar 24 / Review & polish. (+)BACK_TO_TOP