* The Petlyakov Pe-2 was a fast, twin-engined light bomber used extensively by the Soviets in their war against Hitler. This document provides a history and description of the Pe-2.

* Vladimir Mikhailovich Petlyakov learned his trade as an aircraft designer under the instruction of the Russian aviation pioneer N.E. Zhukovskiy. From 1920 onward, Petlyakov worked under Andrei Tupolev, one of the godfathers of Soviet aircraft design. He worked on a number of projects for Tupolev, most significantly heading the design team for the "TB-3 (ANT-6)" bomber of the early 1930s, where "ANT" stood for "Andrei N. Tupolev". The TB-3 was a big four-engine bomber with an open cockpit and fixed landing gear. It looks archaic now, and its service in combat a decade later had few distinctions, but for its time it was an advanced aircraft.

The TB-3 was quickly seen as behind the times, and so there was a push to develop new heavy bombers with more advanced technology. In 1934, two new bomber design programs were initiated to obtain a replacement for the TB-3. The new bomber would feature the latest innovations in aircraft design and would operate at high altitude to avoid interception. It would also have a heavy bombload and strong defensive armament. The engines were to be Mikulin AM-34 water-cooled vee-12 engines, then in development, which were expected to provide 640 kW (840 HP) each initially.

The first design effort was headed by Viktor Bolkhovitinov at the VVS (Voyenno Vozdushniy Sily / Red Air Force) Academy, with the initial flight of the prototype of the "Dalniy Bombarovshchik Akademiya (DB-A) / Long-range Bomber, Academy) on 2 May 1935. The DB-A was an advanced aircraft by the standards of the time, being a large all-metal aircraft with an enclosed cockpit, somewhat along the lines of the contemporary US Boeing XB-15, though the DB-A had fixed landing gear, the main gear in oversized "trousers". A second prototype was built, with 12 production machines following, but through improvements were considered, the program was then abandoned.

That was because the second development effort, from the Tupolev OKB (experimental design bureau) seemed more promising -- this machine being given the official designation of "TB-7", with the internal OKB designation of "ANT-42". The AM-34 engines were problematic, partly because they weren't available at the time, and also because they weren't going to be introduced with optimizations for high-altitude operation. The first problem had to be tolerated, while the second was addressed by installing a Klimov M-100 water-cooled inline vee-12 engine in the center fuselage to drive a blower system that supplied air to the four AM-34s in the wing. It would have been preferable to use an AM-34 in the fuselage instead of the M-100 to simplify maintenance, but it wouldn't fit, and so the smaller M-100 was used instead.

The ANT-42 was to have a bombload of 4,000 kilograms (8,800 pounds) and particularly impressive defensive armament for the time, with power-operated nose, dorsal, and tail turrets, plus gunner's positions at the end of each of the inboard engine nacelles, fitted with a flexible machine gun. Apparently other flexibly-mounted gun positions were considered, but dropped in development. There was a glassed-in gondola under the nose for the bombardier. The pilot and copilot sat in tandem, with positions for flight engineer, radio operator, navigator, and reserve navigator underneath. Total crew complement was to be 11.

The first (unarmed) prototype TB-7 performed its initial flight on 27 December 1936, with Mikhail Gromov at the controls and the aircraft fitted with AM-34FRN engines providing 835 kW (1,120 HP) each. The prototype evaluation was not entirely smooth. The AM-34FRN engines were unreliable -- not surprising since they were pre-production units, and in fact the AM-34 would never go into full production -- and the aircraft was overweight.

The second prototype was built to a near-operational standard, with armament and armor, and performed its first flight on 26 July 1938. Pre-series production of six aircraft had already been authorized, in April 1937, Petlyakov was not present for the first flight, having been arrested and thrown into the Gulag, the prison camp system, in November 1937. The Kremlin had no patience with the delays in the program; in Stalin's USSR, mismanagement was regarded as sabotage, treason, and dealt with accordingly. Direction of the program was taken over by Josef Nezval, who was no doubt highly motivated to get things on track.

However, they didn't. Producing the aircraft proved troublesome, partly because of difficulties in delivering the AM-34 engines and in developing critical components for the air-blower system. In 1939 the Kremlin considered canceling the TB-7, but advocates managed to save the program, partly by obtaining AM-35 inlines and redesigning the pre-series aircraft to accommodate them.

The first TB-7 was delivered in May 1940. By July of that year, Petlyakov had been rehabilitated, and in fact was assigned his own OKB, which retained ownership of the TB-7. The bomber would be soon redesignated "Pe-8" to reflect the change in management. It is not clear when this change was actually made, different sources claiming 1941 or 1942, but the designation "Pe-8" will be used in the rest of this document for simplicity.

* In production, the Pe-8 was fitted with twin ShKAS 7.62-millimeter machine guns in the nose turret, while the dorsal and tail turrets were fitted with a single ShVAK 20-millimeter cannon. The gunners in the rear of the engine nacelles each fired a single flexibly-mounted Berezin 12.7-millimeter machine gun. There had been considerable variation in armament fit during prototype development, and some late-production Pe-8s were delivered with one ShKAS machine gun in the nose instead of two.

The initial production machine were fitted with AM-35A inlines with 1,010 kW (1,350 HP) each. The scheme involving the M-100 engine in the fuselage to drive a blower system was not used in production machines. Following the initial production aircraft, Pe-8s were then built with Charomskiy M-30 and M-40 two-stroke diesels, which proved unreliable, leading to retrofit of AM-35As. Ultimately, problems with delivery of the AM-35A forced conversion to Shvetsov M-82 air-cooled radials, with 1,380 kW (1,850 HP) each. The refit of the air-cooled engines required considerable redesign of the engine nacelles and apparently the elimination of the gunner's positions in the nacelles. Aircrews liked the greater power provided by the M-82s, but found the old AM-35As more reliable.

___________________________________________________________________

PETLYAKOV PE-8 HEAVY BOMBER:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

39.1 meters (128 feet 3.3 inches)

wing area:

188.68 sq_meters (2,031 sq_feet)

length:

23.59 meters (77 feet 4.75 inches)

height:

6.2 meters (20 feet 4 inches)

empty weight:

18,420 kilograms (40,608 pounds)

max loaded weight:

31,420 kilograms (69,268 pounds)

maximum speed:

427 KPH (265 MPH / 230 KT)

service ceiling:

8,400 meters (27,560 feet)

range:

4,700 KM (2,920 MI / 2,540 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The Pe-8 performed the Soviet Union's first bombing raid on Berlin, on the night of 10 August 1941, barely three weeks after the Nazi invasion. It was mostly a propaganda exercise, with only five of the eight bombers on the raid actually reaching Berlin, and then dumping their loads haphazardly. The difficulties with the raid and other Pe-8 operations in the same timeframe were mostly chalked up to the unreliable diesel engines, leading to their wholesale replacement with AM-35As.

Along with conducting long-range night raids, Pe-8s also served as long-range transports, dropping agents and supplies, and delivering diplomats. In April 1942, a Pe-8 performed a non-stop flight to England to deliver embassy personnel and mail, and in May one carried Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and his staff to Britain and the US.

* It is unclear how many Pe-8s were built. Western sources list only 79 built into October 1941, when the state factory building the type had to be abandoned in front of the German invasion, and that the M-82-powered aircraft were mostly or all refits. More credible Russian sources claim that the Pe-8 was actually built into 1944 and that total production was 93 or 96, with later production of new M-82 powered machines from a state factory in Kazan.

In any case, by 1944 the Pe-8 was no longer up to first-line combat against much improved Luftwaffe night fighter defenses, and was retired to second-line duties. It operated in various roles in the postwar period, including operation as a testbed and transport service with Aeroflot, and flew into the early 1950s before being phased out entirely.

The report card on the Pe-8 seems a bit mixed. It was an advanced aircraft for its time, comparing well at least on paper with contemporary British and American heavy bombers, but given the small number built, it made no major contribution to the Soviet war effort, and was clearly not regarded as a weapon deserving of priority production. The Red Air Force was focused on battlefield support, with little emphasis on strategic bombing at the time.

In the postwar nuclear period, strategic bombing would become much more important. The USSR would turn to the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, instead of an indigenous design, as the basis for the Soviet Union's strategic bombing force. B-29s forced down in Siberia would be reverse-engineered and produced as the Tupolev "Tu-4", which would ultimately evolve into the most distinctly Soviet of aircraft, the Tu-95 "Bear".

BACK_TO_TOP* Petlyakov's true success would actually start out as an offshoot of the ANT-42 work. After his arrest in November 1937, he was allowed to go back to his work in aircraft design at a "special technical prison" run by the NKVD, the state security service led by the dreaded Lavrenti Beria. Such technical prisons were nicknamed "sharashkas", a Russian term that roughly translates as a criminal gang, which is how the unfortunate residents were officially regarded.

The engineers in the sharashkas worked long hours, and they were not even allowed the privilege of signing their design documents, instead being issued numbered stamps to identify their work. The only compensation was that the sharashkas were comfortable, at least by the extremely rough standards of the Gulag, and the engineers were likely to survive their imprisonment.

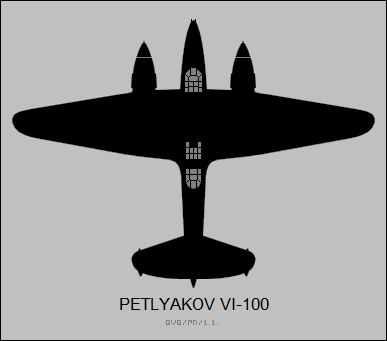

At the sharashka, Petlyakov was assigned to develop a long-range twin-engine fighter to escort the ANT-42, as well as serve as a high-altitude interceptor. Petlyakov and his team of prisoners responded with a design that featured twin engines, all-metal construction, and a pressurized cabin for a crew of two, including pilot and navigator. The new aircraft was designated "Vysotniy Istrebitel 100 (VI-100 / High-Altitude Fighter 100)".

The VI-100 was a very clean aircraft of conventional twin-engine design and a twin-fin tail, with a general configuration along the lines of the German Messerschmitt Bf 110 and some resemblance to Japanese twin-engine aircraft such as the Mitsubishi Ki-46. The VI-100 was powered by twin Klimov M-105R liquid-cooled 12-cylinder vee inline engines -- the M-105R being an enhanced version of the French Hispano-Suiza 12Y engine for which the Soviets had acquired a manufacturing license. The engines were to be fitted with TK-2 turbochargers. Each engine provided 820 kW (1,100 HP) on take-off and drove three-bladed variable-pitch propellers.

The aircraft was designed strong, as per Soviet practice, to handle any class of aerobatic maneuvers, and also included an unusually high number of electrically-actuated subsystems for its time. The pilot and navigator rode in separate cockpits joined by a long, sealed canopy that provided excellent visibility. The crew got into the aircraft using separate ventral hatches, which were equipped with quick-release latches to make bailing out easier. The VI-100 featured taildragger landing gear, all with single wheels, with the main gear retracting backward into the engine nacelles. The tailwheel was also retractable.

The VI-100 was to be armed with two ShKAS 7.62-millimeter machine guns with 900 rounds each and two ShVAK 20-millimeter cannon with 300 rounds each, fitted in a cluster in the nose. There was also provision for a fixed ShKAS machine gun in the tail with 700 rounds of ammunition, to be fired by the navigator in the back seat, but this weapon would never be fitted. The VI-100 could carry bombs on wing racks outboard of the engines. It appears that a secondary bombing role was envisioned for the machine, but there was also some scheme being floated at the time in which the VI-100 would drop clusters of time-delay bomblets into enemy bomber formations.

Initial flight of the first of two prototypes was on 22 December 1939, with pilot Major Pyotr Stefanovsky at the controls. There were some clear bugs, including main landing gear that was a bit too springy and put the machine through some kangaroo-like bounds on landing. This "feature" actually turned out to be lucky, since Stefanovsky found he was undershooting his approach to the runway and was about to smash into some ground equipment, but the aircraft bounded over the top of it. He still had words with the relevant design engineer.

There were more serious problems with the engines, which were gradually fixed, and with the aircraft's landing characteristics. It had a nasty tendency to stall at high angles of attack on approach, which is possibly why Stefanovsky undershot his approach on the first flight. This problem was never completely resolved through the further evolution of the type, and was a danger to inexperienced pilots. The second prototype was wrecked in a landing accident, the aircrew surviving but several unlucky bystanders being killed. Beria was furious, but Petlyakov managed to plead for the well-being of the aircrew. Otherwise, the development program went well, and the VI-100 was recommended for volume production, with plans laid in March 1940 for constructing a pre-production batch of ten machines.

* Stefanovsky took the VI-100 prototype on a public display over Red Square on May Day 1940, with the design crew watching the performance from the roof of their sharashka. However, in that month, Hitler invaded the Low Countries and France, and the work of the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber in that lightning campaign impressed Soviet officials. Soviet efforts to build a diver bomber were going nowhere at the time, and so the word went down in early June 1940 to design a variant of the VI-100 for the dive-bombing role.

Petlyakov's team was given 45 days to come up with the new design. About a hundred more engineers were temporarily recruited from design OKBs on the "outside", and the daily work schedule was stretched, with the engineers given a break and another meal to keep them going. They met their schedule, providing manufacturing drawings and documents to the relevant state factories on 1 August 1940.

The new aircraft was known as the "Pikiruyushchiy Bombardirovshchik 100 (PB-100 / Dive Bomber 100)". It had the same overall configuration as the VI-100 and retained many of its innovations, such as extensive use of electrical systems, but also featured many significant changes. Many of the changes came from analysis of the German Junkers Ju 88A twin-engine bomber. The Soviets and the Nazis were, as it turned out very temporarily, on good terms, and the USSR had purchased a number of Ju 88As from Germany for evaluation.

The cabin pressurization and turbochargers were discarded, with the elimination of the turbochargers leading to streamlining of the engine nacelles. The wings were fitted with perforated dive brakes and the extensions of the tailplane beyond the tailfins were trimmed off. The cockpit was completely redesigned, and a glass-bottomed nose was fitted for the navigator / bombardier.

Two fixed ShKAS 7.62-millimeter machine guns were fitted in the nose. The navigator was provided with a flexibly-mounted ShKAS gun, firing out the back of the cockpit for protection up and to the rear. This gun was stowed under a retractable screen called a "turtle" because of its appearance, with the screen pulled forward when the gun needed to be used.

Along with the bombsight for level bombing in the glass nose, the pilot had a windscreen bombsight for dive bombing. A ventral position for a ShKAS gun on a flexible mount was fitted under the rear fuselage for protection below and to the rear, to be operated by a third crew member who directed the weapon with a periscopic sight, with eyelike portholes on either side of the fuselage to provide more visibility. The gunner doubled as a radio operator. A radio compass was added along with the radio, and a camera was added for reconnaissance and post-strike assessment.

A bomb bay was included in the fuselage, as well as in the rear of each engine nacelle. The main bomb bay could accommodate four 100-kilogram (220-pound) bombs, while the bomb bays in the engine nacelles could carry a single 100-kilogram bomb each. There were external racks between the engines and the fuselage that could carry a total of four 250-kilogram (550-pound) or 500-kilogram (1,100-pound) bombs. Typical bombload was 600 kilograms (1,320 pounds), and maximum bombload was 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds).

* The haste in which the PB-100 program had been conducted meant that the aircraft was to be put into production without construction of a prototype. The state factories assigned to produce the new aircraft were supposed to roll out a working machine by 7 November 1940, but that proved impossible despite threats by the authorities. The command came down that at least one machine had to be produced in 1940, or drastic measures would be taken against those responsible. In the Soviet Union under Stalin, "drastic" tended to be an understatement, and the first PB-100 flew on 15 December 1940. By this time, Petlyakov had been rehabilitated, and the aircraft had been designated "Pe-2", following a new designation scheme put into effect at the beginning of December.

To no surprise considering the circumstances, the first five Pe-2s were in very rough condition, lacking most operational kit and suffering from many defects, and the evaluation that followed in early 1941 uncovered a wide range of problems. Miraculously, none of the aircraft used in the evaluation -- they really were prototypes, whether anybody wanted to admit it or not -- were lost in crashes, but there were a number of emergency landings. However, the evaluation did show that the aircraft was an excellent dive bomber and very rugged, although it had a high landing speed and the unpleasant low-speed stall characteristics noted for the VI-100. The aircraft's high speed, 540 KPH at 5,000 meters (335 MPH at 16,400 feet), more than made up for these vices.

By early spring 1941, the Pe-2 was being delivered to field units. As far as the VI-100 went, its priority dropped as that of the Pe-2 rose, and it was gradually simply forgotten. The ten pre-production machines were never built.

Although the initial Pe-2s had retained the fighter stick control of the VI-100, this turned out to give the pilot inadequate "leverage" and was upgraded to a bomber-type yoke control. The flexible ShKAS light machine gun in the rear of the cockpit was replaced after early production by a more potent Berezin UBT 12.7-millimeter machine gun, and one of the fixed ShKAS guns in the nose was also replaced by a heavy Berezin UBK machine gun -- same as the UBT, but rigged for fixed firing -- with 150 rounds.

Pilots and crew had some difficulties with the Pe-2 at first, since it retained some nasty design defects for the moment, and would always have some unpleasant handling quirks. However, they would grow more fond of it, and refer to it as the "Petlyakov", or the affectionate "Peshka (Pawn)".

BACK_TO_TOP* Several hundred Pe-2s had rolled off the production lines by the time of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. After the Nazi attack, the German Luftwaffe enjoyed almost complete air superiority, shooting down thousands of Soviet aircraft for losses of hundreds of their own.

Most of the Red aircraft were obsolete types and easy kills for the Luftwaffe's Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, but German pilots found the fast Pe-2s difficult to catch and destroy. The British, with a new ally in the war against Hitler, sent a detachment of Hawker Hurricane IIBs to Vianga, near Murmansk, and flew top cover for a Pe-2 bombing mission on 24 September 1941. The Hurricane pilots found they had to stay at full throttle to keep up with the Petlyakovs.

As Hitler's columns rolled into the Soviet Union, as much of the Red industrial machine as could be dismantled was packed up and shipped off to beyond the Urals. Whatever could not be moved was destroyed. Despite the chaos of the relocation, by the end of the year hundreds more Pe-2s had rolled off the production line. Performance deteriorated slightly due to decline in production quality, plus additions of armor for the navigator and radio operator.

Production of reconnaissance Pe-2s began in August 1941, with these aircraft lacking the dive brakes and fitted with additional fuel tankage in the bomb bay plus three cameras in the rear fuselage. They could carry flares for night reconnaissance.

* Soviet resistance through the disastrous summer and fall of 1941 was disorganized and not very effective. Such Pe-2s as were available were not used to their fullest potential, being employed in intermittent bombing sorties and as improvised and ineffectual night fighters, using searchlights mounted under the wings to pin down Luftwaffe bombers for destruction by single-engine fighters.

When the Red Army finally rallied in December 1941, Pe-2s began to make their first significant strikes on the enemy. On 9 December, Pe-2s of the 23rd Bomber Air Division annihilated a retreating German troop convoy, striking at the lead vehicles to block the road and then destroying the rest.

The Soviets endured further setbacks in the spring and summer of 1942. The Pe-2 was able to make the Germans pay for their gains, as Russian pilots perfected tactics, such as the "Vertushka (Carousel)", in which the bombers circled, making successive dive attacks on targets inside the circle. Other tactics were devised to make the best use of fighter escorts, with fighters assigned to provide top cover while two or three followed the dive bombers down to provide flanking protection.

Vladimir Petlyakov was killed in an air crash on 12 January 1942, ironically in a Pe-2. He had been called to a meeting and preferred to ride in his own creation, instead of a VIP transport. The aircraft was believed to have encountered a snowstorm and flown into a hill. Petlyakov was replaced by Alexander I. Putilov.

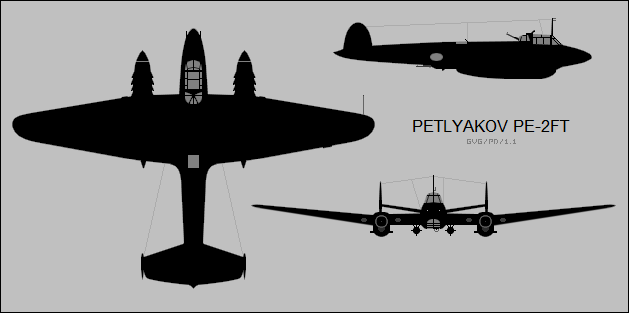

In any case, by late 1942 the design bureau had come up with needed improvements, adding more crew armor and upgrading the ShKAS 7.62-millimeter ventral gun with a Berezin UBT 12.7-millimeter gun. The hand-held dorsal UBT gun position was replaced by a turret, with an distinctive "weather-vane" fixture on top to balance the effects of wind resistance on the barrel when the turret was turned off the centerline. The turret design went through a number of iterations before a proper solution was found. Another noticeable change was simplification and streamlining of the nose, with the elimination of all the bombardier's glazing except for the bottom panels.

The updated Pe-2 was designated "Pe-2FT" for "Frontovoye Trebovaniye (Front-Line Demand)". This designation reflected a sensible process in which front-line pilots had meetings with the design engineers to provide feedback and suggest practical changes. The introduction of the M-105PF engine (with 1,200 kW / 1,610 HP) in February 1943 resulted in improved performance at low altitudes -- but aircrew were unhappy with the change, since the new engine's high-altitude performance was inferior. The main reason behind the use of the M-105PF was to rationalize engine production, since it was also used on Soviet single-engine fighters.

___________________________________________________________________

PETLYAKOV PE-2FT:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

17.16 meters (56 feet 3.5 inches)

wing area:

40.5 sq_meters (435.9 sq_feet)

length:

12.66 meters (41 feet 6.5 inches)

height:

4 meters (13 feet 1.5 inches)

empty weight:

5,870 kilograms (12,943 pounds)

max loaded weight:

8,496 kilograms (18,730 pounds)

maximum speed:

540 KPH (335 MPH / 290 KT)

service ceiling:

8,800 meters (28,900 feet)

range:

1,500 KM (932 MI / 810 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The quirks of the Pe-2's handling led to the development of a two-seat trainer for flight familiarization. This aircraft was sometimes referred to as the "Pe-2UT", and the first was rolled out in late 1942. The Pe-2UT featured duplicate cockpits and controls; it was built in modest quantities through the rest of the war.

* As the Pe-2 was refined, it was thrown into battle after battle: the struggle for Stalingrad through late 1942 into early 1943; the Kursk counteroffensive in the spring of 1943; the Belorussian offensive in 1944; and the final drive on Berlin in 1945. Pe-2 pilots sometimes became proficient "snipers", capable of planting bombs "down chimney stacks". Some of these pilots were women: squadrons led by Captains Nadezhda Fudutenko, Klavdia Fumicheva, and Maria Dolina performed vital service during the battle for Borisov in June 1944.

The type was continuously improved through the conflict, with modifications of armament, external stores, and equipment fit. Near the end of the war, a "Pe-2M" with improved defensive armament was developed but not produced, though a "Pe-2K" with provision for rocket-assisted take-off boosters was built in small numbers. Production of the Pe-2 trailed off after the war.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Pe-2 had its origins in a fighter design, the VI-100, and would evolve back into a fighter of sorts during its lifetime. On 2 August 1941, only days after the German invasion, Petlyakov was ordered to develop a twin-engine long-range fighter version of the Pe-2 on an absolute rush, minimum-change basis. The result, the "Pe-3", performed its first flight on 7 August, only five days after the request was issued!

Of course this was hardly a design miracle, since all the engineers could do on such short notice was take a standard early-production Pe-2 and hastily modify it as a fighter. The changes consisted of fitting additional fuel tanks in the fuselage, one in the bomb bay and one replacing the ventral gunner / radio operator's position, turning the machine into a two-seater.

Nose armament fit was modified by addition of another Berezin UBK 12.7-millimeter machine gun, resulting in nose armament of two UBKs, with 150 rounds per gun, and a single ShKAS 7.62-millimeter gun, with 750 rounds per gun. The rear turret of the Pe-2 was retained, though the ventral gun was removed, to be replaced by a fixed rearward-firing ShKAS light machine gun with 250 rounds in the tail -- a scheme derived from the VI-100 fighter.

One external bomb rack was retained under each wing, along with the bomb bays in the engine nacelles. Typical bombload was about 400 kilograms (880 pounds), though more could be carried in an overload condition. The electrical bomb-release system was stripped, with the mechanical emergency bomb-release system retained. The dive brakes and radio compass were removed; the bomber-type radio was swapped for a fighter-type radio.

It is a further indication of the haste in this program that production was authorized on 14 August 1941, with five pre-production aircraft to be delivered by 25 August. Delivery of these machines was problematic, since it was easier to modify a Pe-2 on short notice than to produce proper engineering drawings and documents for use by the manufacturing engineers to build the aircraft. However, difficulties were overcome, and Pe-3s were being delivered to operational units by the end of the month.

Given the haste behind the effort, the Pe-3 unsurprisingly left something to be desired, with the front-line aircrew immediately calling for changes. The fighter radio had inadequate range, and the lack of a radio compass was very troublesome; forward firepower was inadequate; and the lack of frontal armor left the Pe-3 very vulnerable to defensive fire -- one commander of an air regiment saying that the regiment would be wiped out after two combat actions if armor wasn't fitted.

The Petlyakov OKB responded immediately, with the first improved "Pe-3bis" flying in September -- "bis" being Latin / French for "encore", and roughly equivalent in context to "plus". Nose armament was increased to two UBK 12.7-millimeter machine guns and one ShVAK 20-millimeter cannon, all with 250 rounds per gun. The fixed tailcone ShKAS gun, which was generally regarded as a joke, was deleted. Frontal armor was fitted; automatic slats were added to the leading edges of the wings to improve landing characteristics; provision was added for carriage of a reconnaissance camera; and a number of other small changes were implemented.

These changes were added in ongoing production and, to an extent, retrofitted to aircraft in the field, while the design OKB went through another iteration to further refine the design. In the third pass, the nose glazing was deleted; the two UBK 12.7-millimeter guns in the nose were moved to the wing roots; and a propeller and canopy de-icing system was added.

Pe-3 series aircraft were produced in relatively small batches into 1944, with a total of a few hundred built to end of production, a small quantity compared to the massive quantities of Pe-2s rolled off the production line. They were used for air combat, reconnaissance, and attack, and served to the end of the war. Many Pe-3s were refitted with improved armament in the field.

While the Petlyakov OKB was engaged in the rush job that created the Pe-3, they also worked on another quick modification, the "Pe-2I (Istrebitel / Interceptor)". This was a Pe-2 with fuel tanks and a ShVAK cannon mounted in the bomb bay, as well as provision for underwing external tanks. The Pe-2I did not go into production, but the designation would be recycled later.

BACK_TO_TOP* There were a number of miscellaneous Pe-2 variants and modifications.

There was a series of experiments with different engine fits. A single prototype of a "Pe-2F" was built with turbocharged M-105F water-cooled inline engines and a deeper fuselage that accommodated a more spacious bomb bay to reduce the need to carry "draggy" external stores. Its performance was disappointing, and the turbochargers were troublesome. Experiments followed using M-107 and M-107A engines, but no Pe-2F variant ever went into production.

A prototype, apparently a rebuild of an early production Pe-2, and 22 production Pe-2s were actually built with Shvetsov M-82FN air-cooled radials, the first of these machines flying in June 1942. The aircraft featured big prop spinners to improve streamlining, and the unneeded radiators in the wings were replaced by fuel tanks. The higher power rating of the M-82 provided improved performance, but there were engine reliability problems; although there was work to resolve them, the Lavochin La-5 single-engine fighter had priority for M-82 engine deliveries. There was some notion of redesignating Pe-2 aircraft with M-82FN engines as "Pe-4" machines, but the entire exercise was abandoned.

* In the summer of 1943, Vladimir Myasishchev took over what had been the Petlyakov OKB. He supervised the development of a series of prototypes, including the "Pe-2A", "Pe-2B", and "Pe-2D" that featured a number of aerodynamic improvements over existing Pe-2 production. It appears these were test machines only, with some of the features evaluated on them flowed into standard Pe-2 production. Myasishchev's most interesting development was the "Pe-2I" fast bomber variant, which recycled the designation of an earlier Pe-2 fighter derivative, mentioned previously, though in this case it seems the "I" was just a sequence code and did not stand for "Istrebitel / Interceptor".

Myasishchev's Pe-2I featured extensive streamlining, inspired by the British de Havilland Mosquito light bomber, with no turret but a tail stinger; a deeper fuselage to increase bomb bay volume; M-107A engines; and two crew. A prototype flew in 1944 and performance was excellent, but only five were built before the end of the war and Pe-2 production. Some sources hint that Myasishchev also proposed a high-altitude fighter variant of the Pe-2I, the "Pe-2VI (Vysotnyi Istrebitel)", with a pressurized cabin and four ShVAK 20 millimeter cannon in the nose, but this may be a confusion with a Pe-2VI program conducted by his predecessor, Alexander Putilov, that came to nothing.

* Finally, a number of Pe-2s were used as test platforms during and after the war, including evaluations of downward-firing gun packs for battlefield support; ejection seats; ramjets; and liquid-fuel rockets, one experiment along this line, designated the "Pe-RD", involving Sergei Korolyev, who would become the "Chief Rocket Designer" of the Soviet space program and put the first man into space.

BACK_TO_TOP* Cited production figures for the Pe-2 range from about 10,500 to 11,500. At its height, the Pe-2 comprised 75% of all Soviet twin-engined bombers in operation. The Finns operated several captured examples against the Soviets, and the type was supplied in the postwar period to Czechoslovakia, Communist China, Poland, and Yugoslavia.

One interesting detail concerning the Pe-2 was its use of the AG-2 aerial grenade. A store of them were carried in the tail, to be ejected and explode about 80 meters (260 feet) behind the aircraft to scatter shrapnel in the path of a pursuer. The Soviets claimed that about 1 out of every 5 aerial kills obtained by the Pe-2 were obtained with this weapon.

* Sources include:

Trying to document aircraft is troublesome -- read three different sources, they usually provide three slightly different stories -- but in the case of Soviet aircraft the stories are often wildly inconsistent, and some sources even contradict themselves. I have relied on the Gordon and Khazanov's book as the most definitive source since it is very detailed and seems to be based on primary-source records, though its writing style is jumbled and a real pain to sort through.

History is actually more about records of the past than the past itself. The moving finger having writ and gone on, it is likely that the true facts are often lost forever, and worse, debate over them seems to often muddy matters instead of clarifying them.

* Revision history:

v1.0 / 01 jun 97 v1.1 / 01 sep 98 / Added comments on Pe-8. v1.2 / 25 feb 99 / Review & polish. v1.3.0 / 01 sep 03 / Review & polish. v1.3.1 / 01 sep 05 / Review & polish. v1.3.2 / 01 aug 07 / Review & polish. v1.3.3 / 01 jul 09 / Review & polish. v1.3.4 / 01 jun 11 / Review & polish. v1.3.5 / 01 apr 13 / Review & polish. v1.4.0 / 01 mar 15 / Added DB-A. v1.4.1 / 01 feb 17 / Review & polish. v1.4.2 / 01 jan 18 / Review & polish. v1.4.3 / 01 nov 20 / Review & polish. v1.4.4 / 01 aug 22 / Review & polish. v1.4.5 / 01 jul 24 / Review & polish. (+)BACK_TO_TOP