* The Mustang was one of the weapons that won World War II for the Allies. Although outdated in the postwar period, it still continued to provide good service and evolved in some interesting directions, such as the "F-82 Twin Mustang" and the experimental turboprop "PA-48 Enforcer".

* The long range of the Mustang led to a problem that hadn't been appreciated in earlier fighters: pilot exhaustion on long-range escort missions. Sitting in a relatively tight cockpit for six or seven hours, nursing a powerful aircraft along, and enduring the anxiety and stress of air combat was enough to drain a pilot completely. Sometimes pilots had to be helped out of the cockpit when they returned to base, and the combination of murky English weather and pilot fatigue often led to accidents.

The USAAF was interested in a fighter with even longer range than the P-51D to operate over the wide expanses of the Pacific, particularly as an escort for the long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber. The need to deal with pilot fatigue and provide longer range meant a twin-engine, two-seat aircraft -- but traditionally, twin-engine fighters were no match for single-engine fighters.

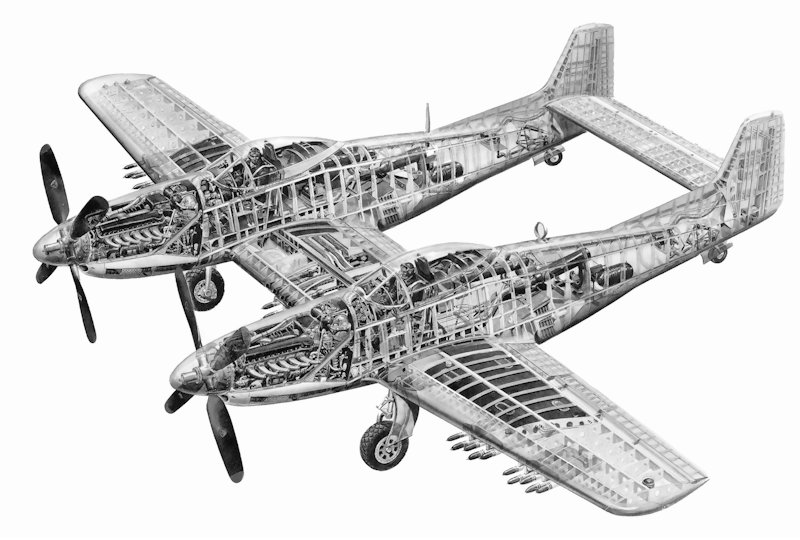

In November 1943, NAA's Edgar Schmued came up with an interesting proposal to address the problem: link two Mustangs together with a common center wing and tailplane. He had actually been tinkering with the idea as far back as 1940. On 7 January 1944, Hap Arnold visited NAA's Inglewood factory and was shown the concept. Arnold was enthusiastic, and gave NAA the go-ahead to proceed with the design, which the company designated "NA-123". In early February 1944, the USAAF ordered four flight prototypes and a static test item of the new design. Two of the flight prototypes were designated "XP-82s" and were to be powered by variants of the Packard V-1650 Merlin, and two were designated "XP-82As", to be powered by variants of the improved Allison V-1710-119 engine with two-stage supercharging.

The first of two XP-82s flew on 16 June 1945, with NAA test pilot Joe Barton at the controls. Barton had actually tried to make the first flight on 25 May, but the machines absolutely refused to get off the runway, and the first actual flight was performed with a half-fuel load. The design engineers were frantic, thinking that the machine was fundamentally flawed, but it turned out that the engines, which contra-rotated, had been installed so that the props swept upward towards the center wing section, which stalled the wing section. The engines were quickly reversed, and on 26 June the XP-82 took off and flew generally as it had been designed to, much to everyone's relief. Only one of the XP-82As was actually completed, being rolled out in the late summer of 1945.

The common center wing section housed all the XP-82's gun armament, consisting of six 12.7-millimeter Browning M2 machine guns with 440 rounds per gun. The center wing section featured a slotted flap running the length of the trailing edge. The wing area of the XP-82 was substantially less than that of two Mustangs, and so the wing had to be strengthened to handle higher wing loading. Longer two-piece ailerons with hydraulic power boosting were fitted to the outer wings to improve roll response.

The XP-82 could be fitted with a total of six stores pylons, two on each outer wing and two on the center wing section, for bombs, HVAR rockets, or drop tanks. Up to 1,800 kilograms (4,000 pounds) of stores could be carried. The center section could also carry a pod for night-fighting radar, machine guns, or reconnaissance cameras. Radar pods would receive further development, as explained below. A gun pod carrying eight 12.7-millimeter Browning guns was developed, but never fielded. A reconnaissance pod was apparently built, but saw little or no use.

The XP-82 was big, 3.1 meters (10 feet 2 inches) longer than a P-51D, and the dorsal fin extension was enlarged to improve yaw stability. There was actually very little parts compatibility between the XP-82 and a single-engine Mustang. The XP-82 had fuel tanks in the outer wings and in each fuselage, giving it a big internal fuel capacity of 2,180 liters (574 US gallons), and correspondingly long range. As mentioned, the twin Packard Merlin engines of the XP-82 rotated in opposite directions, in order to compensate for torque, and so the aircraft was fitted with left-handed and right-handed engines, designed "V-1650-23" and "V-1650-25".

Landing gear had to be revised and strengthened to handle the greater weight. The main gear was hinged in the fuselage, and retracted across the fuselage into the common center wing. The fuselage tailwheel was retained, giving the Twin Mustang an unusual "four point" stance on the ground. The cockpits were largely redesigned from the single-seat Mustang. The command pilot flew in the left cockpit, which was fully equipped. The copilot occupied the right cockpit, with more austere controls to allow him to spell the copilot when need be. A single-seat interceptor version with one cockpit faired over was considered, but nothing came of the idea.

The XP-82A was generally identical to the XP-82, except for Allison engine fit. As with the XP-82, the engines had to be provided in "left handed" and "right handed" versions, and were produced as the "V-1710-143" and "V-1710-144".

* The initial XP-82 prototypes demonstrated impressive performance in early tests. The new aircraft had a top speed of 776 KPH (482 MPH) and a range on internal tanks of 2,237 kilometers (1,390 miles). With four drop tanks installed, the range was 5,550 kilometers (3,445 miles).

The USAAF had enough confidence in North American to order 500 production "P-82B Twin Mustangs" in March 1944, well before the XP-82's first flight. These were Packard Merlin powered aircraft, identical to the XP-82 except for faster-firing M3 machine guns. The contract was cut at the end of the war, and only 20 were actually delivered, in late 1945 and early 1946. These aircraft were used for training and evaluation, except for two of them that were diverted for experiments.

On 28 February 1947, a P-82B named BETTY JO, the ninth production item, piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Thacker (Betty Jo was his wife) and Lieutenant John Ard, set a record for unrefueled flight in a piston fighter, flying from Hickam Field in Hawaii to La Guardia Airport in New York in about 14.5 hours. This aircraft had been stripped down, modified with additional internal fuel tanks, and fitted with four oversized 1,150-liter (310 US gallon) drop tanks. The total distance covered was 7,998 kilometers (4,968 miles) and the average speed was 559 KPH (347 MPH). That was faster than the top speed of most combat aircraft at the beginning of WW II.

* The two aircraft that had been diverted from production were modified as prototype night fighters, with the designations "XP-82C" and "XP-82D". Both aircraft featured a search radar enclosed in a pod on the center wing section. Since the radar had to be set in front of the propellers to ensure that it had a clear field of view, the pod was very long and mounting it was troublesome. The pod was referred to as a "pickle" or a "dong". The XP-82C carried SCR-720C search radar, which had been used on the Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter. The XP-82D carried the less powerful but lighter, and so less difficult to mount, AN/APS-4 radar. Radar operator gear was installed in the right cockpit.

The P-82B and its experimental night-fighter derivatives were the last Merlin Mustangs produced. The last Merlin-powered Twin Mustang would be withdrawn from service in December 1949.

BACK_TO_TOP* While the Merlin-powered Twin Mustangs derived from the XP-82 were only used experimentally or as trainers, the USAAF went ahead to production and operational use of derivatives of the Allison-powered XP-82A.

The USAAF knew that the jet fighter was the way of the future, but early jets didn't have the range for long-range escort missions. In February 1946, the USAF ordered 250 Allison-powered "P-82Es" as interim long-range escort fighters. The order was soon changed to 100 P-82Es, plus 150 night-fighter versions of the Twin Mustang, as detailed below. First flight of the P-82E was on 17 February 1947. In 1947, the US Army Air Forces became the US Air Force, and fighters were redesignated with an "F" for "fighter" instead of the archaic "P" for "pursuit". All P-82s became "F-82s" as a result.

Production F-82Es were slow in arriving, the problem being the updated Allison V-1710 engine. The Allison was selected because Packard had to pay Rolls-Royce a $6,000 USD royalty for every V-1650 the company produced. During the war, Rolls-Royce had been lenient about license fees, but after the end of the conflict, Britain's economy was in the dumps and became more insistent. There was also the fact that General Motors, which owned Allison, had a 40% share in NAA. GM had not been happy with the Mustang's switch to Merlin power during the war, but demand for Allisons by other aircraft such as the P-38 Lightning was strong and GM had not been in a position to protest. With the war over, aircraft production took a dive and GM wanted to sell more Allisons. There were few other reasons to use the Allison engine, since even the two-stage supercharged Allison V-1710 was inferior in power-to-weight ratio to the Merlin.

Unlike the Allisons fitted to early Mustangs, the souped-up Allison engines were also temperamental and unreliable, and Allison couldn't deliver product in quantity. NAA had completed the 100 F-82E airframes by April 1948, but wasn't able to deliver them all for another year due to engine shortages. In service, the Allison-powered F-82Es were marginally slower than the Merlin-powered F-82Bs and the reliability problems persisted. The V-1710 became known as the "Allison time bomb" due to engine failures. Spark plug fouling from backfiring was particularly acute, and spark plugs were often swapped after a single flight.

NAA engineers modified some Allison engines with Merlin components and fixed most of the problems, but Allison took a "not invented here" attitude and insisted on applying their own fixes, which never quite worked. Given the small production run of the Twin Mustang, even the stiff license fee Rolls-Royce was demanding for the Merlin was a bargain compared to all the troubles the USAF had with the Allisons. Pilots still found the machine pleasant to fly, its performance being outstanding even when its engines couldn't be run at their top ratings; in fact, they could lose an engine and hardly notice it. The Twin Mustang was also very agile for an aircraft of its size, and was a very stable gun platform. The battery of guns mounted in the center wing section provided highly focused firepower.

The F-82Es were externally indistinguishable from the F-82As except for minor details. One of the giveaways was the engine exhaust stacks. On the Merlin-powered aircraft, there were six exhaust stacks on each side. On the Allison-powered aircraft, there were duplicate exhaust stacks for each cylinder, for a total of 12 exhaust stacks on each side.

The F-82Es were assigned to Strategic Air Command and flew long-range demonstration missions to show off their capabilities, but they were an interim type indeed. Phaseout began in March 1950, less than a year after the last one was delivered, and was completed by July. Mid-air refueling promised to give jet fighters the range they needed to do the Twin Mustang's long-range escort job.

* The night-fighter versions of the Twin Mustang achieved a bit more distinction in service. In September 1946, the USAAF had ordered 100 "P-82Fs" with AN/APG-28 radar, an improved version of the AN/APS-4 radar used on the P-82D, and 50 "P-82Gs" with SCR-720C radar. These aircraft were Allison powered. Interesting, the big radar pod imposed little performance penalty. The F-82Fs and F-82Gs, as they would be known in service, also featured radar beacons, plus AN/APS-13 tail warning radar.

Before either type was delivered, the USAAF came up with a new requirement for an all-weather fighter for operations in Alaska. Nine F-82Fs were refitted with the SCR-720C radar, essentially turning them into F-82Gs, and both these aircraft and five F-82Gs were fitted with cold-weather gear, including improved heating systems. These were known as "F-82Hs", and were the last Mustangs ever produced by NAA.

___________________________________________________________________

NORTH AMERICAN F-82G TWIN MUSTANG:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

15.62 meters (51 feet 3 inches)

wing area:

37.9 sq_meters (408 sq_feet)

length:

12.92 meters (42 feet 5 inches)

height:

4.21 meters (13 feet 10 inches)

empty weight:

7,256 kilograms (15,997 pounds)

max loaded weight:

11,744 kilograms (25,891 pounds)

maximum speed:

740 KPH (460 MPH / 400 KT)

service ceiling:

11,857 meters (38,900 feet)

combat radius:

1,634 KM (1,015 MI / 885 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The night-fighter Twin Mustangs went into service primarily as interim replacements for the P-61 Black Widow until jet night fighters were available. These Twin Mustangs soldiered on a few more years, until the F-82Hs were finally withdrawn in 1953. They were the last prop-driven air-combat fighters in service with the USAF.

* During their short lifetime, the F-82s achieved one major distinction: holding the fort in Korea until reinforcements arrived. Three squadrons of F-82Gs were operating in Japan as part of the 347th Fighter (All Weather) Group, when North Korea invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950. The F-82Gs were the only aircraft available in Japan that had sufficient endurance to fly to the battle area and operate for hours over the evacuation centers at Kimpo and Inchon. On 27 June, Lieutenant William Hudson and his radar operator, Lieutenant Carl Fraser, scored the first air-to-air kill of the Korean War, shooting down a Lavochkin La-11. Lieutenant Charles Moran shot down a Yakovlev Yak-9 a short time later, and Major James Little increased the day's score to three by destroying a Lavochkin La-7.

The North Korean Air Force had no advanced jet aircraft at the time; the F-82Gs and Lockheed F-80 Shooting Stars quickly cleaned the North Koreans out of the sky. The F-82Gs switched their mission from air combat to night interdiction, using bombs and HVAR rockets to destroy North Korean armor and other targets.

Eventually, the night interdiction mission was taken over by the Douglas B-26 Invader, which was more heavily armed and better suited to the role. The last assignment of the F-82Gs in Korea was to hunt down low-flying Polikarpov PO-2 biplanes that the North Koreans used for night harassment raids, but this was an exercise in frustration since the nimble biplanes were almost impossible to find, much less shoot down. The F-82Gs were finally replaced by Lockheed F-94B Starfires in 1952.

* The American Commemorative Air Force warbird group actually flew a rare F-82E in air shows in the 1980s, painted black to resemble an F-82G night fighter, but the aircraft was lost in an accident in 1985. There are a number of survivors on static display, but no reports of existing airworthy examples.

BACK_TO_TOP* Although the F-82G served an important role in the first few weeks of the Korean conflict, it faded into the background once the US arrived in real force. In contrast, the old P-51D, by then redesignated "F-51D", was a star player through the first year of the war, back in the early Mustang assignment of "mudfighter".

After the end of WW II, piston-engine fighters were rapidly phased out of front-line service in favor of new jet fighters, such as the P-80 Shooting Star. The USAAF retained a few squadrons of P-51Hs, but the older P-51Ds were passed on to the Air National Guard (ANG). As late as 1952, the ANG would still have 68 squadrons flying the Mustang, though the last of them would be gone in 1957.

Most of the remaining Mustangs were either sold to foreign operators or scrapped. In the early summer of 1950, the USAF had three fighter groups operating in Japan that had converted from the F-51D to the F-80, and the old F-51Ds were sitting in storage, waiting to be scrapped. When the war broke out on 25 June, the USAF realized that the F-51Ds were what was needed to help stem the North Korean offensive. The North Koreans, as noted, had no advanced aircraft, and the F-51D had better endurance and warload than the F-80, though some Air Force officers worried with good reason about the Mustang's well-known vulnerability to ground fire. The P-51D could also operate more effectively than jets from primitive airfields. The three fighter groups traded their F-80s back in for their old F-51Ds and were thrown into the battle.

The USAF also grabbed 145 F-51Ds from ANG units and rushed them to Japan on the carrier USS BOXER, which arrived in Tokyo on 23 July 1950. Two squadrons were equipped with the new arrivals, and were quickly flying dozens of sorties a day from rough airstrips behind the front lines in Korea. A squadron each of Mustangs was provided by Australia and South Africa. F-51Ds were also supplied to the South Koreans.

The Mustangs struck at enemy columns with machine guns, bombs, HVARs, and napalm. The bombs and rockets not being particularly accurate, napalm was the preferred weapon for attacking formidable North Korean T-34 tanks, since a napalm bomb saturated a wide area with fire. The attacks were made at low level, however, and Mustang attrition was high. The notorious vulnerability of the Mustang's cooling system was a particular problem. Some thought was in fact given to fielding a squadron of Republic F-47N Thunderbolts, which were better close-support aircraft, but the aircraft were simply not available.

By the fall of 1950, the North Koreans were on the run, and the Americans and their allies were pursuing them into North Korea. Mustangs ranged freely with little air opposition. They claimed five kills during this time, their only air combat victories of the war.

In early November, Mustangs began to encounter fast-jet Mikoyan MiG-15s, and it was only due to the skill of the Mustang pilots and the inexperience of the enemy that the F-51Ds were able to survive. By the time cold weather set in, Chinese forces were pouring into North Korea, driving the Americans and their allies south in a fast retreat that stopped at the South Korean border. The front lines stabilized there, with a static war of attrition following.

With the USAF countering the MiG-15 with the North American F-86, the air combat environment became increasingly too dangerous for piston engine fighters like the F-51D. Most units equipped with the Mustang converted to jets, and by the end of the war in July 1953, only one USAF squadron and some South Korean units were operating the Mustang.

A total of 194 F-51Ds was lost in the war. 172 were destroyed by ground fire, 10 were shot down by enemy aircraft, and 12 were lost to unreported causes. This is said to be the highest loss ratio of any aircraft operated by the Americans and their allies in the Korean War.

* Ironically, the Chinese also operated F-51Ds themselves during the Korean War, though it appears these aircraft never encountered USAF or allied F-51Ds. These Chinese Mustangs had originally been supplied to Chiang Kai-Shek's Nationalists, but had come into the hands of the Communist Chinese after their victory over the Nationalist forces.

They were only one of the many countries to operate the Mustang during WW II or to obtain surplus P-51s in the post-war years. Of course, the Mustang was flown in World War II by the British RAF and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), with Canadian and Polish units operating the type as elements of the RAF.

Britain itself abandoned their Mustangs shortly the end of the war. Under the terms of Lend-Lease, the British were required to pay for them if they kept them, and the RAF had plenty of late-mark Spitfires to meet its needs. In principle they were to have been returned -- but in fact, they were simply scrapped, since the Americans didn't want them back.

Canadian Mustang units had mostly moved on to Spitfires by the end of WW II, but in 1945, the RCAF bought 100 P-51Ds and kept them in service in operational and training roles until the mid-1950s. The Australians, as discussed below, actually built Mustangs of their own, and in fact had more of them than they knew what to do with at one time, though several Australian squadrons put the Mustang to good use in Korea.

The New Zealanders ordered 370 Mustangs before the end of WW II, but with the termination of hostilities only 30 were ever delivered to the RNZAF. These would operate into the 1950s.

South Africa had flown the Mustang during WW II, but the squadron provided by that country as part of the United Nations effort in Korea, mentioned earlier, was supplied with F-51Ds by the USAF and operated under general USAF direction. The SAAF unit was Number 2 Squadron, known as the "Flying Cheetahs".

A few Mustangs were captured during WW II by the Germans and pressed into Luftwaffe service as comparative evaluation aircraft. Ten P-51s also made forced landings in Sweden and were interned. The Swedes found the type very much to their liking; more below.

Before the end of WW II, 40 P-51Ds were provided to the Dutch, and after the war these machines operated in the Dutch East Indies, fighting nationalist insurgents. The insurgents won and formed the state of Indonesia in 1949, which inherited two squadrons of the Mustangs, plus other aircraft, from the departing Dutch. The Indonesians would operate the type in internal conflicts into the 1950s.

The P-51Ds delivered to the Chinese Nationalists were also provided before the end of WW II, with some falling into Communist hands as mentioned, and more were provided to the Nationalists in 1949. They were flown well into the 1950s.

Of the ten P-51s that made forced landings in Sweden during WW II, four of them, two P-51Bs and two P-51Ds, were pressed into Swedish service as the "J-26". Before VE day, the Swedes ordered 50 more P-51Ds, eventually increasing their order to 157 aircraft. The first were delivered in April 1945, with the rest of the deliveries over the following three years. 12 were fitted for reconnaissance under the designation "S-26". All were sold in the early 1950s.

The Swiss acquired 100 F-51Ds in 1948, allowing the Swiss Flugwaffe to finally get rid of its antiquated Bf 109s. The Mustangs were a stop-gap as the Flugwaffe re-equipped with the de Havilland Vampire, which replaced the last Swiss Mustang in 1956.

The French Armee de l'Air operated some P-51s and F-6s for a short time after the end of the war, and the Italians operated 48 F-51Ds from 1948 through 1953.

The Israelis obtained two Mustangs in 1948 and used them in their war of independence. The first combat mission in one of these Mustangs was flown by Gideon Lichtman, a USAAF veteran who had flown the type in the Pacific theatre. In 1952, the Israelis bought 25 more F-51Ds from Sweden, and used them for close-support missions during the 1956 Suez war. Once again, the Mustang proved able to wreak destruction on an enemy with its machine guns, rockets, and napalm, but also as before the aircraft proved vulnerable to ground fire, and a third of them were lost in action. They were phased out of service over the next few years.

In Asia, as mentioned the South Koreans operated the type, as did the Philippines, which used them in counterinsurgency operations. The Mustang proved particularly popular in Latin America, and was operated by a number of Latin American nations. The United States wanted to provide friendly Latin American nations with surplus F-47 fighters, but there were plenty of Mustangs available, and they were cheap. Mustangs were phased out of service in most Latin American countries through the 1970s.

BACK_TO_TOP* The only country besides the US to build the P-51 was Australia, but no Australian-built Mustangs saw combat in World War II. Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) of Australia obtained a license to build the P-51D in 1944, beginning with the assembly of kits provided by NAA. 80 Mustangs were built from kits and given the designation "CA-17 Mustang XX", with the first CA-17 flying in April 1944.

CAC completed 120 Mustangs of their own as well, including:

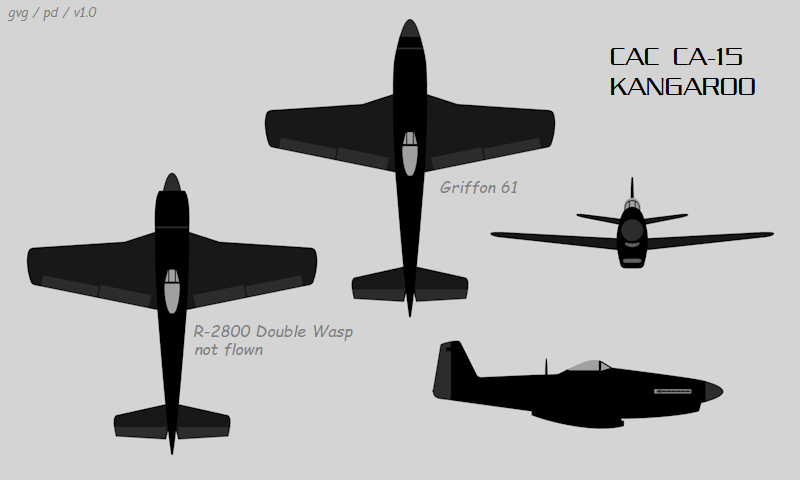

* CAC also built an advanced piston fighter named the "CA-15", powered by the Rolls-Royce Griffon engine, that clearly had Mustang influence though it could hardly be confused as a variant of the type. It looked something like a mutant Mustang on steroids.

The CA-15 began life in 1942 with studies for a follow-on to the Commonwealth Boomerang -- a fighter that the Australians had put together hastily at the beginning of the war, using the North American T-6 Texan trainer as a starting point. The Boomerang was a much better machine than could have possibly been suggested by its humble origins and provided excellent service in the South Pacific theater, but there was no way to make much more of it than it was.

Further studies on a next-generation fighter continued through 1943, though as CAC was working towards Mustang production at the time, the company didn't have many resources to spare and the investigation didn't go anywhere in a hurry. The RAAF finally issued a specification in 1944, calling for a much more capable machine than the Mustang.

Commonwealth originally considered using a turbocharged Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp air-cooled double-row radial engine, but there were doubts that the Australians could get their hands on such engines in adequate numbers. CAC then turned to the Rolls-Royce Griffon water-cooled vee inline engine. In 1945, CAC decided to build a prototype of the "CA-15" with a turbosupercharged Griffon 61 engine with 1,520 kW (2,035 HP) at altitude, and obtained two Griffon 61s from Britain on loan. Production was to use the more powerful Griffon 125, then under development.

A general description of the CA-15 matches that of the P-51D almost perfectly. The CA-15 was a low-wing, all-metal fighter with a vee inline engine driving a four-bladed prop; taildragger landing gear, with the main gear pivoting in the wings toward the fuselage and a retractable tailwheel; a cooling scoop under the fuselage; and a bubble canopy. Armament fit was to be three 12.7-millimeter Browning machine guns in each wing, for a total of six guns, though other gun fits were considered; a single stores pylon under each wing for a 450-kilogram (1,000-pound) bomb or a drop tank, for a total of two stores pylons; or five rails under each wing for rocket projectiles, for a total of ten rails.

However, the CA-15's proportions were entirely distinct from those of the Mustang, and in fact the CA-15 also had a certain resemblance to the Republic XP-72 derivative of the P-47 Thunderbolt. One of the most noticeable oddities was the undersized bubble canopy, like something that would be fitted to an air racer.

Initial flight of the CA-15 was on 4 March 1946, with test pilot Jim Schofield at the controls. Trials showed the machine, which was informally named the "Kangaroo", possessed excellent performance -- though its controls were on the heavy side, and it unsurprisingly demonstrated strong propeller torque on take-off. Trying to get up into the cockpit to fly the thing in the first place was a bit of a chore as well.

___________________________________________________________________

COMMONWEALTH CA-15 "KANGAROO":

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

10.97 meters (36 feet)

wing area:

23.5 sq_meters (253 sq_feet)

length:

11.04 meters (36 feet 2 inches)

height:

4.32 meters (14 feet 2 inches)

empty weight:

3,420 kilograms (7,540 pounds)

max take-off weight:

5,597 kilograms (12,340 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

720 KPH (450 MPH / 390 KT)

service ceiling:

11,900 meters (39,000 feet)

range, internal fuel:

1,850 kilometers (1,150 MI / 1,000 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

A mechanical failure led to a wheels-up landing on 10 December 1946. The pilot, Lee Archer, was unhurt, but the aircraft was badly damaged. By this time, jet fighters were clearly the way of the future, and CAC didn't get the CA-15 flying again until the spring of 1948. On 25 May, Archer dropped the Kangaroo into a dive and then leveled out, to set a speed record of 808.2 KPH (502.2 MPH) for the machine.

Performance would have been even better had the Double Wasp or Griffon 125 been fitted -- but even at that, any leading-edge jet fighter of the time could still leave the Kangaroo in the dust. The CA-15 performed limited further test flights until the spring of 1950, when it was finally grounded due to lack of spares, and then dismantled. The Griffon engines were returned to Britain.

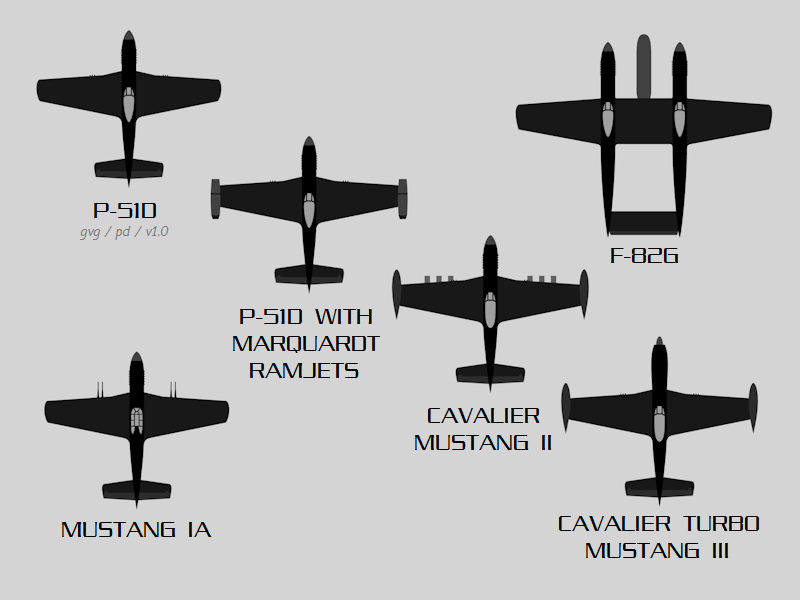

BACK_TO_TOP* Even in the 1960s, there were those who felt the Mustang still had plenty of potential. One of these was David B. Lindsey JR, a newspaper publisher who established a company named Trans-Florida Aviation, which started out by obtaining eight surplus RCAF F-51Ds in 1956 and rebuilding them into a two-seat executive aircraft named the "Cavalier". The Cavalier Mustang attracted enough attention to lead Lindsey to rename his company "Cavalier Aircraft Corporation" in 1962, and acquired the Mustang type certificate and tradename from North American.

The Cavalier Mustang was available in a range of versions, including the "750", "1200", "1500", "2000", and "2500". They were all very similar, the main difference between the variants being an increase in fuel capacity up the numbering sequence, with the Cavalier 2000 and 2500 adding fixed wingtip tanks with a capacity of 416.5 liters (110 US gallons) each. Improvements included a soundproofed and updated cockpit, featuring a flight control arrangement devised by Lindsey and incorporating modern avionics. Of course armament was removed, with the gun ports faired over. Cavalier also fitted out aircraft as per user request, making most of them custom jobs to a degree.

* In 1967, following up interest from the US military, Cavalier developed an updated Mustang for the counter-insurgency (COIN) role. The "Cavalier Mustang II" was a rebuilt F-51D, with a new Packard Merlin V-1650-7 engine; improved avionics; the taller tailfin used on the F-51H; fixed wingtip fuel tanks as per the Cavalier 2000 and 2500; and a reinforced wing to support a total of eight stores pylons, permitting a total stores load of 1.8 tonnes (4,000 pounds). It retained the six Browning machine guns, and also featured a second seat for an observer behind the pilot. Images of Mustang IIs seem to show that they had a canopy with a bulged rear to provide headroom for the back-seater -- but it is unclear if that was standard kit.

That same year, 1967, the USAF ordered a batch of Mustang IIs for delivery to friendly Latin American nations under the US Military Assistance Program (MAP), the program being named PEACE CONDOR; it appears most of the Mustang IIs went to Bolivia, though some may have gone to El Salvador. Cavalier also sold COIN-configured Mustang IIs directly to several other customers. The next year, 1968, the US Army ordered two Mustang IIs as chase aircraft for the YAH-56 Cheyenne helicopter gunship program, and used them in short-lived experiments in close-support applications after the Cheyenne program was canceled.

* In 1968, Cavalier fitted a Mustang with a Rolls-Royce Dart 510 turboprop with 1,245 kW (1,670 EHP) obtained from a Vickers Viscount airliner. Turboprop power was attractive because Merlin engines were getting harder to obtain and maintain, and a turboprop had a longer time between overhauls anyway. The re-engined machine was designated the "Cavalier Turbo Mustang III"; the production machine was to have the standard six 12.7-millimeter Browning machine guns, six stores pylons, self-sealing tanks, and plastic armor.

Cavalier demonstrated the Turbo Mustang III to the USAF, but the service wasn't interested. Cavalier then decided to come up with a more formidable Turbo Mustang, based on the Avco Lycoming T55-L-9 turboprop with 1,830 kW (2,455 SHP), building a single-seat and a two-seat prototype. It was evaluated by the USAF in 1971, but again there was no interest, and later that year one of the prototypes crashed.

That wasn't quite the end of the matter, however, since by that time Piper Aircraft had acquired the effort from Cavalier. Nothing much more happened through the 1970s -- but the US Congress became very interested in a relatively low-cost close-support aircraft, and pressured the Air Force to award a contract for two "PA-48 Enforcer" prototypes in September 1981. The two PA-48s were also powered by the Lycoming T55-L-9 turboprop, but they were not only completely new-build machines, they were almost entirely new designs.

The PA-48s were clearly members of the Mustang family, but they were also clearly bigger and meaner looking. They were 38 centimeters (15 inches) longer, with a bigger tail and a four-bladed paddle propeller; were fitted with plastic armor and self-sealing tanks; and their wings bristled with a total of ten stores pylons. There was also provision for wingtip fuel tanks. They did not have any built-in armament, the plan being that they would carry underwing gun pods instead, and were fitted with an ejection seat.

___________________________________________________________________

PIPER PA-48 ENFORCER:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

12.6 meters (41 feet 4 inches)

length:

10.4 meters (34 feet 2 inches)

height:

4 meters (13 feet 1 inch)

loaded weight:

6,350 kilograms (14,000 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

650 KPH (405 MPH / 350 KT)

service ceiling:

11,465 meters (37,600 feet)

range:

1,480 KM (920 MI / 800 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The first PA-48 Enforcer flew on 9 April 1983, followed by the second on 8 July, but the Air Force had no enthusiasm for the type. They were indifferently evaluated into August 1984, and disposed of in 1986. One of the two prototypes is at the USAF Museum at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, and the other at last notice was at Edwards Air Force Base in California, awaiting restoration.

BACK_TO_TOP* At the end of WW II, the USAAF had far more Mustangs on their hands than they knew what to do with, and sold some of them off at unbelievable prices of a few thousand dollars. The Mustang was hardly a useful aircraft for any ordinary civilian purpose, but they were an extremely impressive toys, and were hot contenders for the air race competitions that were revived in the postwar years.

The National Air Races were resurrected in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1946, and were to continue through 1949. These races featured colorfully-painted surplus warbirds, including the P-51 Mustang, P-38 Lightning, P-39 Airacobra, P-63 Kingcobra, and the F-4U Corsair. These and other "unlimited" air races were terminated when a modified P-51C flew into a house, killing the pilot and a mother and child. Even midget air racing was terminated after an air accident at a race in 1960. Unlimited air racing was revived at Reno in 1964 and continues to this day, with Mustangs as prominent contenders against other piston-engine "brutes" such as Grumman Bearcats and Hawker Sea Furies.

The racers were stripped of armor and other combat gear, and sometimes highly modified as well, with custom features such as tiny canopies. One Mustang was even extensively rebuilt to accommodate a Griffon engine and contra-rotating propellers. The racers had colorful names such as "Miss Foxy Lady", "Specter", "Stiletto", "Galloping Ghost", and the particularly well-known "Red Baron".

While many WW II warplanes are very rare today, since most of them were simply scrapped after the war, the long use of surplus P-51Ds ensured that many survived and eventually found their way into the warbird market. Hundreds are currently flying, and new-build spare parts for P-51Ds are available.

A number of reduced-scale Mustang replicas, powered by air-rated V8 engines and the like, are available to private fliers, generally in kit form, and the general Mustang configuration is often used as a basis for single-seat sport and race aircraft. Such "mini-Mustangs" may not have the status of the real thing, but to those with limited budgets, a small part of a legend is still greatly prized.

* The following list gives Mustang variants and production, starting with the Allison Mustangs:

That gave a subtotal of 1,583 Allison Mustangs. Merlin Mustangs included:

That gave a total of 13,757 Merlin Mustangs and 15,340 Mustangs built by North American.

Commonwealth of Australia also built 40 "CA-18 Mustang 21" machines, same as the P-51D; plus 14 "Mustang 22" machines with a reconnaissance camera, and 66 "Mustang 23" machines, with Merlin engines built by Rolls-Royce instead of Packard. That gave 120 Mustangs built by CAC, and a grand total of 15,460 single-engine Mustangs built. Production of NA-123 Twin Mustangs included:

That gave total production of 273 Twin Mustangs, and total production of all Mustang variants as 15,733.

BACK_TO_TOP* I was not enthusiastic about writing this document at the outset, thinking the P-51 overly familiar. However, investigation of the relatively obscure Allison Mustangs (which were important aircraft in their own right) and the Twin Mustang was good fun -- as was finding out that the P-51, at first glance the most American of aircraft, was hardly a purely American invention. The Mustang owed much to the British, who paid to have it designed in the first place, and ultimately contributed the Merlin engine, bubble canopy, and computing gunsight. The fact that the chief engineer was born and bred German is also an interesting irony.

Writing this document was difficult, not because of the lack of sources but because of the great availability of them. I was easily able to find several books with detailed information on the Mustang, and wading through them all was ultimately exhausting. There came a point where I'd learned about as much as I wanted to.

As usual, there were a number of small inconsistencies between the sources. Most of them were too trivial to want to pursue in a document with no pretensions of being definitive. The purist may want to know if the P-51H ever saw combat service, but the answer "little or none" is correct and seems perfectly adequate.

There were some blatant contradictions between the sources, however. One source stated that the crash of the first prototype was due to Paul Balfour switching on the wrong fuel tank, while another stated in considerably more convincing detail that it was due to the positioning of the carburetor intake. I judged the second version of the story much more plausible, since the photographic record seemed to support it.

* Sources for this document include:

Some of the comments on the Cavalier Mustangs and the Piper Enforcer program were derived from an online article by aviation enthusiast Joe Baugher.

* Illustrations credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0 / 01 jan 99 v1.1 / 01 jan 00 / Review & polish. v1.2.0 / 01 oct 02 / Material on PA-48, CA-15. v1.2.1 / 01 oct 04 / Review & polish. v1.2.2 / 01 aug 05 / Review & polish. v1.2.3 / 01 jul 07 / Review & polish. v1.2.4 / 01 jun 09 / Review & polish. v1.2.5 / 01 may 11 / Review & polish. v1.2.6 / 01 apr 13 / Review & polish. v1.2.7 / 01 mar 15 / Review & polish. v1.2.8 / 01 feb 17 / Review & polish. v1.2.9 / 01 jan 19 / Review & polish. v1.3.0 / 01 dec 20 / Review & polish. v2.0.0 / 01 sep 23 / Illustrations update, some minor reorganization.BACK_TO_TOP