* To ensure that pilots could fly the hot MiG-21, the Mikoyan OKB developed a series of tandem-seat MiG-21 trainers. Both the single-seaters and trainers were also produced by the Chinese as the "J-7" series, which evolved off in new directions from the original Soviet design.

At its peak, the MiG-21 (and J-7) served with dozens of air forces, seeing extensive combat, and still flies with air arms around the world. This chapter describes the MiG-21 trainers and the Chinese J-7 family, and gives a survey of MiG-21 users and combat service.

* At the time of the introduction of the MiG-21F, the standard Soviet advanced jet trainer was the MiG-15UTI "Midget", a tandem-seat variant of the single-seat MiG-15 fighter. The MiG-15UTI was a good trainer and would have a very long service life, but as far as performance went, it wasn't in a league with the MiG-21. That meant that the Mikoyan OKB needed to develop a dual-control two-seater to get novice pilots up to speed on the new, zippy fighter, and the first of two "Ye-6U" prototypes of the supersonic tandem-seat trainer performed its initial flight on 17 October 1960, with Pytor M. Ostapenko at the controls.

The results of trials with the trainer proved satisfactory, with the type entering production as the "MiG-21U" -- where "U" stood for "Uchyebniy (Trainer)" -- with the factory code of "I-66". Machines for Soviet use were built at State Factory Number 31 in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia; export production was built at the Znamya Truda factory near Moscow. Most or all foreign users who obtained MiG-21 fighters or interceptors also obtained some MiG-21Us for conversion training. Soviet pilots called it the "Sparka (Twin)", a general term for a two-seat trainer, while NATO assigned it the reporting name of "Mongol".

Initial MiG-21U production amounted to a minimum-change derivative of the MiG-21F-13. The MiG-21U was exactly the same length as the MiG-21F-13, the tandem-seat cockpit being crammed in by adjusting the arrangement of internal fuel tanks. Since the single NR-30 cannon was deleted, the actual maximum practical fuel capacity was still 2,350 liters (620 US gallons).

The cockpit featured twin canopies that hinged open to the right, with a transparent windbreak between the front and rear positions. The instructor's position in the rear was not raised, giving him a poor forward view. Avionics were much the same as for the MiG-21F-13, including an ASP-5ND gunsight and SRD-5 ranging radar. The MiG-21U could carry an AA-2 Atoll AAM or other store under each wing, and could be fitted with a centerline pod carrying a 12.7-millimeter machine gun for gunnery training.

The MiG-21U deviated from the MiG-21F-13 pattern by moving the pitot tube to the top of the nose and making it a fixed installation, and it also incorporated the fat tires and wing / gear door bulges of the MiG-21P interceptor. It also replaced the double forward airbrakes of the MiG-21F-13 with a single large airbrake. Later production MiG-21Us featured the full-sized tailfin, with the brake chute container at the base.

Although the MiG-21U used the older R-11F-300 engine, since the aircraft rarely carried a full combat load, it was about as much fun to fly as the MiG-21F-13. Performance was so good that in 1965 an early-production machine was refitted with a hotter engine and used to set several women's climb and altitude records, the pilots being Lydia Zaitseva and Natalya Prokhanova. The machine was given the cover designation of "Ye-33".

In 1974, a development aircraft was fitted with an uprated version of the R-11F2S-300 engine, making it a very hot ship indeed, and used to set a series of women's climb records. The pilot was the remarkable Svetlana Savitskaya, who would acquire a list of aeronautic records as long as her arm, and who would become the second woman to fly into space. The first, Valentina Tereshkova, had not been seen as having very good credentials as a cosmonaut, the flight being what might be called in a later day a "correctness exercise", and an unenthusiastic one at that -- but nobody could have disputed Savitskaya's credentials, since they were staggering by any sensible standard.

* The introduction of the blown-flaps system on MiG-21 fighters and interceptors suggested that it might be a good idea to produce a trainer with the blown-flaps system, and so the "MiG-21US" or "I-68" replaced the MiG-21U on the Tbilisi production line in 1966. It was hard to tell from a late-production MiG-21U, the changes being largely internal, the most significant being fit of the uprated R-11F2S-300 engine to support the flap-blowing system.

Other changes included an increase in maximum fuel capacity to 2,450 liters (646 US gallons); the option of fitting four stores pylons instead of two; and replacement of the original SK ejection seats with the better KM-1 seats. The trainee and instructor could each initiate the ejection sequence for both seats, blowing off the canopies and arming the seats, but though the instructor could fire both seats, the trainee could only fire his own.

The MiG-21US was assigned the NATO reporting name of "Mongol-B", the MiG-21U retroactively becoming the "Mongol-A". All production, both domestic and foreign, was from Tbilisi. Later production featured an interesting periscope system for the instructor in the back seat; flight instructors had complained about the bad view from day one, and so a periscope that popped up when the landing gear was deployed was fitted over the rear canopy.

* In 1971, the MiG-21US was replaced on the production line by the "MiG-21UM" or "I-69", which again was built solely at Tbilisi, with the last rolled out in 1975. It was almost identical in appearance to the MiG-21US, the only real external difference being the fit of the AOA sensor and the accompanying offset pitot tube, but the cockpit and avionics were generally updated, with a three-axis autopilot, plus avionics systems on pull-out rack modules to simplify maintenance. The MiG-21UM retained the NATO reporting name of "Mongol-B".

___________________________________________________________________

MIKOYAN MIG-21UM MONGOL-B:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

7.154 meters (23 feet 6 inches)

wing area:

23 sq_meters (247.6 sq_feet)

length (no probe):

13.46 meters (44 feet 2 inches)

height:

4.125 meters (13 feet 6 inches)

empty weight:

5,380 kilograms (11,861 pounds)

normal loaded weight:

8,000 kilograms (17,637 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

2,175 KPH (1,350 MPH / 1,175 KT)

service ceiling:

17,300 meters (56,760 feet)

range:

1,210 kilometers (750 MI / 655 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

A list of MiG-21 variants follows:

Total Soviet production of single-seat MiG-21s was 5,278 at Gorkiy, 3,203 at Znamya Truda, and 17 at Tbilisi -- giving a total of 8,498 single-seaters. In addition, 1,660 two-seaters were built at Tbilisi, giving a grand total of 10,158 Soviet-built MiG-21s. The total doesn't include the 194 MiG-21F-13s built by Aero Vodochody in Czechoslovakia.

BACK_TO_TOP* Red China also produced the MiG-21, though not exactly under license, and the story is complicated enough to be worth discussing in detail. A license agreement was indeed signed in early 1961, with the state factory at Shenyang to perform production -- but Sino-Soviet relations were breaking down at the time, and deliveries of manufacturing specs and materials were broken off before Shenyang had received everything needed to build the aircraft.

The Chinese claimed that the documentation that they did receive seemed to be full of deliberate errors, which the Russians involved later strongly denied. The denial is believable; anybody who's ever worked in a manufacturing environment knows what a nightmare job it is to create and maintain the specs for a complicated product, particularly in the days before specifications were computerized, and had to be provided on stacks of blueprints and volumes of paperwork. Some degree of errors is simply normal -- though in this case the Russians might not have greatly exerted themselves to ensure that everything was in order.

The Chinese ended up, with some difficulty, building the machine anyway without Soviet assistance, designating it the "J-7", where the "J" stood for "jianjiji / jian (fighter)". Aircraft design and production is an elaborate task and Communist China effectively had to develop an entire industry from square one, with the difficulty compounded by China's general lack of industrial infrastructure, and by Mao Zedong's lunatic social initiatives.

The MiG-21 was a fairly sophisticated machine for the Chinese to tackle; it wasn't until 17 January 1966 that they finally flew a prototype of the J-7, with test pilot Ge Wenrong at the controls. The type was passed off for series production to the Chengdu state factory. About a dozen J-7s were built for development, with the initial production version, the "J-7I", performing its first flight in June 1976.

The CAC (Chengdu Aircraft Company) J-7I was very close to a MiG-21F-13, with a WP-7 engine -- a slightly modified version of the R-11F-300 turbojet -- and a single Type 30-1 30 millimeter cannon, a copy of the Soviet NR-30. Its primary AAM was the PL-2, a copy of the AA-2 Atoll. The J-7I was not very satisfactory, a particular complaint being that it featured the original dubious MiG-21 escape system, with the canopy used as a windblast screen; the Chinese implementation proved dangerously unreliable. The J-7I wasn't built in large numbers, though some were exported to Albania and Tanzania under the designation of "F-7A".

For the time being, the Chinese People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) relied on the J-6, a MiG-19 copy and not as big a challenge, while work went on at a slow rate towards a more satisfactory J-7. The first "J-7II" AKA "J-7B" performed its initial flight on 30 December 1978, with Yu Mingwen at the controls. It retained the lines of the MiG-21F-13 but featured a Type II ejection seat, a copy of the Soviet SK ejection seat, and was fitted with a two-piece canopy; a more reliable WP-7B engine, with time between overhauls doubled to 200 hours; and the distinctive brake chute fairing at the base of the tailfin fitted to later Soviet MiG-21 variants.

The J-7II was exported as the "F-7B", and was obtained by Egypt, Iraq, and Sri Lanka. Iraqi F-7Bs were qualified with the French Matra Magic heatseeking AAM, which was also reverse-engineered and built in China as the PL-7 for export sales. Sri Lankan machines were to "F-7BS" standard, with four underwing pylons instead of the traditional two, the outer pylon on each wing being plumbed for a 720-liter (190 US gallon) external tank.

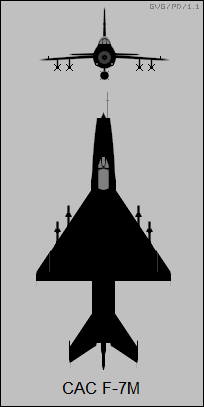

BACK_TO_TOP* Even the more satisfactory J-7II was lagging the times, and so an effort was made to bring the type up to date. One line of work focused on an export variant designated the "J-7IIA" AKA "F-7M", sometimes referred to as the "Airguard", which featured "fast track" improvements with few changes to the basic machine. The J-7IIA was announced in 1984. It looked much like the J-7II but was considerably modernized, with:

The J-7IIA was fitted with twin Type 30-1 30-millimeter cannon with 60 rounds each, and could carry the Chinese PL-2 or the Matra Magic AAMs.

The type was attractive to air forces on a budget and the F-7M was sold to Bangladesh, Egypt, Iran, Myanmar, and Zimbabwe. The Pakistani Air Force (PAF) obtained a variant of the F-7M designated the "F-7P", originally called the "Skybolt", with that name so quickly abandoned that it had to be painted out on early deliveries, which began in 1988. The F-7P was essentially an F-7M with various tweaks as per PAF specification, including a British Martin-Baker Mark 10L zero-zero ejection seat and the ability to carry four US-built Sidewinder AAMs. The PAF went on to obtain an enhanced "F-7PM" that was externally similar but featured US-supplied Rockwell-Collins avionics and Italian FIAR Grifo radar.

There doesn't seem to be any evidence that the PLAAF ever actually obtained the J-7IIA themselves. Sources do mention a "J-7H" in service with the PLAAF, described as a J-7IIA with some optimizations for ground attack, but provide few details.

* In the early 1980s, the Guizhou factory developed a tandem-seat trainer, the "JJ-7", where "JJ" stood for "jianjiji-jiaolianji (fighter trainer)". It was designated the "FT-7" on the export market. The JJ-7 was basically a clone of the MiG-21US, with the periscope and two wing pylons, but featured some Airguard technology. It differed visibly from Soviet "Mongols" by being fitted with twin canted ventral fins, instead of a single ventral fin. Initial flight of the first prototype was on 5 July 1985, with Yan Xiufu at the controls. The PAF obtained their own unique trainer variant, the "FT-7P", without the periscope but four underwing pylons and improved avionics, including the GEC Marconi HUD/WAC.

* In parallel with the development of the Airguard, Chinese industry worked on a more aggressive redesign, essentially trying to build an equivalent to the Soviet MiG-21SM / MiG-21MF. The first "J-7III" or "J-7C" prototype performed its initial flight on 26 April 1984, with Yu Mingwen at the controls. It featured a configuration much like that of the MiG-21SM, with the big intake cone for air intercept radar; a fat dorsal spine; flap blowing; a WP-13 engine equivalent but apparently not identical to the Soviet R-13-300; a CAC zero-zero ejection seat; and a rear-view periscope.

Unfortunately, the J-7III ran into the same problems with weight increase that plagued later Soviet MiG-21 development, and in general did not meet PLAAF spec. Only a few dozen were built. The engineering team tried to save the program with a "J-7IIIA" or "J-7D" that featured an improved radar and WP-13FI engine, but the result was still not satisfactory. After production of another small batch, the program was killed for good.

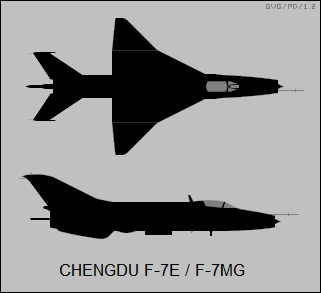

BACK_TO_TOP* The failure of the J-7III program was a disappointment, but not a fatal blow to Chinese aspirations to improve the J-7. Work on another updated J-7 began in 1987 at the Chengdu factory, with a prototype performing its first flight in 1990. In 1992, the Chengdu organization announced the "J-7E", unveiling an "F-7MG" export variant in 1996. The J-7E featured:

The J-7E demonstrated that Chinese aeronautical engineering had reached a certain level of maturity after a climbing up a difficult learning curve -- able to produce innovative and effective designs, instead of just straight copies of foreign machines. Overall, the J-7E looks like it would be tremendous fun to fly, able to run rings around the "classic" MiG-21F-13, with pilots who have flown it saying it is comparable in many respects to an early-production US Lockheed Martin F-16 -- and likely much cheaper.

___________________________________________________________________

CHENGDU (CAC) J-7E:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

8.32 meters (27 feet 4 inches)

wing area:

24.88 sq_meters (267.8 sq_feet)

length (no probe):

13.46 meters (44 feet 2 inches)

height:

4.125 meters (13 feet 6 inches)

empty weight:

5,292 kilograms (11,670 pounds)

normal loaded weight:

7,540 kilograms (16,625 pounds)

MTO weight:

9,100 kilograms (20,065 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

2,175 KPH (1,350 MPH / 1,175 KT)

service ceiling:

19,000 meters (62,340 feet)

combat radius (3 external tanks & 2 AAMs):

850 kilometers (530 MI / 460 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The PLAAF "August 1st" flight demonstration team used a variant of the J-7E known as the "J-7EB", stripped of most combat gear and fitted with a smoke generator, as their mount. The aircraft were painted in a neat red-and-white color scheme.

* The PAF was very interested in the F-7MG; in 2001, the service ordered 60 machines modified to their specifications as the "F-7PG", with Italian FIAR Grifo radar -- replacing the GEC Marconi Super Skyranger radar normally offered for the F-7MG -- and Martin-Baker ejection seats. The J-7E itself has since been improved to the "J-7G" standard, introduced in 2002, with the latest avionics, including an advanced multimode radar suspected to be a license-built variant of the Israeli Elbit EL/M2001, plus a modern ECM suite and a Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite navigation receiver; a single-piece windscreen; and only one cannon. J-7Es have been updated to J-7G standard, being designated "J-7EG" or possibly "J-7L".

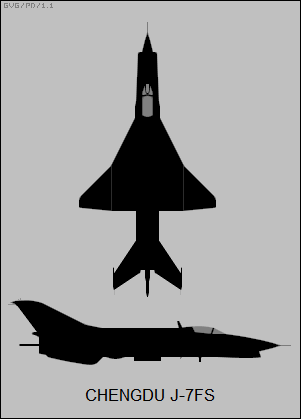

There was some mention of an "F-7MF" derivative of the J-7E, with an intake under the fuselage below the cockpit as with the US F-16, allowing a bigger radar to be carried in the nose, with canard fins to improve maneuverability and wingtip launch rails for AAMs. There is little evidence that the F-7MF was ever flown, but flight pictures of an "F-7FS" prototype, with a nose radome and undernose intake along the lines of that of the US Vought F-8 Crusader, were released. In any case, all J-7 production ended in 2013.

BACK_TO_TOP* Chinese industry worked on a follow-on to the J-7 series, originally referred to as the "Sabre 2" or "Super 7", with models showing an aircraft that looked for all the world like a US Northrop F-20 Tigershark light fighter, with solid nose and side intakes, with MiG-21 wings and landing gear. The Super 7 program was initiated in 1986, being conducted with help from the US Grumman company, but when the US government imposed sanctions on China after the 1989 Tianemen Square massacre, the effort came to a stop.

It was then restarted as the "FC-1 Fierce Dragon" program, with the Pakistanis coming on board under a co-production agreement in 1999. The PAF planned to obtain the aircraft as the "JF-17 Thunder". The first prototype performed its initial flight on 24 August 2003, to be followed by three more prototypes. They were powered by a Russian-made RD-93 bypass jet engine and had seven stores stations, including four underwing pylons, a centerline pylon, and wingtip AAM launch rails.

The long gestation period of the FC-1 led to skepticism that the type would actually go into production. The PLAAF had little interest in the FC-1, the type having been developed to Pakistani requirements. By the spring of 2008, eight JF-17s had been delivered to Pakistan, and the first locally-built JF-17 was rolled out in late 2009, produced by the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC), an arm of the PAF. The JF-17 featured:

50 "Block I" machines were delivered by PAC up to late 2013, with production then moving on to a "Block II" with modernized avionics, heavier weapons load, fixed inflight refueling probe, and improved maintainability. 60 Block II machines were delivered; the Block I machines were updated to Block 2 standard.

A two-seat "JF-17B" AKA "FC-1B" was developed, with a prototype taking to the air in the spring of 2017 and production machines following. It featured:

The aircraft was combat-capable, though it was unclear if the rear cockpit had kit useful for, say, controlling a targeting pod. The Chinese have been working on a WS-13E engine to replace the RD-93, the WS-13E being expected to provide about 10% more thrust. 26 JF-17Bs have been built.

JF-17B tech was leveraged into a "Block III" single-seater update, which added a KLJ-7A active-array radar, plus avionics upgraded all along the line and the RD-93 engine -- with the WS-13 expected later. The radar and other Block III improvements will likely be used to upgrade earlier JF-17 variants. The JF-17 is now being energetically promoted for sales in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, with program officials expecting hundreds of sales -- though so far, the only buyers were Myanmar, which ordered nine, and Nigeria, which ordered three.

The following list summarizes F-7 variants and derivatives:

* The Guizhou organization developed an aircraft comparable to the FC-1 in many ways, in the form of the tandem-seat "Jian Lian 9 (JL-9)" trainer / light attack aircraft. It was derived from the JJ-7, but featured a solid nose, with a FIAR Grifo S7 multimode radar; twin intakes forward of the wing roots; a two-seat cockpit, with the rear seat raised to give a good forward view for the instructor in the back seat; and the cranked arrow wing of the J-7E. The JL-9 was fitted with a WP-13F(C) engine, a glass cockpit with a HUD, countermeasures systems, and a MILSTD 1553B avionics bus. The canopy hinged open to the right. The aircraft had a built-in single-barrel 23-millimeter cannon and five stores hardpoints, with a total load capacity of up to 2,000 kilograms (4,400 pounds).

The initial flight of the first JL-9 prototype was on 13 December 2003, with a redesigned prototype flying in 2007. Early examples were delivered to Chinese forces in 2007, with formal introduction to service in 2011. The early JL-9 for the PLAAF was followed in 2014 by the "JL-9A", with small avionics improvements and new landing lights.

The PLA Navy obtained a "JL-9H" early on -- it seems similar to the JL-9, with no carrier optimizations -- and then a "PL-9G", with a reinforced airframe and arresting hook for carrier landings, a larger wing, and reprofiled forward fuselage. It turned out that it couldn't handle arrested landings, so the tailhook was removed, with pilots training on a ground-based "ski jump" instead of a carrier.

From 2016, the JL-9 was offered on the export market as the "Fighter Trainer 2000 Mountain Eagle (FTG-2000 Shanyang). There has been one sales deal to date, with six obtained by Sudan, all being delivered in 2018. Other African countries are considering purchases as well.

BACK_TO_TOP* By the early 1960s, the MiG-21 was in widespread use in the Soviet Union and in Soviet client states. Of course, the USSR was the biggest user, with more than 6,000 machines -- the 5,200-plus of the single-seaters built at Gorkiy and at least half of the 1,660 two-seaters built at Tbilisi -- serving with the VVS and PVO in all. Variants in Soviet service included the MiG-21F/F-13, the MiG-21P/PF/PFS/PFM, the MiG-21R/S/SM/SMT, the MiG-21bis/bisN, and the MiG-21U/US/UM.

By the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the MiG-21 was in decline as an operational aircraft in its homeland, having been supplanted by the superior MiG-29 and Su-27. Some apparently lingered in use as fighter trainers and in the tactical reconnaissance role, but many MiG-21s were converted to "M-21" target drones, where "M" stood for "mischen (target)".

MiG-21s did continue in service in many Soviet successor states into the 21st century, users apparently including Azerbaijan and Ukraine, but the details are confusing to sort out -- all the more so because there's been a fair market in used MiG-21s, with aircraft changing hands in a perplexing fashion. There has also been a lively if also confusing business in upgrading MiG-21s, with the upgrade programs of various nations mentioned below and the precise details discussed in the next chapter.

The MiG-21 / F-7 was obtained by dozens of states:

The MiG-21 lingers in service with a few air arms, but it's in terminal decline. Although a number of American private fliers have obtained various MiG-15 and MiG-17 variants, there has been no mention of any MiG-21s in private hands -- a pity, since the MiG-21 would be a spectacular airshow demonstrator.

The MiG-21 was generally popular among its users. Although limited in range and warload, its performance was excellent and handling not too intimidating for such a hot machine; it was also very reliable and easy to maintain. It was sometimes flown in natural metal colors, but also sported a wide range of camouflage schemes, for example multi-tone disruptive green patterning on top for northern climates with light blue on the bottom, or multitone disruptive sand-brown patterning on top for desert climates, again with light blue on the bottom. Some color schemes were imaginative, for example the light brown / dark brown "tiger stripe" colors used on Indian Air Force (IAF) machines.

BACK_TO_TOP* It would take time for the "Fishbed" to see action. MiG-21s were stationed in Cuba during the October 1962 Missile Crisis, but that superpower confrontation was defused without coming to serious blows, though it was an frighteningly close thing. The Indian Air Force was operating MiG-21s by the beginning of the September 1965 war with Pakistan, but the Fishbeds were too new to the IAF and did not see real combat. The IAF would make better use of them later.

Various Arab states were supplied with the MiG-21, and on 16 August 1966 Captain Munir Radfa, an Iraqi pilot, defected to Israel in a MiG-21F-13. The defection had been carefully arranged by the Israeli Mossad intelligence service, with two Israeli Dassault Mirage IIIs waiting for his arrival to escort him to landing. The Israelis were very intrigued with the machine and evaluated it thoroughly, giving it the "James Bond" tailcode of "007" -- and when they were done with it, passed it on to their American allies. The Americans gave it the cover designation of "YF-110" and performed the evaluation under a program codenamed HAVE DOUGHNUT. They found the machine had a number of weaknesses -- for example, buffeting prevented it from going supersonic at low altitude; and its engine thrust ramped up slowly, limiting acceleration.

The MiG-21's first real combat was in the June 1967 Mideast War, but unfortunately its major service in the conflict was as a "target". The Arab states were poorly prepared despite their aggressive rhetoric, and a neatly-planned Israeli pre-emptive strike destroyed most Arab air power on the ground. Such machines as survived could only put up scattershot resistance and were generally swept out of the sky immediately by Israeli fighters. An Iraqi MiG-21 did score a hit on an Israeli Dassault Mirage III with an AA-2 Atoll AAM, but failed to knock the aircraft down.

A state of low-level hostilities followed the June War, with occasional air battles. The balance of power in the air still remained tilted towards the Israelis, particularly after they introduced their improved and very lethal Shafir 2 heat-seeking AAM.

* By that time, MiG-21s were seeing plenty of combat over Southeast Asia, with North Vietnamese MiGs contesting fleets of American strike aircraft attempting, with little success, to pound Hanoi into submission. The actual truth of the air combat war over Vietnam is hard to determine, since American sources generally specify a 3:1 kill ratio over North Vietnamese aircraft, while North Vietnamese sources specify just the opposite. The Americans did admit to substantial losses, but believed that SAMs and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) claimed the lion's share of kills.

The discrepancies go down to a lower level of detail as well. American sources say that US pilots found the very agile MiG-17 a more dangerous opponent than the MiG-21, believing that despite the MiG-21's greater speed, the McDonnell-Douglas F-4 Phantom had the edge in power. North Vietnamese sources claim the MiG-21 was more effective.

Despite the disagreements, it does seem clear that the North Vietnamese regarded their interceptor force as a component of a very well-developed and organized air defense network, weighted towards SAMs and AAA. MiGs were operated, following Soviet air-defense procedure, under strict ground control and kept to their own air-defense zones; if they crossed into a SAM or AAA zone, they would be fired upon, no questions asked. The arrangement implicitly assigned the MiGs a subordinate status, and certainly denied North Vietnamese pilots the freedom of movement to take aggressive action.

North Vietnamese fighters were sent into American strike formations to disrupt them and force the attackers to drop their ordnance before reaching their target; kills were a secondary concern. The fact that North Vietnamese fighters forced the Americans to dedicate air combat assets for protective "barrier combat air patrols (BARCAP)" and free-ranging "MiG combat air patrols (MIGCAP)" to protect the formations also imposed an additional load on US planning and resources.

Later in the war, when the US started bombing airfields, the North Vietnamese became very clever at dispersing their fighter assets. Individual aircraft would be slung under Mil Mi-6 heavy-lift helicopters to be taken to sites where they could be hidden easily and protected from air strikes. When needed, they were heli-lifted back to a site with a semi-prepared runway, taking off using RATO boosters. In the end, the Americans lost faith in fighting against a nationalist insurgency in a small Asian country, and had to reluctantly admit defeat. Whatever the truth of the actual kill scores of the North Vietnamese fighter force, it had proven a useful component of the determined and skillful resistance that made the USA throw in the towel.

* In December 1971, India and Pakistan went to war again in a brief conflict that saw the emergence of the new nation of Bangladesh from East Pakistan. The IAF and PAF engaged each other energetically, with IAF MiG-21s proving more than a match for PAF Lockheed F-104 Starfighters, generally regarded as the MiG-21's closest counterpart among US fighters. Not surprisingly, Indian and Pakistani sources differ very greatly on the details of the air war.

In October 1973, the Arabs and Israel had their own rematch, with the Arabs proving much tougher adversaries this time around. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had emphasized intense training and built up, with assistance from the USSR, an impressive air-defense network based on the latest Soviet SAMs and AAA weaponry. The Israeli air force suffered badly in the conflict, though Israeli sources claim most of the kills were inflicted by SAMs and AAA. Arab sources do not agree, claiming that MiG-21s were able to hold their own or better against Israeli Mirages and Phantoms in the air war. However, at the end of the decade the Israelis, having assessed their clear failures in the October War, took on Syrian air power and inflicted a clearly lopsided defeat on them, destroying over a hundred Syrian fighters at minimal losses to themselves. The Israelis also developed tactics to counter and destroy Syrian SAMs and AAA.

* The MiG-21 featured in smaller conflicts later in the 1970s, including a border clash between Libya and Egypt in the summer of 1977, and a war between Somalia and Ethiopia during the same season. The conflict between Somalia and Ethiopia featured fights between MiG-21s from both sides. MiG-21s also flew with the Angolan government in the 1970s and 1980s, occasionally having it out with South African Mirages, with the South Africans claiming a few kills.

The Soviet Union deployed MiG-21s to Afghanistan in 1979, this being the only time VVS MiG-21s saw combat -- and not much at that. The fight with Afghan mujahedin insurgents, which dragged through the 1980s, didn't involve air combat, except for occasional aerial border clashes with PAF fighters; while the MiG-21 couldn't match dedicated close-support types like the Sukhoi Su-25 in the "mud mover" role.

Iraqi MiG-21s and J-7s did see plenty of air combat during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, fighting against Iranian Phantoms and Northrop F-5E Tiger IIs. The F-5E was particularly well-matched against later-model MiG-21s, and Iraqi pilots tended to find the Tiger II a sharp opponent. Iraqi MiG-21s also operated in the 1991 Gulf War, but once again in the role of "targets". The Iraqi use of air power in the war was unbelievably timid, and Coalition forces methodically bombed the Iraqi air force out of existence. In an action that nobody can figure out even today, the survivors fled to Iran, Iraq's long-standing enemy, to be interned. Since that time, however, the MiG-21's combat career went on the fade, and it saw no more real action.

BACK_TO_TOP