* World War II saw the introduction of jet aircraft. One of the most prominent jets of the conflict was the "Messerschmitt Me 262", a twin-jet fighter of advanced design. The Me 262 was recognized after the war as generally superior to anything the Allies had, and helped point the way to postwar aircraft development. This document provides a history and description of the Me 262.

* The Messerschmitt Me 262 was an outgrowth of German turbojet-engine development work that had begun in the mid-1930s, with the initial concepts conceived by an engineer named Hans-Joachim Pabst von Ohain, whose efforts paralleled those of Frank Whittle of Britain.

In 1933, while von Ohain was working on his doctorate at the University of Goettingen, he began to investigate the gas turbine as a basis for an advanced aircraft engine. Although most of the feedback he received suggested that gas turbines would be too heavy for such a role, he pressed on anyway, developing a demonstrator model of a "turbojet" engine in his garage, with the help of a mechanic named Max Hahn.

Von Ohain managed to impress his professor, R.W. Pohl, with a test run of the model. Pohl was both open-minded and well-connected, and in 1936 he sent von Ohain on to aircraft manufacturer Ernst Heinkel with a letter of recommendation. Von Ohain defended his ideas under grilling by Heinkel engineers, and was put in charge of a design team to develop a practical turbojet engine.

* Von Ohain's team had a working bench-test prototype in September 1937, six months after Whittle had reached the same benchmark. Von Ohain's prototype burned hydrogen, an impractical fuel, but further work with Max Hahn led to an engine that burned kerosene.

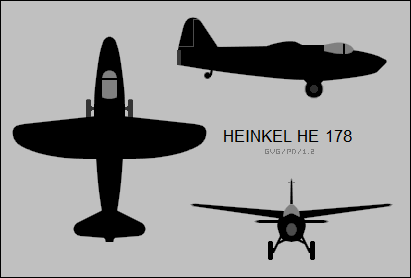

Ernst Heinkel gave the go-ahead to develop a flight-test engine, designated the "HeS 3", which was strapped to an He 118 dive bomber for evaluation. Tests began in May 1939 and continued until the engine burned itself out a few months later. Enough had been learned to build a pure jet-powered experimental aircraft, the "Heinkel He 178", powered by an improved "HeS 3B" engine with 2.94 kN (300 kgp / 835 lbf) thrust. Later in the flight test program, the He 178 would be fitted with a further improved "HeS 6" turbojet with 5.78 kN (590 kgp / 1,300 lbf) thrust.

The He 178 was a simple "flying stovepipe", with straight-through airflow from nose to tail. The aircraft had high-mounted tapered wings and a conventional tail assembly. Although it had fully-retractable tailwheel landing gear, the landing gear was bolted into the down position.

___________________________________________________________________

HEINKEL HE 178:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

7.2 meters (26 feet 4 inches)

wing area:

9.10 sq_meters (97.96 sq_feet)

length:

7.48 meters (24 feet 6 inches)

height:

2.10 meters (6 feet 11 inches)

empty weight:

1,560 kilograms (3,439 pounds)

loaded weight:

1,995 kilograms (4,400 pounds)

max speed:

700 KPH (435 MPH / 378 KT)

___________________________________________________________________

The He 178 performed its first test flight on 27 August 1939, a few days before the outbreak of World War II. The flight lasted about five minutes, with the pilot reporting that the aircraft "had no vibration and no torque like a propeller engine. Everything was smooth, and ... felt wonderful." Von Ohain was now well ahead of Whittle, whose efforts were bogged down, first by official indifference and then by national crisis. Whittle would not fly his own experimental jet aircraft, the "Gloster-Whittle G.40", until May 1941.

The Luftwaffe and the German Air Ministry (ReichsLuftfahrtMinisterium / RLM) were preoccupied with war, and the authorities didn't witness a flight demonstration of the He 178 until November 1939. They were generally unimpressed, since the He 178 was not as fast as the best piston fighters. Heinkel was told: "Your turbojet is not needed. We will win the war on piston engines."

That was not as complacent as it sounded, because the Reich was not expecting a long war -- indeed, those in charge knew Germany would be very hard-pressed to win a long war -- and jets wouldn't be in service by the time the shooting was likely to be over anyway. After a total of about a dozen test flights, the He 178 was sent to the national air museum in Berlin, where it was destroyed in a bombing raid in 1943. A second He 178 was planned but not completed.

* Although the RLM seemed indifferent to the He 178, the ministry was still actively pushing German industry to develop turbojets. In hindsight, it seems that the left and right hands of the RLM were not in agreement, which summarizes much of the Third Reich's attempts to develop advanced weapons.

Hans A. Mauch had become head of rocket development at the RLM in April 1938, and quickly expanded his office's charter to include turbojet development, working with an experimental department under Helmut Schelp in the RLM research branch. By mid-1938, the two men had set up a comprehensive program of jet engine development that was soon sponsoring a range of turbojet and turboprop projects.

In response to RLM urging, the Bramo company began work on a pair of "axial flow" engines. Both Whittle's and von Ohain's engines were "centrifugal flow" engines, which feature a compressor like a pump impeller shoving air into combustion chambers ringing the engine. The compressor in an "axial-flow" engine, in contrast, uses rings of blades to drive air directly back into the combustion chambers.

The two Bramo engines included one with a contra-rotating compressor assembly to reduce torque, which eventually was designated the "109-002", and a simpler engine without the contra-rotating fan scheme that was eventually designated the "109-003". Incidentally, the "109-" suffix was used by the RLM to specify turbine engine projects.

Bramo's works at Spandau were bought out by the BMW concern in mid-1939. BMW engineers had been working on a centrifugal-flow turbojet, but the company quickly decided to abandon their own effort and focus on the two Bramo engines obtained in the buyout. The contra-rotating 109-002 proved too complicated and never flew, the project being abandoned in 1942. The company focused on the simpler 109-003, with fabrication beginning in 1939 and first test runs in 1940. By that time, the engine was known as the "BMW 003".

The Junkers company had actually been working on turbine propulsion since 1936, and was running a bench prototype of an axial-flow turbojet in 1938. In the summer of 1939, the RLM awarded Junkers a contract to develop a simple, powerful axial-flow engine that could be put into production as quickly as possible. A design team under Dr. Anselm Franz conducted the development work on the engine, which became known as the "109-004" and later the "Jumo 004". A full-scale bench-test engine was operating by November 1940.

BACK_TO_TOP* Despite spotty official interest, German companies were working on combat aircraft based on the new turbojet engines. Following the flight tests of the He 178, in the fall of 1939 Heinkel began serious development of an operational fighter, the "He 280", which was to be powered by twin improved Heinkel engines and is discussed below.

Even before this, in the fall of 1938, a Messerschmitt design team under Dr. Waldermar Voight had drawn up concepts for an interceptor fighter with twin turbojet engines. The preliminary designs for "Project 1065", as it was designated, went through an iteration or two and finally resulted in a proposal submitted to the RLM in May 1940.

Messerschmitt's dream fighter had the turbojets mounted in nacelles under the middle of the wings. The wings were slightly swept to ensure proper center of gravity, and had an unusually thin wing for good high-speed performance. Since the wing's features for high-speed performance compromised low-speed handling, a "slat" was added to the front of the outer wings. The slat was automatically extended to improve handling at low speeds. The fuselage had a triangular cross-section and substantial fuel capacity to feed the thirsty engines. The aircraft had fully retractable taildragger landing gear. In July 1940, the RLM ordered three prototypes, under the designation "Messerschmitt 262 (Me 262)", to be powered by BMW 003 engines.

Airframe development far outpaced engine development, and so the first prototype, the "Me 262-V1" ("V" standing for "Versuchs / Experimental"), was fitted with a single Jumo 210G piston engine with 530 kW (710 HP) and a two-bladed propeller for preliminary test flights. First flight was on 18 April 1941. The RLM was becoming more interested in the aircraft, ordering five more prototypes in July 1941, to follow the initial order for three.

The Me 262-V1 was finally fitted with a pair of BMW 003 turbojets, each with 5.40 kN (550 kgp / 1,200 lbf) thrust, in November 1941. The Jumo 210G piston engine was retained, which was fortunate, since the turbojet engines were hopelessly unreliable. On 25 March 1942, Messerschmitt test pilot Fritz Wendel took off, to suffer immediate failures of both turbojets. He managed to make a go-round on the piston engine and land, damaging the aircraft but suffering no injury himself.

Development of the BMW 003 engine was progressing slowly while work on the Junkers Jumo 004 seemed more promising, and so the third prototype, the "Me 262-V3", was fitted with two Jumo 004A pre-production engines with 8.24 kN (840 kgp / 1,850 lbf) thrust each. Wendel took the V3 into the air on 18 July 1942 and found the aircraft extremely impressive. Unfortunately, the V3 prototype was wrecked on its second test flight, three weeks later.

The Me 262V-2 prototype, also powered by Jumo 004As, was not delivered until 2 October 1942. Despite all the delays and problems, the RLM had already ordered 15 pre-production Me 262s in May 1942, and added 30 more to the order that October. The He 280 was inferior in performance and the Me 262 was clearly the better option, but there was still no commitment to put the Me 262 into full production.

The RLM was waffling between production of the Me 262 and the "Me 209", an improved version of the piston-powered Messerschmitt Bf-109 fighter. The head of the RLM, Erhard Milch, was conservative and favored the Me 209 over the much more radical Me 262. However, in the spring of 1943 the tide began to shift towards the jet fighter. The Luftwaffe General of Fighters, Adolf Galland, flew the recently-delivered "V4" prototype on 22 May 1943. He enthusiastically endorsed the type and suggested that the Me 209 be canceled. A few days later, the RLM placed an order for 100 production Me 262s.

Apparently this decision did not clear away all the bureaucratic obstacles. Willi Messerschmitt kept on lobbying to produce both the Me 209 and the Me 262, partly it seems as an exercise in bureaucratic empire-building, and it wasn't until November 1943 that the Me 209 was dropped for good. Even then, the Me 262's political troubles were far from over, and in fact were just about to take a very nasty turn. Hitler, alarmed by the success of Allied amphibious landings in Africa and Italy, was very concerned about developing a fast fighter-bomber ("Jagdbomber / Jabo") to pin down invasion forces on the beaches until reinforcements could arrive to drive them back into the sea.

On 2 November 1943, Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe, and Milch visited the Messerschmitt plant in Augsburg. Goering asked Willi Messerschmitt if the new jet fighter could carry bombs. Messerschmitt answered without hesitation that the Me 262 had been designed from the outset to carry 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds) of bombs, could possibly carry twice as much, and would be easy to adapt to the "Jabo" role.

On 26 November 1943, Hitler inspected the Me 262 at Insterburg, and asked the same question: Can it carry bombs? Messerschmitt gave him the same answer that he had given Goering. Hitler's prayers had been answered. He ordered the Me 262 to be built as a fighter-bomber, and the Me 262 "Jabo" featured prominently in his military plans from then on. There is little record of anyone contesting his decision. The reality was that Messerschmitt completely ignored the will of the Fuehrer and busily worked to put the machine into production as a fighter.

Milch, on reading intelligence reports that the Americans were getting ready to field new bombers such as the Boeing B-29 that would be a handful for existing interceptors, also pressed on with production of the Me 262 as a fighter. Though Milch made agreeable noises about building it as a fighter-bomber, little or nothing was done to that end.

BACK_TO_TOP* Whatever the political issues surrounding the Me 262 program, the real difficulty was that the aircraft was still a long way from being a production machine. At the time, there was only one Me 262 flying, the "V4" prototype. The previous three prototypes had been wrecked one way or another, and the "V5" prototype was being rebuilt to use tricycle landing gear, at the suggestion of Adolf Galland. Given the aircraft's long nose, the taildragger landing gear configuration made forward visibility on the ground extremely poor, and the downward-pointing jets also tore up the runway.

The V5 had fixed nose gear, but was followed by the "V6" in October 1943, which had fully retractable landing gear and was close to production specification, and then the last test prototype, the "V7". By April 1943, 13 pre-production "Me 262A-0s" had been completed, of a total of 23 ultimately built out of the 45 ordered. These aircraft were close to production specification, but some had specialized test fits. For example, the "V12" was modified as a high-speed test article with a smaller canopy and other changes, and was clocked at 1,005 KPH (624 MPH), substantially faster than a standard Me 262.

Some of the pre-production machines were also sent on to the Luftwaffe for operational evaluation by a group organized in April 1944 for the task, designated "Erprobungskommando (Proving Detachment) 262". It seemed like the Me 262 was coming into service at precisely the right of time, since now the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) had adequate numbers of long-range P-51 Mustang fighters to escort bombers on daylight raids over Germany, greatly complicating the air defense of the Reich. The Me 262 might well tilt the balance back to the defenders.

* The problem was that building an adequate force of Me 262s was easier said than done. Messerschmitt was straining to keep up with demands for production of existing aircraft types, a difficulty that had been compounded by a devastating Allied air raid on the company's plant at Regensburg on 17 August 1943. Production had to be relocated to Oberammergau, near the Bavarian Alps. Delivering the temperamental Jumo 004 turbojets was even more troublesome.

Work muddled on into 1944, and then the political disconnect between the left and right hand finally led to an uproar. On 23 May 1944, Goering, Milch, Galland, other senior Luftwaffe officials, as well as Armaments Minister Albert Speer and his people, were called to Hitler's residence at Berchtesgaden to discuss the current fighter production program. The meeting was routine up to the point where production of the Me 262 as a fighter was discussed. Hitler was puzzled: "I thought the 262 was coming as a high-speed bomber. How many of the 262s already manufactured can carry bombs?"

Milch replied: "None, mein Fuehrer. The Me 262 is being manufactured exclusively as a fighter aircraft." After a chilly silence, Milch then pointed out that the aircraft could not be adapted to the "Jabo" role without major design changes, and even then it would not be able to carry more than 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds) of bombs.

Hitler was flabbergasted. Back in November, he had asked if the Me 262 could be adapted to the "Jabo" role, and was given an unqualified YES. He had ordered that it should therefore be built as a fighter-bomber, and nobody had protested the decision. He had been including the "Jabo" Me 262 in his plans for the defense of the Reich against an amphibious landing by the Western Allies, which was expected any time soon and in fact would take place within weeks, on 6 June 1944.

Now Hitler was being told that not only were there no "Jabo" Me 262s, but that the assurances he had been given about its feasibility were false, and to make matters worse, nobody had told him of any of this. That would have angered far milder men than Hitler, and he was furious: "Who pays the slightest attention to the orders I give?! I gave an unqualified order, and left nobody in any doubt that the aircraft was to be equipped as a fighter-bomber!"

Goering made excuses and passed the blame onto Milch, who was soon stripped of most of his powers. Hitler ordered that work now be focused on delivering the "Jabo" version of the Me 262, though he did consent to continued testing of the fighter version as long as it didn't slow down deliveries of the "Jabo" variant. Messerschmitt engineers now belatedly began to fit the "V10" prototype as a fighter-bomber that could carry two 250-kilogram (550-pound) bombs. The result was clearly an improvisation, but since the Arado company was already working on an optimized jet bomber, the "Ar-234", the "Jabo" variant of the Me 262 could serve as an interim solution.

By late June 1944, a fighter-bomber unit, "Erprobungskommando Schenk", had been formed under Major Wolfgang Schenk. A month later, the unit was relocated to France with nine aircraft, in order to oppose the "real" invasion that was expected in the Pas de Calais, an expectation fostered by elaborate and comprehensive Allied deception programs.

The "Jabo" Me 262s in France accomplished little, and with the Allied breakout from Normandy they were gradually pulled back, to end up in Belgium at the end of August. With the invasion now history, Hitler rescinded the order to focus solely on the "Jabo" Me 262 version, and the focus of production returned to the fighter variant. The Fuehrer still insisted that any fighter variants that were built to be easily converted to the "Jabo" configuration on short notice.

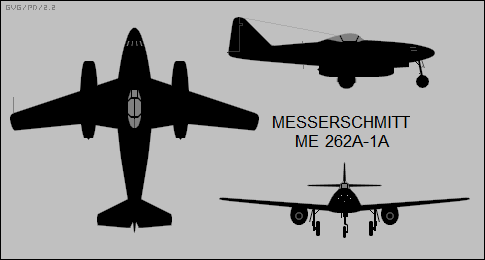

BACK_TO_TOP* The production "Me 262A-1a Schwalbe (Swallow)" fighter that finally emerged was fitted with two Jumo 004B engines with 8.83 kN (900 kgp / 1,980 lbf) thrust each. The "B"-series engines were production standard, using much smaller amounts of "strategic metals" such as chromium, nickel, and molybdenum than the pre-production "A" series engines. That made the "B" series engines substantially lighter than the "A" engines, but at a price, as discussed below.

The Jumo 004's starter system was unusual and worth comment. The compressor of a turbojet has to be brought up to speed before the turbojet can be ignited. In modern aircraft, this is done by a high-torque electric motor or airflow from a small starter turbine engine, while in many earlier jet aircraft it was done using a pyrotechnic cartridge that kicked the turbine into motion. The Jumo 004's starter system consisted of a small two-stroke gasoline engine hidden behind the engine nozzle bullet. The gasoline engine had an electric starter, but as a backup there was a pull-cord starter with the handle in a recess in the front of the bullet. Apparently the BMW 003 had a similar scheme.

The Me 262A-1a was armed with four short-barreled MK 108 30-millimeter cannon in the nose. The MK-108 was a low-velocity weapon, only a step above an automatic grenade launcher, and in fact its explosive shells were referred to as "mines". However, although they didn't have long range, they had terrific killing power. The top pair of cannon had 100 rounds per gun, while the lower pair had 80 rounds per gun. The aircraft was originally fitted with a Revi 16B reflector gunsight, though this was later replaced by the Askania EZ42 gyroscopic gunsight.

The Me 262A-1a had armored front window glass and an armored seat back. The wing had moderate sweepback, with trailing-edge flaps and leading-edge slats. The pilot sat high in an all-round vision canopy that tilted open to the right. The machine was not fitted with an ejection seat. The aircraft was designed to be easy to manufacture, and avoided the use of critical materials.

___________________________________________________________________

ME 262A-1A:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

12.5 meters (40 feet 11 inches)

wing area:

21.70 sq_meters (233.58 sq_feet)

length:

10.58 meters (34 feet 9 inches)

height:

3.83 meters (12 feet 7 inches)

empty weight:

3,795 kilograms (8,380 pounds)

max loaded weight:

6,390 kilograms (14,080 pounds)

maximum speed:

870 KPH (540 MPH / 470 KT)

service ceiling:

12,200 meters (40,000 feet)

range:

1,050 kilometers (650 MI / 565)

___________________________________________________________________

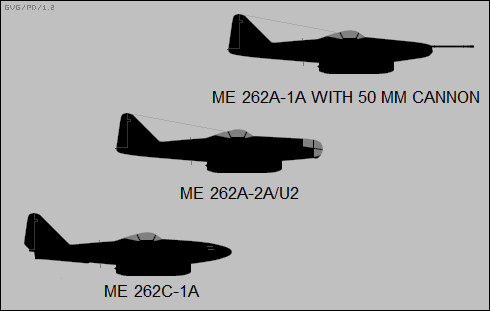

* The "Jabo" Me 262 variant was designated the "Me 262A-2a Sturmvogel (Storm Bird)". As noted, it was fitted with two stores pylons under the forward fuselage for two 250-kilogram (550-pound) general-purpose or cluster bombs, and only had the upper pair of MK 108 30-millimeter cannon.

The Sturmvogel was too "clean" for dive-bombing attacks; it would build up too much speed, becoming uncontrollable. It had no bombsight for performing horizontal bombing attacks from medium or high altitudes, but a skilled pilot could use it to perform useful horizontal attacks at low level, particularly with cluster munitions that didn't have to be aimed precisely.

Cockpit armor was largely eliminated, and an extra fuel tank was fitted in the rear fuselage to increase range. This fuel tank had to be emptied first, otherwise the Sturmvogel became dangerously tail-heavy after dropping its bombs. If that sounds half-baked, it should be noted that a similar fix was made to the North American P-51D Mustang to give it "Berlin & back" range, with similar results. Work was also done on an odd scheme where the Sturmvogel was rigged to tow a large bomb fitted with a small wing, but the aircraft tended to "porpoise" while towing the bomb, with one aircraft losing control and lost, the pilot bailing out safely. Other nasty problems also cropped up and the idea was abandoned, with the final report stating the scheme had proven "hazardous and unsatisfactory".

BACK_TO_TOP* With Allied aircraft operating in ever-increasing numbers over the Reich, operational evaluation of the Me 262 had been difficult, to say the least. Trying to work the bugs out of an aircraft while dodging enemy fighters was far from an ideal situation for flight test.

The evaluation did show that the Me 262 was not only fast but was responsive and docile. However, it did tend to "snake" at high speeds, reducing its accuracy as a gun platform, and it was underpowered, with a long take-off run. Losing an engine was very dangerous, since the Me 262 could barely stay in the air on one engine; if an engine were lost below 290 KPH (180 MPH), the aircraft would usually be lost as well. The engines were also not very reliable, being prone to flameouts and burnouts.

The first documented air combat involving an Me 262 took place on 25 July 1944, when a Schwalbe pounced on an RAF Mosquito that barely managed to escape. One Me 262 was shot down near Brussels on 28 August by a pair of USAAF P-47 Thunderbolts, the first Me 262 to be lost to direct enemy action. An operational fighter squadron, the "Kommando Nowotny", was established out of Erprobungskommando 262 in September 1944, under experienced ace Major Walter Nowotny. Kommando Nowotny became operational on 3 October.

The Me 262 was highly vulnerable on take-off and landing because the Jumo engines took a long time to throttle up; since the engines tended to set asphalt runways on fire, the Me 262 was restricted to operations at airfields with concrete runways, which were more easily targeted by the Allies than dispersed dirt airfields. On 7 October, two were shot down on take-off by Lieutenant Urban L. Drew of the USAAF, flying a P-51 Mustang. The Luftwaffe eventually assigned Fw 190s, when they were available and had fuel, to fly air patrols around the air bases to protect the Me 262s, and the airfields were ringed by heavy flak defenses. The flak installations were a mixed blessing, however, since they were often staffed by poorly-trained and nervous troops who were just as likely to fire on friends as foes.

Many of the Me 262 pilots were also inexperienced, and flying an aircraft with performance greater than any operated before would have been a challenge to more professional aviators. Hitting Allied bombers while streaking through a formation at high speed was difficult, and if an Me 262 pilot slowed down to take more careful aim, he became a good target for the bombers' defensive fire and escorting Allied fighters.

Attrition was high. Nowotny himself was killed in action on 8 November 1944 when his and two other Me 262s were shot down. The few survivors were incorporated into a full Me 262 group, "III/JG7", which achieved a number of kills in the months remaining of the war. Two other groups, "I/JG7" and "II/JG7" were never fully brought up to strength. Four more bomber units were formed but saw little action.

Faced with overwhelming Allied strength and extreme logistical problems, particularly fuel shortages, Me 262 operations during those months were intermittent. An elite unit, "JV-44", was formed up under Adolf Galland, and racked up a number of kills before hostilities ended. Many of these kills were achieved with the new R4M 55-millimeter (2.2-inch) folding fin rockets. An Me 262 could carry a total of 24 such weapons on wooden racks, one under each wing, and if fired into a bomber formation the rockets could have a devastating effect on anything they hit. Schwalbes configured to carry the R4M were given the designation "Me 262A-1b".

A ground-attack version of the R4M rocket was also designed and might have helped turn the Me 262 into an effective "Jabo" aircraft, much like the RAF's rocket-firing Typhoons or "Rockoons", but it does not appear the Luftwaffe ever used the Me 262 in this way.

BACK_TO_TOP* The high performance of the Me 262 made a tandem-seat operational conversion trainer version very desireable, and such an aircraft, the "Me 262B-1a", was introduced in the summer of 1944. The trainer of course had dual controls, with the second seat replacing one of the fuel tanks. Range was extended by fitting two 300-liter (80 US gallon) external tanks under the forward fuselage. About fifteen were built.

The trainer led to the impressive "Me 262B-1a/U1" night fighter, featuring "FuG 218 Neptun" long-wavelength radar and "Naxos" centimetric-radar-homing gear, operated by the back-seater. Armament was two MK 108 30-millimeter cannon and two MG 151 20-millimeter cannon. The type was put through trials in October 1944 by the well-known Hajo Hermann. The Neptun "antler" antennas slowed the aircraft down, but it was still faster than the hated British Mosquito, which preyed on German night-fighters.

During the following winter, Kurt Welter, head of "Kommando Stamp", used Me 262A-1a day fighters for "Wilde Sau (Wild Boar)" night fighting, and in April the unit obtained a few of the Me 262B-1a/U1 night-fighter variants. Despite all the difficulties, Welter claimed 20 kills, making him one of the first jet aces and likely the highest-scoring jet ace in all history.

By the end of the war, Messerschmitt was working on a prototype of the improved "Me 262B-2a" night fighter with a longer fuselage and increased fuel capacity. It was fitted with the Neptun radar at the outset, but there were plans to fit it with the "Berlin" centimetric radar, with improved range and resolutions and a dish hidden in the nose, instead of the clumsy and drag-inducing "antlers" of the long-wavelength radar. There was also consideration of fitting the Me 262B-2a with upward-firing cannon installed in the rear fuselage to allow it to attack RAF bombers from their belly blind spot.

* However, as with all its sisters, the Me 262B-2a was too little and too late. The Jumo 004B engines were never very satisfactory for operational use. The fact that production engines had been designed to minimize use of precious high-strength metals meant that the blades tended to rapidly lengthen or "creep", and the engines sometimes had to be junked after as little as ten hours of flight operations.

Over 1,400 Me 262s were built, but only a relatively small portion of them ever saw action. Fuel was scarce, and Allied aircraft strafed and bombed at will. It appears that the Luftwaffe never had more than 200 on strength at any one time. The Me 262 shot down about 150 Allied aircraft, versus the loss of 100 Me 262s in action, an unimpressive war record.

The Me 262 had no real effect on the course of the war, though it would provide the Allies with plenty of inspiration in the postwar period. It was well in advance of anything the Allies had or had plans to build. Adolf Galland flew British Gloster Meteors in Argentina after the war and felt that if the Meteor's reliable centrifugal-flow engines had been mated to the Me 262's advanced airframe, the result would have been the most formidable of the first-generation jet fighters. The engine, it seems, was another case of the odd tendency to German engineering to be too clever for its own good, in pursuing the more promising axial-flow engine at the expense of the simpler centrifugal-flow engine.

* After the war, Me 262s that had fallen into Allied hands were evaluated by flight test groups, one of the best-known being a USAAF team named "Watson's Whizzers", led by Colonel Harold E. "Hal" Watson of USAAF Air Technical Intelligence. Watson's pilots and ground crew managed to find intact Me 262s at the Lechfeld airstrip in Bavaria, and were assisted in their test flights by German ground crews familiar with the aircraft and even two English-speaking German test pilots, Ludwig Hofmann and Karl Baur. The Me 262s were then shipped to the US on the Royal Navy "jeep" carrier HMS REAPER for further evaluation at Wright Field in Ohio. The tests there included a competitive fly-off against a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star jet fighter that concluded the Me 262 was generally superior.

A small number of Me 262s were completed or rebuilt in Czechoslovakia and flown by the Czech Air Force on an experimental basis. The Me 262A-1a became the "S-92", while the Me 262B-1a trainer became the "CS-92".

BACK_TO_TOP* There were a number of interesting one-off variants of the Me 262:

* Several other variants were considered but not built. The "Me 262 HG" featured wings with greater sweepback for high-speed performance and a "vee" or "butterfly" tail. Another scheme was a fairly sensible plan to build a bomber version with an extended fuselage featuring a real bomb bay. This would eliminate the drag of the external bombs, increasing the speed of the aircraft and allowing it to outpace Allied fighters.

Since the long nose of the Me 262 led to a restricted forward field of view for the pilot, reconnaissance and bomber variants were proposed with the cockpit moved well forward, giving the aircraft something of the look of the Gloster Meteor. There was also a series of "Project 1099" two-seat heavy-fighter proposals which fitted the Me 262 wings and tail to a new, heftier fuselage, as well as a similar "Project 1100" bomber proposal -- but these concepts were discarded, since they were judged likely to be underpowered.

Ramjet and pulsejet boosted versions were envisioned, as well as a "Mistel (Mistletoe)" flying-bomb version of the Me 262 with no cockpit, a warhead in the nose, and a simple autopilot system. The flying bomb was to be controlled by a piloted Me 262 attached to a frame on top, with the whole clumsy assembly taking off on a big trolley that was dropped after take-off. The piloted Me 262 would release the flying bomb after pointing it at a target.

All of these concepts appear to have been nothing more than paper schemes, and it is doubtful that any of them got as far as mockups.

BACK_TO_TOP* Late in the war, the Japanese were shipped a complete Me 262 by submarine. They began work on a copy of the fighter, designated the "Ki-201 Karyu (Fire Dragon)", but it was never completed. They did build and fly a smaller aircraft modeled on the Me 262, the "Nakajima J8N1 Kikka (Orange Blossom)", as an attack aircraft for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). The Kikka looked enough like an Me 262 to be mistaken for it, though its rear fuselage was distinctively different, not tapering towards the tail, and its empty weight was about half that of the Me 262.

The Kikka had folding wings, apparently to permit concealment in caves and the like, since IJN carriers were a vanishing species by that time. It was not fitted with guns, armament consisting of a single 500-kilogram (1,100-pound) or 800-kilogram (1,760-pound) bomb.

The Kikka was powered by a pair of "Ne-20" turbojets with 4.66 kN (475 kgp / 1,050 lbf) thrust each. The Ne-20 was a scaled-down derivative of the BMW 003, designed from photographs provided by the Germans. The Kikka used a pair of solid-fuel "rocket-assisted take off (RATO)" boosters to help get it off the runway.

___________________________________________________________________

NAKAJIMA J8N1 KIKKA:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

10 meters (32 feet 10 inches)

wingspan (folded):

5.26 meters (17 feet 3 inches)

wing area:

13.2 sq_meters (142.1 sq_feet)

length:

9.25 meters (30 feet 4 inches)

empty weight:

2,300 kilograms (5,070 pounds)

loaded weight:

3,550 kilograms (7,825 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

680 KPH (420 MPH / 365 KT)

ceiling:

12,000 meters (39,500 feet)

range:

555 kilometers (345 MI / 300 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Two prototypes of the Kikka were built. The first was rolled out on 25 June 1945, and made its first flight on 7 August 1945, the day before the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. This aircraft flew for a second time on 11 August 1945, but was lost in a flight accident. The second prototype was completed but never flown, and taken to the US by the Americans after the war.

Plans had been made to put the Kikka into production, but the manufacturing plants were destroyed by USAAF bomb raids. Other variants of the Kikka were planned, including a two-seat trainer, an unarmed reconnaissance aircraft, and an interceptor with twin 30-millimeter cannon. Improved "Ne-130" and "Ne-330" powerplants, with about 8.83 kN (900 kgp / 1,985 lbf) thrust, were also in development for the advanced Kikka variants. Under the circumstances, all the developments of the Kikka were little more than fantasies. The fact that the Japanese actually built two prototypes was remarkable in itself, given the devastated condition of Japanese industry at the time.

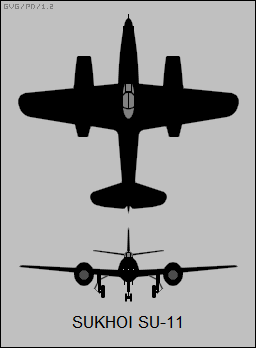

* The Soviets also built "clones" of a sort of the Me 262 after the war. The Sukhoi "Su-9" single-seat fighter had a general configuration like that of the Me 262 and was fitted with Soviet-built copies of the Jumo 004 engine (with the designation "RD-10"), since the Lyulka engines originally intended for the aircraft were not available. It was, however, not really a copy of the Me 262, work having begun in 1944, though the final design was no doubt influenced by examination of Me 262s captured at the end of the war.

The Su-9 performed its first flight on 13 November 1946, with test pilot Georgiy M. Shiyanov at the controls. It was armed with one Nudelman N-37 37-millimeter and twin Nudelman N-23 23-millimeter cannon, and could carry two 250-kilogram (550-pound) bombs or one 500-kilogram (1,100-pound) bomb. It was one of the first Soviet aircraft with an ejection seat -- a copy of the ejection seat used on the German Heinkel He 162 lightweight jet fighter -- and had provisions for RATO boosters and a drag chute.

Only one Su-9 was built; the second prototype ended up as the "Su-11", which was much the same, but featured a number of aerodynamic improvements and used Soviet-designed Lyulka TR-1 turbojets with 12.75 kN (1,300 kgp / 2,870 lbf) thrust each, the TR-1 being essentially the powerplant that had been considered at the outset for the Su-9. Initial flight was on 28 May 1947, again with Shiyanov at the controls.

___________________________________________________________________

SUKHOI SU-11:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

11.80 meters (38 feet 8 inches)

wing area:

21.40 sq_meters (230.35 sq_feet)

length:

10.57 meters (34 feet 7 inches)

height:

3.72 meters (12 feet 2 inches)

empty weight:

4,495 kilograms (9,910 pounds)

loaded weight:

6,350 kilograms (14,000 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

910 KPH (565 MPH / 490 KT)

___________________________________________________________________

However, the Lyulka engines were by no means ready for series production, and the Su-11's high-speed handling left much to be desired. The USSR had more promising jet fighter programs in the pipeline and so the Su-11 program was canceled. Concepts for a two-seat trainer and all-weather interceptor based on the design never got to the hardware stage. Both the "Su-9" and "Su-11" designations would be "recycled" and used on entirely different Sukhoi aircraft, the series of interceptors given the NATO reporting name "Fishpot".

* An American aviation "interest group", the "Me 262 Project", has built replicas of single-seat and twin-seat Me 262s. These aircraft are authentic down to the rivets, one major exception being the use of modern General Electric J85 nonafterburning turbojets rather than the pathetically unreliable Jumo 004Bs. The J85 nonafterburning turbojet was used on the T-2 Buckeye trainer and provides 13.14 kN (1,340 kgp / 2,950 lbf) thrust, substantially more than that of the Jumo 004B. The smaller J85s are fitted in the original Me 262 nacelle design using special mounting hardware so that the aircraft's external appearance remains unchanged.

Initial flight of the first replica, a two-seater, was on 20 December 2002, though it suffered a landing gear collapse on its second flight. The pilot was uninjured, but the aircraft was laid up for six months with repairs. By the fall of 2005, the group had the two-seater back up in the air, joined by a single-seater. The group planned to build a total of five aircraft in all; it is not clear how many were actually completed.

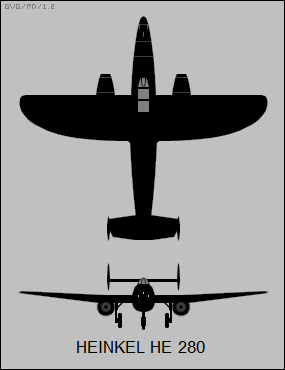

BACK_TO_TOP* The development of the Heinkel He 280 fighter ran in parallel to that of the Me 262, and for a time the He 280 remained an alternative to the Me 262. Preliminary design of the He 280 apparently began in the summer of 1939, while the He 178 was going into flight tests, but in any case work started in earnest on the Heinkel fighter in the fall of the 1939. The design team was under the supervision of Dr. Heinrich Hertl, with chief designer Karl Schwaerzler.

The first "He 280-V1" prototype was completed in the fall of 1940. The He 280 design had a general configuration roughly similar to that of the Me 262, with twin turbojets mounted on the wings, but differed considerably in detail. Its wing had a straight leading edge, with an elliptical trailing edge on the outer half, and it had a twin-fin tail.

The He 280 did not have an all-round vision canopy, but it had tricycle landing gear from the start. It had an ejection seat, making it the first aircraft to be designed from the outset with such a feature. The ejection seat was propelled by a compressed-air charge. The He 280 was to be armed with three MG 151/20 20-millimeter cannon in the nose, though the V1 prototype was not fitted with guns. It was to be powered by two HeS 8A centrifugal-flow turbojets, initially providing 4.90 kN (500 kgp / 1,100 lbf) thrust each.

A total of nine prototypes, from the "He 280-V1" through the "He 280-V9", was built. Sources vary wildly on the differences between these prototypes and the exact chronology of their flight histories, and it is unclear if all nine of these prototypes ever actually flew. It is clear that the initial prototype, the "He 280-V1", began flight tests as a glider in the early fall of 1940, and that the first powered flight of an He 280 prototype was on 2 April 1942. In any case, this was the first flight of a twin-jet aircraft and the first flight of a jet fighter. The flight was performed with the landing gear down and the engines left uncowled, since the cowlings accumulated fuel from leaks that were proving hard to track down.

Although flight tests of the type were promising, the RLM showed little interest. In desperation, Ernst Heinkel arranged for a mock combat between the He 280 and a Focke-Wulf Fw 190. The He 280 of course won the fight, and the RLM was impressed enough to express interest in an initial production batch of "He 280A" machines for evaluation.

___________________________________________________________________

HEINKEL HE 280A-0:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

12.2 meters (40 feet)

wing area:

21.50 sq_meters (231.43 sq_feet)

length:

10.4 meters (34 feet 1 inch)

height:

3.06 meters (10 feet)

empty weight:

3,055 kilograms (6,375 pounds)

loaded weight:

4,300 kilograms (9,480 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

900 KPH (540 MPH / 470 KT)

range:

970 kilometers (603 MI / 524 NMI)

Performance figures are of course estimates, since this particular

configuration was never built.

___________________________________________________________________

In the meantime, problems with the development of the Heinkel-Hirth turbojet led the Heinkel design team to consider the BMW 003 and Jumo 004A turbojets, with some of the prototypes re-engined for evaluation with such powerplants. Some of the prototypes were also fitted with armament,

The initial prototype, the He 280-V1, was also re-engined with four Argus pulsejets -- but that seems to have been strictly an engine test fit, and in any case the aircraft was lost on its first test flight with the pulsejets after being towed to altitude. It is an indication of the confusing history of the He 280 that this is cited as occurring either in early 1942 or early 1943, depending on the source.

Development of the He 280 seemed to be going well, but further evaluation of the Me 262 demonstrated the superiority of the Messerschmitt design, and on 27 March 1943 the RLM ordered all further development of the He 280 as an operational type to be abandoned. Some of the prototypes were later used for aerodynamic testing, including experiments with "vee"-style tails, and for engine flight tests.

BACK_TO_TOP* The story that the Me 262 could have made a major difference in the war if not for Hitler's insistence that it be built as a fighter-bomber seems to exist in a fuzzy state between myth and fact. Most recent documents on the Me 262 suggest that the teething problems with the Jumo 004 engines were really the critical path for aircraft development, and though Hitler's insistence on development of the aircraft as a "Jabo" led to a bureaucratic fiasco, it's hard to prove that it made all that much difference in practice.

In fact, some authors have suggested that the idea of using the Me 262 in the "Jabo" role was perfectly sensible. Hitler felt, with some justification in November 1943, that existing aircraft types could deal with Allied bombers. His major concern was to be able to deal with Allied amphibious landings on the beachhead where they were most vulnerable, and if there had been substantial quantities of jet bombers available that could have penetrated the thick fighter screen over the Normandy beachhead, they might have made all the difference. Who can say now?

* Sources include:

* Revision history:

v1.0 / 01 jun 01 v1.1.0 / 01 nov 01 / Changes in He 280 description. v1.1.1 / 01 dec 03 / Minor changes, comments on Me 262 project. v1.1.2 / 01 dec 05 / Review & polish. v1.1.3 / 01 may 06 / Review & polish. v1.1.4 / 01 jan 08 / Review & polish. v1.1.5 / 01 dec 09 / Review & polish. v1.1.6 / 01 nov 11 / Review & polish. v1.1.7 / 01 oct 13 / Review & polish. v1.1.8 / 01 sep 15 / Review & polish. v1.1.9 / 01 aug 17 / Review & polish. v1.2.0 / 01 jul 19 / Review & polish. v1.2.1 / 01 may 21 / Review & polish. v1.2.2 / 01 apr 23 / Review & polish. v1.2.3 / 01 apr 25 / Review & polish. (+)BACK_TO_TOP