* In the mid-1930s, Britain began programs to develop heavy bombers, with three four-engine bombers -- the Short Stirling, the Handley-Page Halifax, and the Avro Lancaster -- emerging in World War II. The Lancaster would prove the most famous of the three, but the Halifax would also be an important weapon in the conflict, being built in large quantities and seeing action all over the world. This document provides a history and description of the Halifax.

* In 1935, the British Air Ministry issued a request designated "B.1/35", specifying a new twin-engine bomber for the Royal Air Force (RAF). A number of manufacturers submitted proposals, with the Vickers firm being awarded the contract for what would emerge as the "Warwick" some years later. Handley-Page had submitted a design with the company designation of "HP 55" for B.1/35 -- but the next year, 1936, the Air Ministry issued two new requests for bombers, "B.12/36" and "B.13/36", leading to changes in company plans.

The B.12/36 requirement ultimately led to the Short Stirling, the first of the RAF's four-engine "heavies" of World War II. As for the B.13/36 requirement, design concepts from both Avro and Handley-Page were accepted for prototype development. At the outset, both these designs were to be powered by twin Rolls-Royce Vulture engines -- the Vulture being a complicated 24-cylinder water-cooled inline, essentially two vee-12 engines mated together in an "X" configuration and driving a common crankshaft. The Avro design emerged as the Manchester, which would prove notably unsuccessful, mostly thanks to the chronic unreliability of the Vulture engine. Rolls-Royce would never get the Vulture right; the Manchester was then redesigned to use four Rolls-Royce Merlin vee-12 water cooled engines, becoming the superlative Lancaster.

As for Handley-Page, company engineers rethought the HP 55 design to come up with the "HP 56", powered by twin Vultures; but before the prototype build was initiated, the deficiencies of the Vulture were becoming very apparent. Handley-Page comprehensively modified the design to use four Merlins, with the new design designated "HP 57" -- also providing a backup design using Bristol Hercules air-cooled radials, with considerations of other powerplants as well. The Air Ministry approved the Merlin-powered HP 57, with the company being awarded a contract for construction of two prototypes in September 1937. Construction began the next year.

As the first prototype neared completion, the realization grew that the machine was simply too big to operate off the relatively small airfield at the factory site at Radlett. The decision was made to perform the first flight at an unused RAF base at Bicester, with the subassemblies of the aircraft trucked over and assembled in a hangar. First flight of the HP 57 was on 25 October 1939, with company test pilot J.L. Cordes at the controls. By that time, Britain was at war with Germany.

The first prototype had fairings in place of the gun turrets, plus two-position three-blade metal de Havilland props. The Merlin installation proved troublesome, with the problems taking considerable effort to work out. The second prototype -- which did have turrets, plus floor guns and Rotol (Rolls-Bristol) constant-speed three-bladed wooden props -- followed on 18 August 1940.

Production orders had been placed in January 1938, even before the flight of the first prototype. The first production machine flew on 11 October 1940, with initial deliveries of the "Halifax B Mark I Series I" to RAF Number 35 Squadron in November 1940. After workup, in early March 1941 the Halifax performed its first combat sorties in a raid on Le Havre, followed a few days later by a night attack on Hamburg. The Halifax performed its first daylight attack on Germany in a raid on Kiel on 30 June 1941. It remained a public secret at that time, the type finally being announced to the world in July.

RAF Bomber Command's faith that defensive armament would allow bombers to perform daylight attacks without fighter escort proved overoptimistic, as proven by heavy losses. By the end of 1941 the Halifax was generally committed to night bombing operations. For the next year or more, most of the raids conducted by Bomber Command amounted to not much more than a nuisance to the Germans, the night attacks proving hopelessly inaccurate and ineffective. They accomplished little other than to force the Reich to allocate resources to air defense that could have otherwise been used for offense.

* The Halifax B.I Series I provides a baseline for the family. The B.I was a mid-wing aircraft with a twin-fin tail and powered by four Rolls-Royce Merlin X vee-12 water-cooled engines providing 855 kW (1,145 HP) each, the engines driving constant-speed three-bladed Rotol propellers -- the prop blades being made of magnesium, not wood as with the second prototype. The aircraft was built largely of metal, one of the small exceptions being fabric-covered ailerons. The Halifax was designed modularly, with a set of subassemblies being built individually and then pieced together in final assembly; the modular construction permitted more rapid construction, straightforward road transport of subassemblies, and relative ease of repair.

The wings had one-piece slotted flaps inboard and the fabric-covered ailerons outboard. Early production had wing leading-edge slats, but they were deleted early on to permit fit of barrage-balloon cable cutters. The twin-fin tail was of conventional arrangement, with rudders and elevators; tailfins were straight in the rear and triangular in the front, an arrangement distinctive of early mark Halifaxes. The bomber had tailwheel landing gear, all assemblies with single wheels, the main gear semi-retracting backward into the inboard engine nacelles and the tailwheel being fixed -- it was actually designed to be retractable, but the retracting system proved highly unreliable, and the decision was made to lock it down. Ground steering was by differential braking.

___________________________________________________________________ HANDLEY-PAGE HALIFAX B MARK I SERIES I: ___________________________________________________________________ wingspan 30.12 meters 98 feet 10 inches wing area 116 sq_meters 1,250 sq_feet length 21.36 meters 70 feet 1 inch height 6.32 meters 20 feet 9 inches empty weight 15,370 kilograms 33,860 pounds maximum bombload 5,900 kilograms 13,000 pounds MTO weight 26,310 kilograms 58,000 pounds max speed at altitude 420 KPH 260 MPH / 225 KT service ceiling 5,490 meters 18,000 feet range, max load 1,610 kilometers 1,000 MI / 870 NMI ___________________________________________________________________

Defensive armament consisted of:

Up to 5,900 kilograms (13,000 pounds) of bombs could be carried in the capacious bomb bay, which was 6.7 meters (22 feet) long; auxiliary tanks could also be fitted in the bomb bay for ferry flights or for reduced-bombload long-range missions. There was a bomb compartment inboard in each wing as well.

Typical crew was a pilot, navigator, flight engineer, radio operator, and three gunners; a second pilot could be carried for familiarization on training or as relief on long ocean patrol flights. Standard RAF Bomber Command colors for the Halifax were black on the bottom, with a disruptive pattern of brown and green on top.

BACK_TO_TOP* A total of 50 Halifax B.Mk I Series I machines was built, being followed in production by 25 "B.Mk I Series II" aircraft -- generally similar to the Series I but rated for higher gross weight, and with a number of small improvements.

The B.Mk I Series II was followed in turn by nine "B.Mk I Series III" bombers, which deleted the Vickers K guns in the beam positions in favor of a beehive-style Boulton-Paul C Mark III dorsal turret with twin 7.7-millimeter Brownings, as earlier fitted to the Lockheed Hudson. The Series III also featured 18% more fuel capacity; new Rotol propellers with a slightly increased diameter; and much-improved Merlin XX engines, with 955 kW (1,250 HP) and better altitude performance.

* Combat demonstrated that the Halifax B.Mk I left much to be desired, with about half of them lost in action up to the beginning of 1942. One of the most critical issues was improvement of defensive armament. There was design work on an "HP.58 Halifax II" with top and bottom low-profile turrets each with twin 20-millimeter cannon, the tail turret being deleted -- but it never got out of the mock-up stage.

The revised design that actually emerged was the "HP 59 Halifax B Mark II Series I", which was essentially a B.Mk I Series III with minor improvements, particularly 15% more fuel capacity. Initial flight of the B.Mk II Series I was on 11 October 1940, with introduction to service in the late summer of 1941. A few early B.Mk II Series I machines had Merlin X instead of Merlin XX engines, plus beam guns instead of the beehive dorsal turret.

* The changes in production configuration of the Halifax had led to an upward creep in weight, not entirely compensated for by the Merlin XX engine. Performance had accordingly suffered, with the B.Mk I Series 1 seen as on the edge of unacceptable. In particular, its ceiling was lower compared to the Lancaster, which made it more vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire, and in a few cases also made it the unintended target of Lancasters dropping bombs overhead.

There were experiments with cleaning up the aircraft, in particular deleting the nose turret and replacing it with a metal fairing, called a "Tempsford" or "Z-type" nose; and deleting the too-tall dorsal turret. A few were fitted with four-bladed Rotol props, with some even featuring a mix of three-bladed and four-bladed props -- say, three-bladed on the inboard engines, four-bladed on the outboard. However, four-bladed props would always be rare on Halifax bombers. Some Halifaxes were fitted with a low-profile Preston-Green belly turret with a single 12.7-millimeter (0.50-caliber) machine gun, the belly having proven a vulnerable sector for RAF bombers that Luftwaffe night-fighters had profitably exploited. The modified aircraft were designated "Halifax B.Mk I Series 1 (Special)".

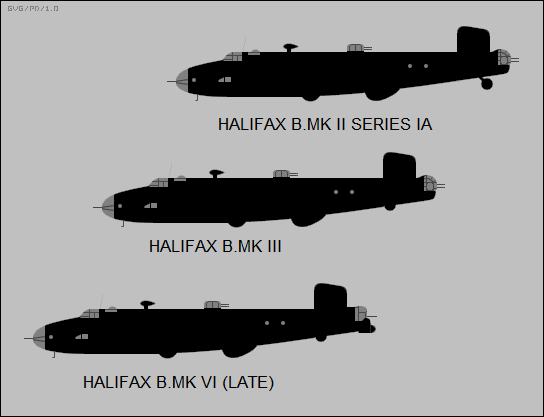

Of course, changes were introduced into production as well, resulting in the "Halifax B Mark II Series IA", modifications including:

* With the Halifax B.Mk II, production ramped up dramatically. Britain, somewhat for the lack of any better direct offensive measures to take against Hitler's Reich, was heavily committed to a strategic bombing campaign against Germany, and that meant building as many bombers as possible. The Handley-Page factories at Cricklewood and Radlett couldn't keep up with demand, but from before the war began plans had been laid for multiple sources, and four more production lines were set up:

* One of the problems encountered by ramped-up production of the Halifax was a shortage of main landing gear assemblies. As a result, Fairey and Rootes built Halifaxes with Dowty main gear assemblies instead of the default Messier main gear assemblies. For whatever reason, these machines were given the designation of "Halifax B Mark V", though they were very hard to tell from a B.Mk II; the out-of-sequence designation throws a certain amount of confusion into documenting the Halifax. 904 B.Mk V machines were built, with production including both B.Mk V Series I and B.Mk V Series IA subvariants.

* A single prototype of a "B.Mk II Series II" bomber was built by modification of a B.Mk II Series Ia featuring various small updates, but it didn't go into production. Handley-Page had something better in mind.

Ironically, although fitting the Avro Manchester with Merlin engines produced the outstanding Lancaster, for whatever reasons the Merlin was never a very good fit with the Halifax. As noted, Handley-Page engineers had considered air-cooled radial powerplants, including the 14-cylinder two-row Bristol Hercules, from early on. The Merlin was in strong demand for the Lancaster and other prominent RAF aircraft like the Spitfire, driving the development of a Hercules-powered Halifax.

After conversion of a B.Mk II Series IA (Special) machine to Hercules VI radials for trials, production moved on to the "HP 61 Halifax B Mark III" with Bristol Hercules XVI radials, providing 1,205 kW (1,615 HP), and driving three-bladed de Havilland props. The B.Mk III also featured structural reinforcements; more fuel tankage; and stronger landing gear to handle higher weights, with the tailwheel finally being made properly retractable.

Late-build Mark IIIs were also fitted with a wingspan stretch of 1.63 meters (5 feet 4 inches) to increase ceiling and range. The dee-style tailfins were standard. An H2S radar or a Preston-Green turret was fitted under the rear fuselage. The first production B.Mk III performed its initial flight on 29 August 1943, entering squadron service in late 1943. Halifax crews now had a machine that generally matched the Lancaster, with no penalty in higher loss rates. The B.Mk III was the most heavily produced Halifax variant, with 2,091 machines built.

___________________________________________________________________ HANDLEY-PAGE HALIFAX B MARK III (EXTENDED WINGS): ___________________________________________________________________ wingspan 31.75 meters 104 feet 2 inches wing area 118.4 sq_meters 1,275 sq_feet length 21.82 meters 71 feet 7 inches height 6.32 meters 20 feet 9 inches empty weight 17,345 kilograms 38,240 pounds maximum bombload 5,900 kilograms 13,000 pounds MTO weight 29,485 kilograms 65,000 pounds max speed at altitude 455 KPH 280 MPH / 245 KT service ceiling 7,315 meters 24,000 feet range, max load 1,660 kilometers 1,030 MI / 895 NMI ___________________________________________________________________

* Although a prototype conversion was performed on a B.Mk II for a "Halifax Mark IV" with Merlin engines, plus other changes such as dual wheels on each main gear assembly, events passed it by, and the B.Mk III was actually followed by the "B Mark VI", which featured Hercules 100 radials providing 1,250 kW (1,675 HP) take-off power, plus engine intake filters and a pressurized fuel system -- the changes being mostly intended to support tropical operations in the Far East. They were otherwise similar to the B.Mk III in airframe configuration and equipment fit. Late production machines had a Boulton-Paul D.Mk II tail turret with twin 12.7-millimeter Browning machine guns and "Village Inn" aiming radar.

The "B Mark VII" was effectively the same as B.Mk VI, except that it reverted to Hercules XVI engines due to a shortfall in Hercules 100 production. A total of 643 B.Mk.VI and 160 B.Mk VII machines was built. 64 were transferred to France after the war, and 8 were provided to Pakistan.

* During the war, many wondered why the Halifax remained in production when the Lancaster seemed the better bomber, but with the introduction of the B.Mk III, there wasn't that much to distinguish the two in terms of range, ceiling, and speed. The Halifax did have a somewhat smaller bombload, about 85% that of the Lancaster, and the ultimate loss rate was higher -- about one Halifax per 21 sorties, versus about one Lancaster per 27 sorties. However, this statistic was skewed by high losses of Halifaxes in the early days -- the Halifax was in combat service about a year before the Lancaster became a real force -- and in maturity, the odds of surviving being shot down in Halifax were almost twice as great as they were for a Lancaster. While the ultimate full load of bombs carried by the Halifax during the war was only about a third that carried by the Lancaster, it was still more than dropped by all other RAF bombers combined.

BACK_TO_TOP* At its peak, the Halifax equipped 34 RAF Bomber Command squadrons in Europe, plus four in the Middle East, along with more squadrons in the Far East, which were built up after the surrender of Germany for the final assault on the Japanese.

The Halifax was overshadowed by the Lancaster as a bomber, but the capacious fuselage of the Halifax made it suitable for other duties -- though the fact that Bomber Command couldn't get Lancasters fast enough for bombing operations also factored into the preference for using the Halifax in alternate roles. One such alternate role was electronic warfare, with a number of conversions of B.Mk III machines to such "bomber support (BS)" configurations. They generally looked much like the bomber configuration, other than sporting a litter of additional antennas. There were various configurations, featuring such kit as:

Configurations were generally optimized for ELINT, radar jamming, or communications channel jamming, though the electronic equipment fits tended to be variable.

* RAF's Coastal Command was a user of the Halifax as well, operating conversions of various Halifax bomber variants:

Halifaxes were converted to serve in the weather reconnaissance role for both Bomber Command and Coastal Command, with conversions including the "Met.Mk V", "Met.Mk III", and "Met.Mk VI". The meteorological Halifaxes were fitted with weather instrumentation and an associated operator's station. These aircraft generally retained full armament, since they ranged widely alone and sometimes over hostile territory. From midwar, the GR and Met Halifaxes were painted dark sea gray on top, white on the bottom.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Halifax also proved useful as a paratroop transport / glider tug, as well as an airliner / cargolifter. Minimally modified B.Mk II Series 1 were initially put to this use in late 1941, being employed to support European resistance operations via the British "Special Operations Executive (SOE)". Bomber Command only grudgingly spared aircraft for SOE, particularly since there was a perception that the SOE wasn't a good use of resources -- a view often supported by modern historians, who suggest that the resources pumped by the Western Allies into resistance groups generally created forces who didn't cause the Germans serious trouble, but were often enthusiastic at fighting among themselves.

However, SOE was one of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill's pet projects and it couldn't simply be shrugged off. The result was conversion of B.Mk II Series 1 machines to a "Special" configuration for SOE, with:

Various tweaks were made to enhance streamlining. The tail turret was retained. These machines were eventually fitted with the Gee radio navigation system, as well as "Rebecca" -- a "radar beacon" system that would interrogate a "Eureka" ground unit set up by a resistance group to nail down its location. A number of B.Mk V Series 1 machines were converted to a similar specification.

British Airborne Forces used the "A.Mk V" -- generally similar to the B.Mk V (Special) machines used by SOE, except for the addition of a glider tow hookup under the tail. They performed their first combat operation on 9 November 1942, when two A.Mk V tugs hauled two Horsa gliders loaded with Norwegian troops to Norway to attack German-controlled heavy water production facilities. The attack was a fiasco, with one tug lost and both gliders crash-landing. The Germans captured the Norwegian survivors; they were executed, even though they were in uniform, as per a secret order issued by Hitler the month before that directed the killing of commando troops.

The A.Mk V was followed by the "A.Mk III", "A.Mk VI", and "A.Mk VII" paratroop / glider tug conversions. The need for the Halifax in the paratroop role was seen as important enough to justify new-build construction of the A.Mk III, with at least 30 built, and the A.Mk VII, with at least 228 built. The A.Mk VII machines could be easily reconfigured back to bomber operation, though it was rarely done.

Airliner / cargolift conversions for RAF Transport Command included the "C.Mk V", "C.Mk III", "C.Mk VI", and "C.Mk VII", characterized by removeable cargo panniers plugged into the bomb bay. They were comparable in many ways to cargo-hauler configurations of the B-24 Liberator. Typically they could carry eight passengers or nine stretchers.

* Most of the bomber Halifaxes were retired with the end of the war, but the coastal patrol machines served on for several more years. There were actually two new-build variants produced, if briefly, in the postwar period.

Following studies for the development of a Halifax-derived "HP 64" dedicated cargolift transport machine with a new fuselage, Handley-Page instead focused on modification of the B.Mk VI, with conversion from a B.Mk VI performing trials in the spring of 1945. That led to production of 98 "HP 70 C.Mk VIII" cargo-transport machines, with no armament -- the tail turret was faired over -- plus a paratroop door and provision for a belly pannier.

The C.Mk VIII was mostly operated by the Free Poles, but since the Free Poland operation didn't have a future in the postwar period, neither did the Free Pole squadrons. Most were then operated with some minor civilianized modifications for a few years by BOAC, with the type participating in the Berlin Airlift from 1948. Along with the standard belly pannier, they could be fitted with an alternate high-capacity pannier, less streamlined but capable of carrying bulkier items.

A dozen of these aircraft were modified to a relatively tidy airliner configuration, featuring rectangular passenger windows and comfortable accommodations for ten passengers, and flown by BOAC as the "HP 70 Halton". The C.Mk VIII was also operated by some other civil organizations, but it was out of service by the early 1950s.

Boulton-Paul built 145 "HP 71 Halifax A.Mk IX" paratroop transports, derived from the B.Mk III and powered by Hercules XVI engines. They had a paratroop door and could carry 16 paratroopers, with folding bench-type seats on both sides of the cabin; they also had a glider tow attachment under the tail and could be fitted with a belly pannier, but it seems that was rarely if ever done -- though sometimes they paradropped jeeps or gear carried on pallets under the bomb bay. They were armed with a 12.7-millimeter Browning machine gun in the nose and a Boulton-Paul D.Mk II tail turret with twin 12.7-millimeter guns, as fitted to late-build B.Mk VI bombers.

The A.Mk IX was used mostly for training for a few years after the war, though three were used for meteorological duties. A few A.Mk IX machines also served in the Berlin Airlift. It was out of British service by the early 1950s, but nine ended up in Egyptian hands and struggled on for a few more years until they were grounded by parts shortages. The last Halifaxes were phased out of service in the mid-1950s. While at least three Halifaxes survive as museum displays, none remain flying.

* A total of 6,104 Halifaxes were built. Variants included:

Sources are very fuzzy on Halifax production subtotals, and so the numbers cited here are only approximate.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Halifax is not over-documented, and aside from some comments here and there scrounged up online, there's really only one source for this document:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 oct 10 v1.0.1 / 01 sep 12 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 aug 14 / Review & polish. v1.0.3 / 01 jul 16 / Review & polish. v1.0.4 / 01 jun 18 / Review & polish. v1.0.5 / 01 apr 20 / Review & polish. v1.0.6 / 01 feb 22 / Review & polish. v1.0.7 / 01 jan 24 / Review & polish. (+)BACK_TO_TOP