* The notion of the "tail first" or "canard" aircraft goes back to the dawn of flight, but by the time of World War II it was a neglected concept. A number of prototypes of canard combat aircraft were actually built by a number of combatants in the conflict, though none of them went into production. This document provides a survey of these canard combat aircraft.

* The Italians were the first of the participants in World War II to build a canard combat aircraft, the SAI-Ambrosini "S.S.4". Italian aircraft engineer Sergio Steffanutti had become interested in canard aircraft in the 1930s, developing a lightweight flight demonstrator designated the "S.S.2" that performed its initial flight in 1935. Two S.S.2 prototypes were built, with the second later being converted into a two-seater. The S.S.2 seemed promising to the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force), and so Steffanutti worked with manufacturing firm Societa Aeronautica Italia Ing Ambrosini to scale up the design into a combat fighter, which Steffanutti labeled the "S.S.4".

A single prototype was built, performing its initial flight with test pilot Ambrogio Colombo at the controls on 7 March 1939, months before the outbreak of war. The S.S.4 was a neat, all-metal aircraft with a retro-future science-fiction appearance, featuring a foreplane on the nose, a rear low-mounted wing with a swept leading edge, a tailfin in the middle of each wing, and retractable tricycle landing gear.

The machine was powered by an Isotta Fraschini Asso IX RC.40 liquid-cooled vee-12 engine with 175 kW (960 HP), mounted behind the cockpit and driving a three-bladed variable-pitch pusher propeller. There was an engine inlet scoop on either side of the fuselage, just behind the cockpit. Sources differ on the armament configuration: some sources claim two 20-millimeter cannon and a single 30-millimeter cannon, but that was unusually heavy armament for an Italian fighter of the time, and a more plausible fit was two 12.7-millimeter Breda machine guns and a single 20-millimeter cannon, all fitted in the nose. Pictures show the Breda machine guns fitted, but the port for the cannon left empty.

___________________________________________________________________

SAI-AMBROSINI S.S.4:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

12.32 meters (40 feet 5 inches)

wing area:

17.5 sq_meters (188.4 sq_feet)

length:

6.74 meters (22 feet 2 inches)

height:

2.48 meters (8 feet 2 inches)

empty weight:

1,800 kilograms (3,968 pounds)

normal loaded weight:

2,446 kilograms (5,392 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

540 KPH (335 MPH / 290 KT)

___________________________________________________________________

The program came to an abrupt end the next day, 8 March, when Colombo took the machine up for a second flight. An aileron malfunctioned and Colombo tried to set the machine down in available open space; he ran into a tree and was killed, with the aircraft totaled. There was some consideration of building a second prototype, but it didn't happen. The initial flight had not demonstrated any particular superiority to fighter aircraft of conventional configuration, and there had been increasing misgivings about the project anyway. How was the pilot to bail out, for example, without getting chopped to pieces by the rear-mounted propeller? There were also concerns about engine cooling, rearward view, and that the engine would crush the pilot if the aircraft ran into something on the ground. Steffanutti went on to develop lightweight fighter aircraft of conventional configuration.

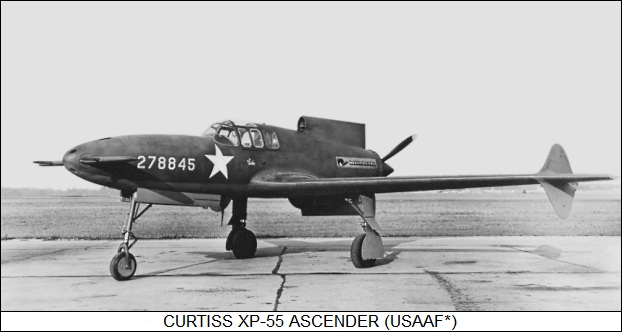

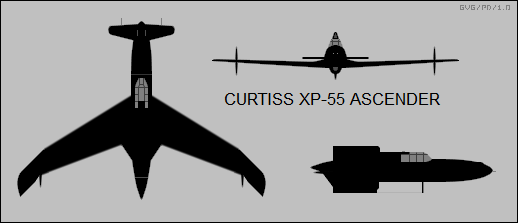

BACK_TO_TOP* In the fall of 1939, the US Army Air Corps (USAAC) issued a request for proposals for an advanced piston-powered fighter that would outmatch any others currently in service. The request specified that "unconventional configurations" would be acceptable, and the manufacturers took the Air Corps at their word. The result would be three of the most unconventional aircraft developed by the US during World War II, all pusher-prop fighters: the twin-boom Vultee "XP-54", the tailless Northrop "XP-56", and a canard design, the Curtiss-Wright "XP-55".

The Curtiss machine was designed by a team under Don Berlin and was originally known by the company code of "CW-24". It was to have swept rear wings with wingtip tailplanes; what would be later called "all-moving foreplanes" up front; and a retractable tricycle undercarriage. At the outset, the plan was to fit the CW-24 with the Pratt & Whitney (P&W) X-1800-A3G (H-2600) liquid-cooled inline engine, then in development, mounted behind the pilot's cockpit. Estimated top speed was to be an impressive 815 KPH (505 MPH).

The Air Corps liked the concept enough to award funding in the spring of 1940 for preliminary development and construction of a wind tunnel model, with the aircraft to be given the service designation of "P-55". USAAC brass were not that impressed by the results of the subsequent wind tunnel tests, so Curtiss engineers decided to build a full-scale flying demonstrator, the "CW-24B".

The CW-24B featured a fuselage made of steel tubing covered with fabric, a wooden wing, fixed undercarriage with spats, and was powered by a Menasco C68-5 four-cylinder inverted-inline engine providing 205 kW (275 HP). After being rolled out, the CW-24B was transported from the Curtiss plant in Saint Louis to the Army Air Forces flight test center at Muroc Dry Lake, later Edwards Air Force Base, in California for its initial flight on 2 December 1941. (The Army Air Corps had been superseded by the US Army Air Forces, or USAAF, in June 1941.)

Top speed was only 290 KPH (180 MPH), but that was to be expected given the light engine. Early flights exhibited some directional instability, which was corrected by enlarging the tailfins, moving them farther out on the wing, and adding fins to the top and bottom of the rear fuselage. Flight testing continued at Muroc into May 1942. The demonstrator was then passed on to the US National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) at Langley Field in Virginia for further trials.

The test flights of the CW-24B indicated the design had merit, and so in July 1942 the USAAF awarded a contract to Curtiss for three prototypes, to be designated "XP-55". The P&W X-1800 engine program was running into trouble at the time, and in fact it would be eventually given the axe, and so the decision was made to use the Allison V-1710-F23R engine, basically the same engine as used on the Lockheed P-38 Lightning but modified for pusher mounting, with 950 kW (1,275 HP). The engine was to drive a three-bladed propeller, though a contra-rotating propeller system had been considered. Armament was initially to be two 20-millimeter cannon and two Browning 12.7-millimeter (0.50-caliber) M2 machine guns, but the decision was made to use four M2 machine guns instead.

The initial XP-55 prototype performed its first flight from the USAAF's Scott Field in Saint Louis, not far from the Curtiss plant, on 19 July 1943, with Curtiss test pilot J. Harvey Gray at the controls. The take-off run proved excessive and so the flight surfaces were appropriately modified. The aircraft was given the name of "Ascender", it seems as a joke: "Ass-Ender". It seems that it was also, appropriately for a canard, nicknamed the "Flying Goose". Unfortunately, the initial prototype was lost on 15 November 1943, when Gray was performing stall tests and got into a stall he couldn't recover from. Gray bailed out, but the aircraft was a loss.

The second XP-55 prototype was in an advanced state of construction at the time of the accident and it was impossible to thoroughly redesign it to ensure the accident wasn't repeated, though some tweaks were made. The second XP-55 performed its initial flight on 9 January 1944, with careful flight limits being observed to avoid the accident that had destroyed the first machine.

The third prototype followed on 25 April 1944. It featured full armament of four machine guns, as well as modifications to deal with the stall problem, most significantly wingtip extensions. The fixes did help with the problem, but the XP-55 still suffered from poor stall recovery and a lack of stall warning, meaning it went into a stall abruptly. An artificial stall warning system was added. The second prototype was updated to the same configuration as the third, but further flight tests into the fall of 1944 still demonstrated unsatisfactory stall performance.

___________________________________________________________________

CURTISS XP-55 ASCENDER:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

13.56 meters (44 feet 6 inches)

wing area:

21.83 sq_meters (235 sq_feet)

length:

9.02 meters (29 feet 7 inches)

height:

3.05 meters (10 feet)

empty weight:

2,882 kilograms (6,354 pounds)

MTO weight:

3,324 kilograms (7,330 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

630 KPH (390 MPH / 340 KT)

service ceiling:

10,550 meters (34,600 feet)

range:

790 kilometers (490 MI / 425 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

By that time, jet fighters were seen as the way of the future. Curtiss did consider a jet-powered variant, the "CW-24C", but after the extended development and ongoing difficulties, the XP-55 didn't seem particularly promising, and so the USAAF canceled the program. The third prototype was lost in a crash during an airshow at Wright Field in Ohio on 27 May 1945; the pilot, USAAF Captain William C. Glasgow, was killed, along with a motorist on the ground. The second prototype survives today as an exhibit at the Kalamazoo AirZoo in Kalamazoo, Michigan. What happened to the CW-24B is unclear; little mention is made of it, and it was likely scrapped.

* The story of the Curtiss company during World War II is a generally unhappy one, with the company unable to keep up with advances in aviation technology and producing aircraft such as the SB2C Helldiver that were plagued with difficulties. Companies have their own specific cultures, generally traceable to management policy, and it appears that the Curtiss company culture was unable to attract or keep the best talent, and get things done in an efficient fashion. The XP-55 Ascender was an innovative and interesting aircraft, but Curtiss was simply unable to make it into a winner.

BACK_TO_TOP* Even as the XP-55 was in flight to oblivion, an Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) officer named Captain Tsurano Masaoki, of the IJN Technical Staff, was considering a fighter aircraft of similar configuration. After performing some preliminary studies, the First Naval Air Technical Arsenal designed an all-wood glider demonstrator with fixed landing gear, designated the "MXY6". Three were built by Chigasaki Seizo KK for the IJN, performing initial test flights in the fall of 1943. One was later fitted with a small four-cylinder air-cooled engine.

The demonstrator flights having proven satisfactory, the IJN awarded a contract to Kyushu Hikoki KK to build the "Type Otsu (B) Interceptor Fighter". Kyushu had never built such an advanced, high-performance aircraft, but the company was relatively unburdened by production commitments at the time and it was the resource that could be spared. A team from the First Naval Air Technical Arsenal under Captain Tsurano was assigned to provide technical supervision on the project. Formal work on the "J7W1 Shinden (Thunder & Lightning)", as it was designated, began in June 1944, with the first of two prototypes rolled out ten months later -- a remarkable feat considering that Japanese industry was under gradually increasing pressure from blockade and strategic bombing through that interval.

The general configuration of the Shinden was along the lines of that of the S.S.4 and XP-55: a low-wing pusher canard aircraft, with tricycle landing gear and a tailfin mounted in each wing. It was powered by a Mitsubishi MK9D (Ha-43) 18-cylinder two-row radial engine providing 1,590 kW (2,130 HP), driving a six-bladed propeller. Armament was four 30-millimeter Type 5 cannon mounted in the nose, with either two 60-kilogram (132-pound) or four 30-kilogram (66-pound) bombs carried under the wings. Interesting features were small retractable bumper wheels at the base of each tailfin and large slanted air intakes just to the rear of the cockpit.

___________________________________________________________________

KYUSHU J7W1 SHINDEN:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

11.11 meters (36 feet 6 inches)

wing area:

20.5 sq_meters (220.6 sq_feet)

length:

9.66 meters (31 feet 8 inches)

height:

3.92 meters (12 feet 10 inches)

empty weight:

3,645 kilograms (7,639 pounds)

normal loaded weight:

4,928 kilograms (10,854 pounds)

MTO weight:

5,228 kilograms (11,526 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

750 KPH (465 MPH / 405 KT)

service ceiling:

12,000 meters (39,370 feet)

range:

830 kilometers (590 MI / 460 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Getting the machine in fully flightworthy condition did prove difficult, and the first prototype didn't perform its initial flight until 3 August 1945, with Captain Tsurano at the controls of his brainchild. Some deficiencies were noted, but it seems they could have been corrected. Unfortunately for the Shinden, on 15 August the Emperor announced that Japan would surrender to the Allies. The second prototype had been completed by that time but not flown. The IJN had set up plans for full production even before the initial flight of the Shinden, but the idea was a desperate fantasy. Tsurano had also planned a jet-powered variant, the "J7W2", from the outset, to be fitted with an Ne-130 turbojet with 8.83 kN (900 kgp / 1,984 lbf) thrust, but that didn't happen either.

One of the Shinden prototypes -- which one is unclear, sources differ -- was hauled off to America by US Navy intelligence for evaluation, though it was apparently not flown. It ended up in the hands of the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, though it has not been restored yet and remains in stockpile. What happened to the other Shinden is a mystery.

BACK_TO_TOP* In 1941, Miles Aircraft of the UK conducted a preliminary investigation into a pusher-prop carrier-based fighter with a "twin wing" configuration. Most looking at the concept drawings would have called it a canard, but the foreplane was unusually large, and was used as both a lifting and control surface; some like to fudge and call it a "twin wing canard" configuration. The arrangement gave a good forward view, a major plus in carrier operations, and the twin wing helped reduce span of the main wing, eliminating the need for heavy and complicated wing folding kit. The twin wing also made the configuration unusually insensitive to center-of-gravity variations.

Miles engineers were somewhat reluctant to try to sell such an unorthodox concept without having backed it up, so a demonstrator, the "M.35", was built. Apparently Miles had a really crackerjack engineering and prototype construction team, since the demonstrator was completed in only six weeks after the go-ahead, performing its first flight on 1 May 1942. It was named the "Libellula", after the formal name for the dragonfly family.

The M.35 had a foreplane mounted high behind the cockpit; a main wing with swept outer panels at the rear; tailfins mounted on the main wingtips; a pusher prop; and fixed tricycle landing gear. The foreplane had almost the same span as the rear wing, though the rear wing had over twice as much area. It was powered by a de Havilland Gipsy Major four-cylinder inverted inline engine with 95 kW (130 HP). Details of performance are unclear, but given that the aircraft was strictly an aerodynamic demonstrator and underpowered at that, it seems likely that endurance was relatively short and speed not much greater than, say, 240 KPH (150 MPH).

___________________________________________________________________

MILES M.35:

___________________________________________________________________

front wingspan:

6.1 meters (20 feet)

front wing area:

4 sq_meters (45 sq_feet)

rear wingspan:

6.32 meters (20 feet 5 inches)

rear wing area:

8.3 sq_meters (90 sq_feet)

length:

6.19 meters (20 feet 4 inches)

height:

2.06 meters (6 feet 9 inches)

empty weight:

660 kilograms (1,455 pounds)

normal loaded weight:

840 kilograms (1,850 pounds)

___________________________________________________________________

The M.35 demonstrated that there was nothing wrong with the idea, though some longitudinal instability was noted. Miles then submitted the concept to the Admiralty and the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP); nothing came of it.

However, the M.35 demonstrator seemed so promising that Miles had gone forward without a pause on development of a fast medium bomber, under the general cover of Air Ministry specification B.11/41, issued to encourage development of a successor to the de Havilland Mosquito. The bomber was given the designation of "M.39" and was to be powered by three Power Jets W.2/500 centrifugal-flow turbojets or equivalent powerplants, giving a top speed of 800 KPH (500 MPH). Since the turbojets might not be available at the outset, twin piston engines -- Rolls-Royce Merlins were seen as the preferred powerplants -- were considered as an alternative, with the aircraft's configuration allowing considerable commonality between the jet and piston versions.

A 5/9ths-scale demonstrator, the "M.39B", was built to support the bomber development effort, with the demonstrator performing its initial flight on 22 July 1943. It was powered by twin uprated Gipsy Major engines with 105 kW (140 HP) each, with each engine mounted in its own nacelle inboard on the wing, driving in tractor configuration. Because of the engine configuration, the foreplane was low mounted while the rear wing was high mounted, to give the props ground clearance. The M.39B also differed from the M.35 in featuring retractable landing gear and a central tailfin along with the wingtip tailfins, it seems to correct the directional instability problems.

___________________________________________________________________

MILES M.39B:

___________________________________________________________________

front wingspan:

7.6 meters (25 feet)

front wing area:

6.64 sq_meters (61.7 sq_feet)

rear wingspan:

11.43 meters (37 feet 6 inches)

rear wing area:

20.16 sq_meters (187.5 sq_feet)

length:

6.76 meters (22 feet 2 inches)

height:

2.82 meters (9 feet 3 inches)

empty weight:

1,091 kilograms (2,405 pounds)

normal loaded weight:

1,270 kilograms (2,800 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

165 KPH (100 MPH / 90 KT)

___________________________________________________________________

Flight trials of the M.39B went well, and in September 1943 the MAP awarded Miles a contract for a prototype, with the award also paying off Miles for the M.39B demonstrator. That was as far as it went, however, since official interest faded out and the M.39 prototype was never built. It seemed like a promising concept, but it just got lost in the shuffle.

* Other British aircraft manufacturers also considered canard designs. Boulton-Paul came up with a single-seat, single-engine canard attack fighter concept designated the "P.100", but it never got off paper. In 1943, Vickers drew up a set of possible configurations for a super-heavy bomber, in the class of the later US Convair B-36. Some of the concepts featured a canard configuration, with six piston engines and bristling with defensive gun turrets. They were very amusing ideas, but never much more than back-of-the-envelope exercises.

BACK_TO_TOP* The German Henschel aircraft firm toyed with canard designs, though none of them flew. The "P.75" was conceived in 1941; it was a sleek, futuristic fighter that was to have been armed with four MK 108 30-millimeter cannon in the nose, and powered by a Daimler-Benz DB 610 engine driving contraprops. The tailfin was placed on the bottom instead of the top of the aircraft to keep the props from divoting the runway on take-off.

The DB 610 was basically two DB 605 vee-12 engines ganged together. The DB 610 was being developed for the Heinkel He 177 bomber, and proved a major stumbling block in the He 177 development program; the engine had an unfortunate tendency to catch fire, with the He 177 demonstrating the odd inclination of German engineering to be too clever for its own good. Later the P.75 was to be fitted with the DB 613 engine, though whether it would have been an improvement is unclear -- it consisted of twin ganged DB 603 vee-twelve engines.

___________________________________________________________________

HENSCHEL P.75

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

11.3 meters (37 feet 1 inch)

wing area:

28.4 sq_meters (305.7 sq_feet)

length:

12.2 meters (40 feet)

height:

4.3 meters (14 feet 1 inch)

MTO weight:

7,500 kilograms (16,535 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

790 KPH (490 MPH / 425 KT)

service ceiling:

12,000 meters (39,370 feet)

___________________________________________________________________

The P.75 never got beyond wind tunnel models. Henschel also came up with a design for a canard fast bomber, the "P.87", which was to be driven by a single Daimler-Benz DB 610 engine driving a pusher contraprop. It also never amounted to more than a back-of-the envelope design. It seems plausible that "paper plane" canard designs were considered by the Soviets and other combatants, but if so they didn't fly and information on them is lacking.

BACK_TO_TOP* In modern times, canard aircraft are not particularly unusual. Several leading-edge jet fighters, such as the Swedish SAAB JAS 39 Gripen, use the configuration -- though these "canard-delta" machines seem to be more rooted in the notion of attaching a foreplane to a delta-wing supersonic jet than any descendants of the canard concepts of World War II.

However, mostly thanks to the efforts of aviation innovator Burt Rutan, pusher-prop canards did become familiar in the sport aviation market -- for a time at least. They didn't have clear advantage over the tractor-prop configuration, and in the end couldn't compete. They're still around, but rarely seen.

* Sources include:

The online Wikipedia and writings by aviation enthusiast Joe Baugher were also consulted.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 dec 08 v1.0.1 / 01 nov 10 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 oct 12 / Review & polish. v1.0.3 / 01 sep 14 / Review & polish. v1.0.4 / 01 aug 16 / Review & polish. v1.0.5 / 01 jul 18 / Review & polish. v1.0.6 / 01 may 20 / Review & polish. v1.0.7 / 01 mar 22 / Review & polish. v1.0.8 / 01 feb 28 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP