* Considerable thought had gone into building the A-10, and considerable thought was put into making the best use of such a unique aircraft in its planned combat environment, over the forests and hills of Central Europe. Hog pilots acquired skills and tactics that they believed would allow them to even the odds against Soviet armored formations.

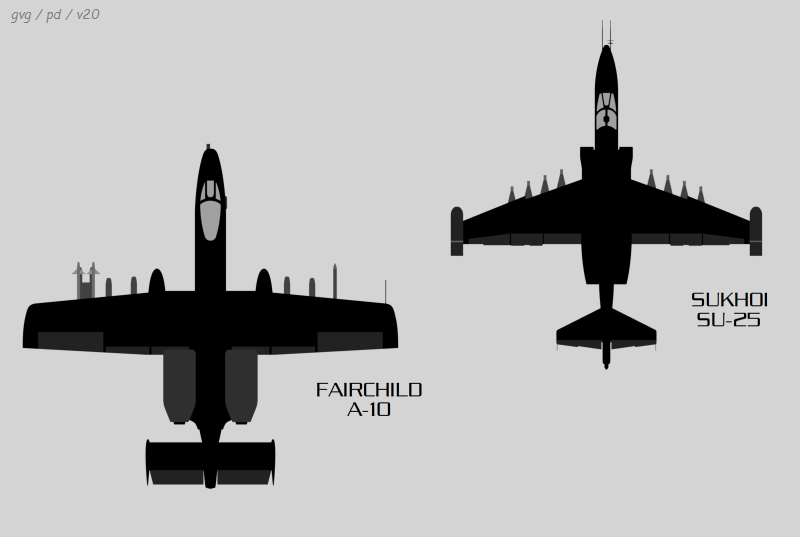

Still, the Air Force had its ambiguities about the A-10 and by the end of the 1980s it didn't seem to have much of a future. Combat would then demonstrate the value of the Hog, and it would serve well into the 21st century. This chapter provides a service history of the A-10, and also a comparison of the type against its Soviet-Russian counterpart, the Sukhoi Su-25.

* The USAF accepted the 100th production A-10 at a special ceremony on 3 April 1978, attended by two retired USAF officers: Brigadier General Francis "Gabby" Gabreski and Colonel Robert S. Johnson, both aces who had flown the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt in World War II. By that time, the Air Force could look back on the program with well-earned satisfaction. It had been conducted competently and efficiently, with program officials overcoming all technical and political obstacles, with a reliable and very-well-tested product delivered generally on schedule and within budget.

Early on the Air Force, having got their hands on a machine for which there was no precise precedent in the service's history -- though the A-1 Skyraider was something of an approximation -- conscientiously worked with the Army to figure out how to make the best use of the A-10. During 1977 the two services worked on a concept known as "Joint Attack Weapons Systems (JAWS)", performing preliminary experiments at Fort Benning, Georgia, in September 1977, followed by a full-blown military exercise at Fort Hunter Liggett in California in November of that year.

The primary mission of the Warthog was to engage and destroy enemy armor on the battlefield. The main threat against the A-10 was the Soviet ZSU-23-4 "Shilka" radar-guided, quadruple mount 23-millimeter, tracked antiaircraft gun system, which was the predominant short-range air-defense weapon of the Red Army and Soviet client states. The Shilka was backed up by the Soviet SA-8 Gecko wheeled SAM system, which took care of threats at longer ranges. The Soviet military was also traditionally big on tactical air support, and an A-10 pilot was very likely to encounter MiG-23 Flogger fighters operating in support of Red Army field units.

The Air Force understood from the outset that the Warthog would operate close to the ground, making use of terrain features for protection, then performing a pop-up or "bunt-up" maneuver to attack enemy formations with cannon and other weapons, making use of its extreme agility and tossing out flares and chaff to blind enemy defenses. What the JAWS exercises demonstrated was that the Warthog was most effective when used in combination with other Army assets, including artillery and particularly helicopter gunships, which at the time meant the Bell AH-1 Cobra but would later mean the Hughes AH-64 Apache. Studies demonstrated that Hogs and gunships working together were far more deadly than either working by themselves.

The A-10 could operate above the treetops at about 30 meters (100 feet) or so, the helicopters below the treetops; between them, they could spot and destroy the air-defense assets of enemy formations. That task done, they could smash everything else with relative impunity. Coordination between A-10s and gunships had to be coordinated by forward air controllers (FAC) on the ground or in the air, operating as "traffic cops" to direct the strikes.

As far as the MiG-23 was concerned, Hog pilots were generally more worried about ground defenses. A MiG-23 pilot would find a jinking A-10 a hard target to get a bead on; the Warthog's flares could frustrate heat-seeking missiles; the target's low altitude, chaff, and jammer pod could similarly frustrate radar-guided missiles; and, last but not least, a fighter pilot that tried to press in on a Hog too close might well get a devastating burst of 30-millimeter cannon fire in the face. Sidewinders were apparently not often carried in the early days, but they would eventually be added to the equation as well. Taking on a Hog was not like picking off a sitting duck, it was more like reaching down a hole to grab a badger: it might not move very fast, but it could bite really hard.

* The lessons of the JAWS exercises were codified in a "Joint Air Attack Team (JAAT)" manual that was to become the "bible" for Hog pilots. There was still skepticism about the type among NATO forces when it was deployed to Europe beginning in 1979. It was all very well and good to pick off tanks sitting more or less passively in the Nevada or California desert in bright sunny weather, but trying to nail targets that were shooting back in damp northern European murk was another question entirely. The fact that the Hog didn't carry all-weather nav-attack gear made the question very pertinent.

Actually, as mentioned the weather issue had been addressed in the aircraft specifications: the A-10 was designed to fly under the cloud ceiling, and simple cloudy or rainy weather was no particular obstacle. Night operations were a challenge, but in principle the LANTIRN pod system was supposed to deal with that issue. Unfortunately, development of LANTIRN kept slipping out.

Still, the lethality of the A-10 was hard to argue with. The fact that it could operate off of short strips not far off the battle line meant that it could respond quickly to requests for fire support. A-10s in Germany practiced dispersal to concealed forward bases hidden in the woods, flying off small strips or chunks of Autobahn. Once in the battle area, A-10s could stay there as long as necessary. The aircraft was very reliable, with a high availability rate; easily maintained and turned around quickly between sorties; and was much cheaper to operate than a fast-mover strike fighter.

Hog pilots had few doubts about their machine. It wasn't fast, fighter pilots joked that Hog pilots had to worry about birdstrikes from the rear, but it handled well and was very agile. The good handling made it pleasant to fly -- pilots called it the "Big Tweet", a comparison to the docile if noisy Cessna T-37 "Tweet" trainer -- while the agility gave allowed a pilot to test his abilities to the limit. Pilots say it handles as though it were smaller than it really is, which can be dangerously deceptive when operating close to the ground. The major problem with flying the Hog is that the engines throttle up slowly and the airframe is draggy, meaning it does not accelerate rapidly. Rapid acceleration is very desireable after making an attack pass and then departing the immediate target area: "Do unto others -- then split."

While the YA-10As had been painted light blue or gray to blend in with the sky, the consensus finally arrived that they would be better off painted to camouflage themselves against the ground in order to spoof hostile fighters. There were some unusual experiments with leopard-spotted camouflage schemes during the JAWS experiments -- but after trying out various other options, the decision was made to paint Hogs in a disruptive pattern of dark green and dark gray, known as "Charcoal Lizard".

* A total of 703 full-production A-10s was built in all up to early 1984, not counting the two YA-10As and the ten evaluation machines. The end of A-10 production put Fairchild in a difficult financial position. Fairchild had tried to sell the A-10 on the export market, but with little luck. The company leased a Hog from the USAF in 1976 to show at the Farnborough air show in the UK and got little more than curious interest. It was an unusual machine, but few thought it useful to their own requirements; the US government also had a ban on the export of uranium-core ammunition, which complicated the sales pitch.

The company sent an A-10 to Paris the next year, 1977, and things went much worse, the pilot smashing the machine into the ground while performing a loop on the opening day of the show. The pilot, Sam Nelson, was killed. The company made a final sales push in 1982 and 1983, proposing configurations with more modern and powerful engines, but there were no takers. The firm received a final blow with the cancellation of their troubled T-46 trainer effort, and the company finally closed its doors in early 1987. The A-10 was the very last Republic aircraft to reach operational service. Grumman bought up rights to and engineering resources for the aircraft in late 1987.

BACK_TO_TOP* Although the A-10 was exactly what the USAF had specified and met that specification well, by the late 1980s, as far as the USAF was concerned, the writing was on the wall for the Warthog. It was the old Air Force ambivalence about the CAS mission coming to the surface again. To be sure, the long-running friction between the Air Force and the Army over CAS is not a simple scenario of the white hats versus the black hats. While the military has its fair share of dumb SOBs, it also has its fair share of sensible and competent people, and the CAS issue was one in which good people could differ: What you see depends on where you stand.

One perfectly valid factor in the USAF's uncertainty about the Warthog was the need to have aircraft that could perform more than one mission. The A-10 was optimized for the close-support mission to the extent that wasn't all that useful for any other mission. The Air Force had to be able to perform a wide range of missions, and the service naturally preferred multirole aircraft that could perform those varied missions.

The irony of this was that the A-10 had evolved at a time when the service was disenchanted with the multirole concept and had been trying to develop specific-purpose aircraft. In the interim, however, technology improved, and new aircraft demonstrated that they could do very well in both the air-combat and strike roles. Although the Air Force had its misgivings about the General Dynamics F-16 early on as well, it evolved into a multirole aircraft, something the A-10 was not. The USAF needed to limit the numbers of aircraft types in its inventory, not merely to simplify logistics and training, but because higher production volumes for one type of aircraft meant lower unit cost.

The F-16 looked much better to the blue-suit brass than the A-10, and it wasn't just snobbery. The Air Force had cut off production of the A-10 when the powers-that-be had determined the numbers were adequate to support the CAS mission, and then focused on building up numbers of F-16s. In another irony, it was the reliability and high availability rate of the A-10 that also convinced the Air Force to limit its production. Simply put, it was there when it was needed -- why buy more? Again, it was hard to argue against such logic.

A more specific factor in the USAF's uneasiness with the Hog was that tactical air defenses were continuously improving. The A-10 had been designed to soak up several 23-millimeter cannon hits, but the Soviet Shilka was fast to respond, lethally accurate, and could put more than "several" shells into a target in a burst -- the effect of its fire being compared to that of a buzzsaw. Tactical SAMs were also being improved. Could the Warthog realistically get down in the dirt with enemy forces and survive for long? If it couldn't, then that meant that the fast-mover strike aircraft that so exasperated the grunts in Vietnam were really the only game in town. The slogan went: "Speed is life."

As a result, the USAF began to look more towards the F-16 as the CAS solution. A four-barreled version of the GAU-8/A designated the "GAU-13/A" had been developed and configured into the "GPU-5/A Pave Claw" cannon pod. The cannon pod could be carried on the F-16's centerline pylon, and an F-16 with the Pave Claw and Mavericks seemed like it would be the right solution to the problem. 24 Air National Guard F-16s were eventually equipped with the Pave Claw. There was even talk of manufacturing an "A-16", an F-16 optimized for the CAS role, carrying the Pave Claw pod and fitted with additional armor.

What about the Warthogs? With the collapse of the Soviet Bloc in the late 1980s, the hordes of Red armor that threatened Europe were clearly not going to materialize, which meant the main threat the A-10 was supposed to deal with had evaporated. In principle the F-16 could do the CAS job; there seemed to be no real need for the Hog any longer, and the plan was to gradually phase it out.

As long as A-10s were in the inventory, of course they might as well be put to use, so the Air Force decided to "re-mission" them into the "forward air control (FAC)" role, with the new designation of "OA-10A". An OA-10A was exactly the same as an A-10A, the only real difference being that the OA-10A's normal payload was packs of 70-millimeter (2.75-inch) folding fin rockets with phosphorus warheads for target marking. The OA-10A designation was generally regarded as strictly a paperwork gimmick and never really caught on.

BACK_TO_TOP* And then, in 1990, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The US built up forces in Saudi Arabia under Operation DESERT SHIELD, with 194 A-10s deployed to the theater. When Saddam Hussein rejected ultimatums to withdraw from Kuwait, Iraqi forces were evicted under a lightning campaign, Operation DESERT STORM, that jumped off on 16 January 1991.

The Hog proved a very useful element in the air war, conducting 8,755 sorties, with a very high availability and weapons delivery rate; over 5,000 Mavericks were fired. A-10 pilots were in the air about eight hours a day, sometimes longer. Hogs claimed the destruction of hundreds of trucks, tanks, artillery pieces, and other targets. They even scored two air-to-air kills, with Hogs using cannon fire to shoot down an Iraqi helicopter on 6 February and 15 February. They also served in the FAC role, spotting targets for other "shooters".

Five A-10s were lost, with two pilots killed, but others took a beating and kept on flying. On 15 February, Captain Paul Johnson's Hog had a 9-meter (20-foot) long gouge torn out of its wing by a man-portable SAM, but the aircraft made it back to base. Another had most of its right rudder blown off and kept on flying. Observers noticed how projectiles simply glanced off the titanium bathtub around the cockpit. During a futile Iraqi counteroffensive on 25 February, two Hogs flew three sorties each and claimed the destruction of 23 tanks, with damage to ten others.

Iraqi troops greatly feared the A-10, reportedly calling it the "Circling Buzzard" as it idled ominously overhead for hours in a nerve-wracking fashion, hunting for something to kill, pouring out fire when it did and shrugging off hits. Coming in very silently, the first time many Iraqis knew they were under attack by Hogs was when the fire started pouring in. There were reports of Iraqi tankers simply bailing out of their armor and running for it when Hogs showed up. A-10s also served in the "Sandy" role, flying top cover for rescue of downed aircrew.

A-10s in the combat theater retained their Charcoal Lizard green-gray color scheme, though it wasn't very effective camouflage in the desert. Aircrews did dress up the machines with flashy nose art, the usual prerogative of frontline combatants. Although the A-10 wasn't intended for night combat, pilots did it anyway, using the infrared seekers on their Maverick missiles to see in the dark, and dropping illumination flares when they needed to. The "Nighthogs" inflicted punishment on the enemy, and came back without a scratch.

* In the end, in its first combat service the Warthog had generally validated all the careful thinking that went into its design. As in Vietnam, the ground-pounders didn't want a fast-mover coming in to hit and then run off, they wanted a real "mudfighter" that could hang around the battlefield, both dishing it out and taking it, for as long as was necessary. The F-16 also simply could not tolerate the ground fire at low altitude anywhere near as well as the Hog. To some, this was not at all a surprise. One retired Pentagon engineer was cited in THE WALL STREET JOURNAL as saying that the notion of using the F-16 for CAS was "one of the most monumentally fraudulent ideas the Air Force has ever perpetrated."

The Air Force finally accepted reality and eliminated plans to phase out the A-10, though the size of the fleet was trimmed back considerably as a reflection on the post-Cold-War environment. The Air Force had fought very hard with the Army during the Vietnam War to establish that the USAF, not the Army, owned the fixed-wing CAS mission. Insisting that the Army could not perform that task, while refusing to do a satisfactory job of it for them, would create endless dispute and, eventually, an intervention by irritated higher authorities that neither of the services wanted, being bad for the careers of the officers involved.

The A-10 continued to fight during the 1990s, operating in enforcement of the cease-fire stipulations imposed on the Iraqis and in US interventions in the Balkans during the Wars of the Yugoslav Succession. By that time, most of the conflicts envisioned US air superiority, making the main threat against the Hog SAMs instead of fighters. As a result, the A-10 fleet went to an overall gray color scheme.

* One of the controversies created by the A-10 over its long career was its use of depleted-uranium ammunition. There were concerns after the Gulf War that DU ammunition might be a contributing factor to the mysterious malady known as "Gulf War Syndrome" that afflicted some troops, and certainly its nature as decayed radioactive material did invite some suspicion.

However, after the fighting in the Balkans, a United Nations Environmental Program team went into areas that had been heavily carpeted by DU ammunition from the A-10 and other platforms to determine the effect it might have on the environment. As it turned out, it was almost impossible to pick out the contribution of DU ammunition from the natural background radiation of the environment, and in fact the major contribution to the background was from the fallout from the nuclear reactor accident at Chernobyl in Ukraine in 1987, over ten years before.

There was a possibility that DU ammunition might enhance heavy-metal pollution in the environment -- but in this regard, it was not different from conventional lead ammunition. The DU ammunition controversy has since moved to the fringes.

BACK_TO_TOP* The A-10 kept on going into the 21st century. It fought in Afghanistan following the occupation of the country in 2001, often cooperating with Lockheed Martin AC-130 gunships, which provided more sensor capability. During the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Hog provided its usual heavy fire support, and once again demonstrated its ability to soak up punishment as well as dish it out. Captain Kim Campbell, a woman pilot, managed to get a chewed-up A-10 back to base even after it had lost all its hydraulics, and Major Gary Wolf similarly returned home after a man-portable SAM completely destroyed one engine.

The A-10 received upgrades that no doubt made Hog pilots very happy. Just before the Gulf War, the Air Force had begun a program designated "Low Altitude Safety & Targeting Enhancement (LASTE)", which involved fitting the aircraft with a navigation-attack system derived from that used on the Vought A-7 strike fighter, linked to the A-10's SAS. LASTE provided precision aiming for ordnance and the GAU-8 cannon, turning targeting that had previously been an art into a science, and permitting attacks from high altitude. All the pilot had to do was place an indicator over the target on the cockpit HUD during an attack run, and then LASTE would give the nod on when to release or fire. LASTE even permitted cannon attacks from 4,575 meters (15,000 feet) slant range, an unbelievable capability to old-timers, and could keep the cannon on target while firing.

LASTE also provided a much-appreciated autopilot and a "ground collision avoidance system (GCAS)" that used inputs from a radar altimeter to give warning when the pilot was too low, with a shrieking voice screaming for the pilot to pull up. In addition, night vision goggle (NVG) capability was provided after the Gulf War.

In 2000, the A-10 was, finally, qualified to carry the Rafael / Northrop Grumman Litening 2 targeting pod. This pod includes a visible-light CCD TV camera with zoom capabilities, a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera, a laser target designator, and a laser rangefinder and spot tracker. The LANTIRN came in handy during the Afghan campaign in the winter of 2001:2002 and in the Iraq campaign in the spring of 2003, being used not only to target laser-guided bombs, but to perform spotting and bomb-damage assessment.

The Air Force followed up the Litening 2 pod integration effort with a more extensive upgrade, named "Precision Engagement (PE)". The original Litening pod fit simply used the old Maverick targeting display and provided very limited functionality. PE provided a much more comprehensive cockpit and avionics systems upgrade, including:

The updated machine was designated the "A-10C". Lockheed Martin performed the initial upgrades, and then provided kits to the USAF for installation at Hill AFB in Ogden, Utah. The first machine to be upgraded performed its initial flight in the new configuration in early 2005, to be used for qualifications and trials. The A-10C was formally rolled out by the Air Force in late 2006.

That wasn't the end of updating the A-10 by any means. The A-10 put in extensive service in the war in Afghanistan, which led to a lot of wear and tear on the aircraft, particularly the wings. A re-winging effort was begun by Boeing in 2007, with the first re-winged machine handed back for service in 2012. 242 wing sets were to be produced, but only 173 were initially funded, with the last re-winged A-10 returned to service in 2019. A follow-on project was initiated to provide the remainder of the wing sets.

The war in Afghanistan also demonstrated that the "hot & high" performance of the TF34-100A engines left something to be desired, and so there was thought of refurbishing and modernizing the engines to TF34-100B specification, with a new fan and new components rated for higher operating temperatures. The updated engines would give the A-10C much improved performance. However, it hasn't happened yet.

Efforts to sustain the Warthog fleet were conducted in the face of doubts about the Warthog's future. The size of the A-10 fleet was cut to 283 machines, that being seen as enough to support the mission; with the Air Force then proposing to retire the fleet completely as soon as possible. The result of such talk was a wild controversy. The Air Force, suffering from a budget pinch, believed the A-10 was becoming ever less survivable in the modern battlefield environment. CAS boosters had heard the notion of replacing the A-10 with a less optimized aircraft before, and were skeptical. Congress was also not sympathetic to retiring the A-10.

In the face of the controversy, in early 2016 Defense Secretary Ashton Carter announced that the A-10 would not be completely retired before 2022, Carter describing the Warthog's effect against Islamic State (IS) insurgents as "devastating". However, following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in the summer of 2021, the A-10 was more or less out of a job, with the Air Force pressing again for its retirement. After Ukraine was invaded by Russia in early 2022, the Ukrainians tried to request retired A-10s, to be told they were simply too vulnerable. They were; the Russians had a layered air defense system, and Ukrainian aircraft venturing over Russian lines had an unfortunate tendency to be shot down.

Nonetheless, the Warthog has been receiving and is still receiving further updates, including:

The package of advanced upgrades was called the "Common Fleet Initiative" or informally "Super Warthog / A-10C II". One of the most significant features of the Super Warthog was support of new munitions:

These munitions demonstrated that the A-10's mission has been rethought in its declining years, de-emphasizing the battlefield CAS mission. The SDB is a stand-off weapon; an A-10 can send them gliding to targets tens of kilometers away, remaining out of the reach of adversary air defenses. MALD isn't even a battlefield weapon. The push is to squeeze some last usefulness out of the Warthog. It will probably remain in service to 2030, but who knows how much longer than that? Having been in service for like half a century, it would hardly be retired before its time.

BACK_TO_TOP* Although potential foreign users weren't that impressed with the Hog, the Soviets were interested enough to build their own counterpart, the Sukhoi Su-25 Grach (Rook), known to NATO as the "Frogfoot". In one sense, this was unsurprising, since the Soviets had been enthusiastic users of the Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmoviks during World War II, and this aircraft was conceptually very much like the Hog, being a heavily armored and armed aircraft intended for low-level battlefield support. The USSR was a pioneer of this type of machine.

After the war the Soviets lost interest in the concept and, like the US, relied on conventional fighter aircraft for the close-support role. Work on the Su-25 was provoked by the US AX competition. The Soviets were in a hurry, however, and the end result was clearly inferior to the A-10 in a number of respects. It carried a substantially smaller warload; used thirsty turbojets that limited its battlefield endurance; and carried a twin-barreled "teeter-totter" GSh-30 30-millimeter cannon, less potent for the antitank role than the GAU-8/A. Incidentally, the Soviets did develop a six-barreled 30-millimeter cannon along the lines of the GAU-8A, the GSh-6-30, for the MiG-27 attack aircraft -- but by all reports it was a disaster, so prone to dangerous malfunctions that pilots didn't like to fire it, and the shock generally broke all the aircraft's landing lights.

The Su-25's configuration was generally similar to that of the Northrop YA-9A, with the engines under the wing roots, which made them more vulnerable to battle damage than the pod-mounted TF34s of the A-10, and in general the Su-25 was not as well thought out as the A-10 in terms of survivability. Sukhoi engineers were aware that the A-10's engine layout was superior and wanted to implement it on the Su-25, but it was too late in the development cycle to change.

All that being said, the Su-25 proved a very capable aircraft that acquitted itself well in Afghanistan. It was agile and rugged -- its Tumanskiy turbojets might not have been highly fuel-efficient, but they were specifically built for combat reliability, and they provided better acceleration than the A-10's turbofans -- and no Afghan mujahedin warriors who had to endure its firepower would have argued that it was poorly armed. Certainly a Hog rarely actually carried its maximum rated external warload. The Frogfoot was likely cheaper to build -- though it might be difficult to unravel the actual costs given the peculiarities of finances in the Soviet system, or for that matter the arcane accounting practices sometimes applied to weapon systems everywhere -- and it is hard to say the Soviets got a poorer deal.

Indeed, when the Ukrainians asked to be given A-10s, the response was likely that they had Su-25s -- why did they think the A-10 was so much better a deal? To be sure, an A-10 could carry much more advanced armament, such as SDBs, but there was a push by Ukraine's allies to adapt Ukraine's old Soviet combat aircraft to carry modern Western munitions. We don't know yet what munitions the Frogfoot was modified to carry for Ukraine, but we're likely to get surprises.

BACK_TO_TOP* There is a story that I ran across a long time ago that in the course of the A-10's development, some of the people involved actually talked to Hans-Ulrich Rudel, Germany's greatest CAS "ace" and a prominent mountain-climber. He came to Ohio, staying at a farm near Wright-Patterson AFB, where there were discreet conversations with him. His war memoirs STUKA PILOT were a classic, documenting how his skills had allowed him to rack up massive scores against Red Army tanks and other targets on the Eastern Front during World War II.

There was nobody in the world who knew more about the theory and practice of CAS and tank-busting, and his advice was given considerable weight. The talks were kept very quiet. The US had adopted Dr. Wernher von Braun, who had led the team that developed the infamous German V-2 long-range missile of World War II, to become one of the driving wheels behind the Apollo Moon program. Von Braun had become a face known to every American in the 1960s, but he had still been controversial. Worse, Rudel was an unrepentant Nazi. Rudel had never been seriously accused of war crimes, but there was no reason to invite trouble by publicizing that he had been used as a consultant on an American defense program.

Another interesting footnote to the A-10 story is that in 2011 the US National Science Foundation (NSF) managed to get their hands on an A-10 for use in weather research; given its strength, it was an ideal platform for use as a "storm chaser" -- the engines can swallow oversized hailstones and keep on turning. The actual operator on behalf of the NSF was to be the Navy Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, making the US Navy a Warthog operator of sorts. The Navy converted the A-10 to its new configuration, removing the GAU-8A cannon to make space for instruments; instruments were also to be carried on the stores pylons. Alas, the project went out of control, and was abandoned in 2019.

* I was surprised when I did this writeup that it went to such length and detail. I was expecting to write something maybe a third as long. However, it turns out that the A-10 is such a unique aircraft that it is full of little surprises, and a brief description simply does not do it justice.

* Sources include:

* Illustration credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 oct 08 v1.0.1 / 01 may 10 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 mar 12 / NSF A-10 for weather science. v1.0.3 / 01 feb 14 / Review & polish. v1.0.4 / 01 jan 16 / Review & polish. v1.0.5 / 01 dec 17 / Review & polish. v1.0.6 / 01 nov 19 / Review & polish. v1.1.0 / 01 oct 21 / Illustrations update, some rewrite. v1.2.0 / 01 sep 23 / Review, update, & polish.BACK_TO_TOP